The Industrial Revolution Reader

advertisement

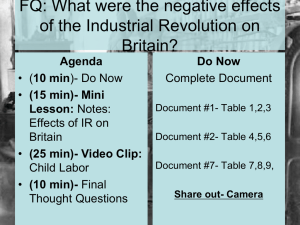

1 The Industrial Revolution Words you should look up and understand before reading the excerpts. Write the definition here: Industrial Revolution Urbanization Commodities The term "Industrial Revolution" is thought to have originated among French commentators at the turn of the 19th century. Those authors suggested that many nations were experiencing changes that were resulting in profound economic and social transformations. Indeed, the Industrial Revolution, which had its beginnings in remote times but is generally deemed to have taken place from the late 18th to early 19th centuries, marked the onset of industrial society and defined the key mechanisms of its progress. Although the pace of industrial development obviously differed between nations, there were many similarities. The Industrial Revolution encompassed a number of components, including technological advances. Economic growth, the subsequent development of new markets, changes in the transportation of goods, improved communications, and changes in the social structure were also important factors. All of those factors were evident in England, which is often credited with playing a leading role in the Industrial Revolution. Although a predominantly agricultural society, at the beginning of the 18th century, England was already an important industrial producer. Best known for the manufacture of woolen cloth, England also produced great quantities of tin, coal, leather goods, small metal goods, and other domestic items. Moreover, there were many technological advances in England during the 18th century. Some were of benefit to many different types of industries. These included James Watt's steam engine, which could either replace or supplement power from traditional sources like watermills and windmills. Initially, the steam engine was developed for use in the mining industry to provide greater amounts of coal. It was later adapted to power different types of machinery within factories. Other inventions aided specific industries, like the production of cloth. They included the flying shuttle, which was patented in 1733 by a Lancashire mechanic named John Kay. Previously, four spinners were needed to keep up with a single cotton loom. Ten additional people were needed to prepare yarn for one woolen weaver. The new shuttle expedited this process by allowing the yarn to be produced more quickly. Richard Arkwright's water frame, patented in 1769, further accelerated the production of yarn. Less then a decade later, Samuel Crompton combined those two machines into what became known as Crompton's mule. 2 Economic growth was also readily apparent in 18th-century England. The country already enjoyed a vigorous export trade to Europe, the American colonies, India, and Africa. Further growth in international trade was fueled by political developments across Europe. After 1713, the British were allowed to trade with the Spanish Empire in South and Central America. New markets were created by the growth of English colonies in the West Indies and India. As the pace of industrialization increased, a growing number of cheap manufactured goods were sent to the colonies. Those goods included articles ranging from hammers, shovels, and anchors to firearms and gunpowder. Although ships were used for long-distance trade, other forms of transportation developed to deal with internal European trade. Navigable rivers had long played a role in the distribution of both raw and manufactured goods. Those natural channels were supplemented in the second half of the 18th century by the construction of a canal system. Roads also continued to improve thanks in part to the growth of turnpike roads, which charged a toll for their use and subsequent upkeep. During the 19th century, the development of railroads changed the face of transportation forever. By 1850, trains were able to travel between 30 and 50 miles an hour to speed both raw materials and consumer goods across Europe. Improved methods of communication were another factor in the acceleration of industrialization. Sir Samuel Cunard pioneered the concept of transatlantic mail in 1839. After gaining permission from the British government, he began a postal system between Liverpool, Halifax, and Boston. In 1840, a new method of sending mail was implemented in England. The new penny post was based on the concept that it was the handling, rather than the distance sent, that was the critical cost in delivering mail. By the third quarter of the 19th century, telegraph cables enabled businesses to communicate to far-away lands. This period also saw the development of the Universal Postal Union, whose purpose was to facilitate the movement of post overseas. A final major factor in the European Industrial Revolution was that of changes in the social structure. Those changes included a dramatic increase in population and urbanization that was most apparent in England and Germany. By the mid-19th century, only half of the English population still dwelled in rural areas. Over the following 50 years, the same became true for many European countries. Growing urbanization was caused by three main requirements of industrial growth. First of all, most factories were located in centers where coal or other raw materials were available, like the Ruhr Valley in Germany. Second, cities were normally located in centers of transportation, like Liverpool and Marseille. Finally, banks and other forms of commerce were generally established in political centers like London, Paris, and Berlin. Many of the immigrants to urban areas were part of what became a new working class. Factories called for a large number of workers to run machinery. In many cases, the factory owners tended to consider their employees as little more than commodities. The men, women, and children who filled those roles were generally subjected to long hours, low wages, and poor working conditions. Artisans, who had previously been considered to be skilled workers, also found themselves degraded to routine laborers. The Industrial Revolution also helped in the creation of a middle class. New occupations were developed in order to cope with the running of factories. 3 Those occupations included managers, engineers, and skilled workers like mechanics and toolmakers. Industrialization in England also affected the growth of its colonies. During the early 18th century, the British colonies were concerned with the need to make a living rather than industrial advancement. The Industrial Revolution changed that attitude by increasing the demand for colonial goods, which enjoyed a protected market. In addition, industrialization supplied capital to the colonists. However, the Industrial Revolution in the United States followed a different, somewhat later course. Although agriculture was the main source of income, there were major differences in the way business developed in the South and North. Tobacco, which was grown in the former areas, was probably the most important export. Tobacco was a very successful product and was supplied in increasing quantities to England and France. There was also a growing timber industry, developed through the use of traditional water-powered sawmills. While the southern part of the country concentrated on cash crops, the North had a growing commercial sector and showed the beginnings of manufacturing. The successful export of a range of foodstuffs and timber resulted in the demand for new ships. In addition to shipbuilding, the northern colonies also became known for the smelting of iron and production of metal wares. By the second half of the 18th century, colonial iron output was sufficiently high for the British Parliament to pass an act controlling the industry. By 1760, a number of factories had also opened to produce pottery, glass, cloth, and paper. Industrialization accelerated in the early 19th century with the growth of the young American nation. Consumer and industrial demand led to a rising number of factories. In 1814, Francis Cabot Lowell began the first large-scale mechanized American mill for the production of textiles. Other successful new businesses included the manufacture in the mid-19th century of armaments. Samuel Colt's range of pistols was made with the best precision machine tools available at that time. The growing industrialization of the United States also had an impact on agriculture. Cyrus McCormick was responsible for one of the most important tools for the nation's farmers. He invented the reaper, a piece of machinery that replaced the labor-intensive hand sickles that had traditionally been used for cutting grain. By using a horse-drawn reaper, the time needed to harvest a field that previously took 20 hours was reduced to one hour. Although initially produced on a small scale, the demand for the machines quickly grew. In response, the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company was founded in 1847 to supply enough reapers for the entire country. The last half of the 19th century experienced another set of technological innovations. Those included the development of cheap steel, which allowed factory machinery to be produced more quickly. As companies continued to expand, many merged with each other to create large and powerful corporations. By the end of the century, those mergers resulted in a large number of highly integrated, conglomerate corporations both in the United States and in Europe. 4 However, while the Industrial Revolution had been portrayed in the middle of the 19th century as one of humankind's greatest achievements, to many 20th-century critics, that was no longer the case. Social reformers noted the moral and spiritual deficiencies of an industrialized society, including the disparity between the wealthy industrialists and the urban working class. Nevertheless, the so-called revolution continued during the 20th century, and industrialization spread throughout the world. CITATION: MLA STYLE "Industrial Revolution." World History: The Modern Era. ABC-CLIO, 2009. Web. 29 Sept. 2009. <http://www.worldhistory.abc-clio.com>. 5 The Industrial Revolution Timeline, 1700-early 1900s 1698 English engineer Thomas Savery developed a steam engine. He successfully advertised his water pumping steam engine to owners of coal mines in his region of England where deepening mines kept filling with water. 1700 2.7 million tons of coal were mined in Britain. 1750 4.7 million tons of coal were mined in Britain. 1769 2,500 steam engines were being used to pump water out of coal mines in Britain. 1797 900 cotton mills were operating across Britain. 1800 10 million tons of coal were mined in Britain. 1814 Francis Cabot Lowell begins the first large-scale mechanized U.S. mill for the production of textiles (fabric). 1818 The Industrial Revolution leads to growing international concerns with alcoholism, starting the temperance movement (to make alcohol illegal). The earliest recorded temperance group in Europe is established in Sweden. 1819 On August 16, in what is known as the Peterloo massacre, the British cavalry clears out a crowd of tens of thousands of British people gathered peacefully to protest a year of industrial depression and high food prices in the hope of initiating parliamentary reform. In response to the incident, the British Parliament pass the Six Acts, a limit on civil liberties in Great Britain that includes the prohibition of a gathering of more than 50 people. 1820 34 steam-powered ships operated in British waters. 1830 A few dozen miles of railroad track existed in Britain. 6 1833 The British Parliament enacts the Factory Act (1833), the first significant legislation passed anywhere in the world to attempt to deal with the appalling conditions faced by workers laboring in factories. 1838 William Lovett and Francis Place write the Chartist People's petition (1838), a mandate for reform of the British government's policies regarding workplace conditions. 1840 Britain was exporting 200 million yards of cotton textiles to other European countries and 529 million yards of cotton textiles elsewhere in the world. 1840 4,500 miles of railroad track existed in Britain. 1845 The Irish potato famine begins, bringing high unemployment, overcrowding in populated areas, and general poverty. 1848 Karl Marx publishes the Communist Manifesto (1848). 1848 French workers revolt in the June Days after losing hope in the economic and social reforms promised by the government during the uprisings earlier that year. 1848 The Seneca Falls Convention is held from July 19 to July 20. Organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth and Mary Ann McClintock, the convention is the first women's rights convention in U.S. history. 1850 50 million tons of coal were mined in Britain. 1850 23,000 miles of railroad track existed in Britain. 1854 The Irish potato famine ends after tens of thousands of people have died of outright starvation. An estimated 1.1 million people have died of famine-related diseases, and another 1.5 million Irish have fled their homeland in search of a new sense of security and a better chance for survival. 1862 Andrew Carnegie forms the Piper and Shiffler Company to make iron railroad bridges. 7 1864 The first international association to fight for the rights of workers, the First International (also called the International Workingmen’s Association) is organized. 1865 John D. Rockefeller creates the firm of Rockefeller & Andrews, Cleveland, Ohio's largest oil refiner. 1869 The golden spike ceremony marks the completion of the transcontinental railroad in the United States. 1869 In the United States, women fight for the right to vote. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony form the National Woman Suffrage Association. Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, and Henry Ward Beecher lead the American Woman Suffrage Association. 1875 Andrew Carnegie founds the Carnegie Steel Company. 1875 Alexander Graham Bell makes the first true communication by telephone. 1890 Jacob Riis publishes his first and most famous book, How the Other Half Lives. Its photographs and accompanying text show the horrible living conditions of the poor in New York City. 1903 Henry Ford founds Ford Motor Company in Dearborn, Michigan. 1906 Upton Sinclair publishes The Jungle (1906), a scathing exposé regarding sanitation practices in the meat-packing industry and the brutal condition of the workers' lives who labor in that industry. 1908 Ford Motor Company introduces the Model T, using the assembly line for production. 8 Industrial Revolution Primary Source “Lowell Mill Girls” by Harriet Robinson, 1883 Description of Source: In her autobiography, Harriet Hanson Robinson, the wife of a newspaper editor, provided an account of her earlier life as female factory worker (from the age of ten in 1834 to 1848) in the textile Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts. Her account explains some of the family dynamics involved, and lets us see the women as active participants in their own lives for instance in their strike of 1836. Primary Source Excerpts: In what follows, I shall confine myself to a description of factory life in Lowell, Massachusetts, from 1832 to 1848, since, with that phase of Early Factory Labor in New England, I am the most familiar-because I was a part of it. In 1832, Lowell was little more than a factory village. Five "corporations" were started, and the cotton mills belonging to them were building. Help was in great demand and stories were told all over the country of the new factory place, and the high wages that were offered to all classes of workpeople; stories that reached the ears of mechanics' and farmers' sons and gave new life to lonely and dependent women in distant towns and farmhouses .... Troops of young girls came from different parts of New England, and from Canada, and men were employed to collect them at so much a head, and deliver them at the factories. ... At the time the Lowell cotton mills were started the caste of the factory girl was the lowest among the employments of women. In England and in France, particularly, great injustice had been done to her real character. She was represented as subjected to influences that must destroy her purity and self-respect. In the eyes of her overseer she was but a brute, a slave, to be beaten, pinched and pushed about. It was to overcome this prejudice that such high wages had been offered to women that they might be induced to become mill girls, in spite of the opprobrium that still clung to this degrading occupation.... The early mill girls were of different ages. Some were not over ten years old; a few were in middle life, but the majority were between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five. The very young girls were called "doffers." They "doffed," or took off, the full bobbins from the spinning frames, and replaced them with empty ones. These mites worked about fifteen minutes every hour and the rest of the time was their own. When the overseer was kind they were allowed to read, knit, or go outside the mill yard to play. They were paid two dollars a week. The working hours of all the girls extended from five o'clock in the morning until seven in the evening, with one half-hour each, for breakfast and dinner. Even the doffers were forced to be on duty nearly fourteen hours a day. This was the greatest hardship in the lives of these children. Several years later a ten-hour law was passed, but not until long after some of these little doffers were old enough to appear 9 before the legislative committee on the subject, and plead, by their presence, for a reduction of the hours of labor. Those of the mill girls who had homes generally worked from eight to ten months in the year; the rest of the time was spent with parents or friends. A few taught school during the summer months. Their life in the factory was made pleasant to them. In those days there was no need of advocating the doctrine of the proper relation between employer and employed. Help was too valuable to be ill-treated.... ... The most prevailing incentive to labor was to secure the means of education for some male member of the family. To make a gentleman of a brother or a son, to give him a college education, was the dominant thought in the minds of a great many of the better class of mill girls. I have known more than one to give every cent of her wages, month after month, to her brother, that he might get the education necessary to enter some profession. I have known a mother to work years in this way for her boy. I have known women to educate young men by their earnings, who were not sons or relatives. There are many men now living who were helped to an education by the wages of the early mill girls. It is well to digress here a little, and speak of the influence the possession of money had on the characters of some of these women. We can hardly realize what a change the cotton factory made in the status of the working women. Hitherto woman had always been a money saving rather than a money earning, member of the community. Her labor could command but small return. If she worked out as servant, or "help," her wages were from 50 cents to $1 .00 a week; or, if she went from house to house by the day to spin and weave, or do tailoress work, she could get but 75 cents a week and her meals. As teacher, her services were not in demand, and the arts, the professions, and even the trades and industries, were nearly all closed to her. As late as 1840 there were only seven vocations outside the home into which the women of New England had entered. At this time woman had no property rights. A widow could be left without her share of her husband's (or the family) property, an " incumbrance" to his estate. A father could make his will without reference to his daughter's share of the inheritance. He usually left her a home on the farm as long as she remained single. A woman was not supposed to be capable of spending her own, or of using other people's money. In Massachusetts, before 1840, a woman could not, legally, be treasurer of her own sewing society, unless some man was responsible for her. The law took no cognizance of woman as a moneyspender. She was a ward, an appendage, a relict. Thus it happened that if a woman did not choose to marry, or, when left a widow, to remarry, she had no choice but to enter one of the few employments open to her, or to become a burden on the charity of some relative. ... One of the first strikes that ever took place in this country was in Lowell in 1836. When it was announced that the wages were to be cut down, great indignation was felt, and it was decided to strike or "turn out" en masse. This was done. The mills were shut down, and the girls went from 10 their several corporations in procession to the grove on Chapel Hill, and listened to incendiary speeches from some early labor reformers. One of the girls stood on a pump and gave vent to the feelings of her companions in a neat speech, declaring that it was their duty to resist all attempts at cutting down the wages. This was the first time a woman had spoken in public in Lowell, and the event caused surprise and consternation among her audience It is hardly necessary to say that, so far as practical results are concerned, this strike did no good. The corporation would not come to terms. The girls were soon tired of holding out, and they went back to their work at the reduced rate of wages. The ill success of this early attempt at resistance on the part of the wage element seems to have made a precedent for the issue of many succeeding strikes. Citation: Robinson, Harriet H. "Early Factory Labor in New England," in Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, Fourteenth Annual Report (Boston: Wright & Potter, 1883), pp. 38082, 38788, 39192. 11 Industrial Revolution Primary Source Women Miners in the English Coal Pits, 1842 Description of Source: The following is a written observation of the work being done in coal mines during the Industrial Revolution. Primary Source Excerpts: In England… female Children of tender age and young and adult women are allowed to descend into the coal mines and regularly to perform the same kinds of underground work, and to work for the same number of hours, as boys and men… In great numbers of the coalpits in this district the men work in a state of perfect nakedness, and are in this state assisted in their labour by females of all ages, from girls of six years old to women of twenty-one, these females being themselves quite naked down to the waist… One of the most disgusting sights 1 have ever seen was that of young females, dressed like boys in trousers, crawling on all fours, with belts round their waists… When I arrived at the board or workings of the pit I found at one of the sideboards down a narrow passage a girl of fourteen years of age in boy's clothes, picking down the coal with the regular pick used by the men. She was half sitting half lying at her work, and said she found it tired her very much, and 'of course she didn't like it.' The place where she was at work was not 2 feet high. Further on were men lying on their sides and getting. No less than six girls out of eighteen men and children are employed in this pit… In two other pits in the Huddersfield Union I have seen the same sight. In one near New Mills, the chain, passing high up between the legs of two of these girls, had worn large holes in their trousers; and any sight more disgustingly indecent or revolting can scarcely be imagined than these girls at work-no brothel can beat it… When it is remembered that these girls hurry chiefly for men who are not their parents; that they go from 15 to 20 times a day into a dark chamber (the bank face), which is often 50 yards apart from any one, to a man working naked, or next to naked, it is not to be supposed but that where opportunity thus prevails sexual vices are of common occurrence… Citation: Great Britain, Parliamentary Papers, 1842, VoL XVI, pp. 24, 196. 12 Description of Source: The following is an oral account from a woman who worked in the mines. Primary Source Excerpts Betty Harris, age 37: I was married at 23, and went into a colliery when I was married. I used to weave when about 12 years old; can neither read nor write. I work for Andrew Knowles, of Little Bolton (Lancs), and make sometimes 7s a week, sometimes not so much. I am a drawer, and work from 6 in the morning to 6 at night. Stop about an hour at noon to eat my dinner; have bread and butter for dinner; I get no drink. I have two children, but they are too young to work. I worked at drawing when I was in the family way. I know a woman who has gone home and washed herself, taken to her bed, delivered of a child, and gone to work again under the week. I have a belt round my waist, and a chain passing between my legs, and I go on my hands and feet. The road is very steep, and we have to hold by a rope; and when there is no rope, by anything we can catch hold of. There are six women and about six boys and girls in the pit I work in; it is very hard work for a woman. The pit is very wet where I work, and the water comes over our clog-tops always, and I have seen it up to my thighs; it rains in at the roof terribly. My clothes are wet through almost all day long. I never was ill in my life, but when I was lying in. My cousin looks after my children in the day time. I am very tired when I get home at night; I fall asleep sometimes before I get washed. I am not so strong as I was, and cannot stand my work so well as I used to. I have drawn till I have bathe skin off me; the belt and chain is worse when we are in the family way. My feller (husband) has beaten me many a times for not being ready. I were not used to it at first, and he had little patience. I have known many a man beat his drawer. I have known men take liberties with the drawers, and some of the women have bastards. Citation: Great Britain, Parliamentary Papers, 1842, Vol. XV, p. 84, and ibid., Vol. XVII, p. 108. 13 Industrial Revolution Primary Source Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844 by Friederich Engels, 1844 Description of Source: Manchester, England rapidly rose from obscurity to become the premier center of cotton manufacture in England. This was largely due to geography. Its famously damp climate was better for cotton manufacture than the drier climate of the older eastern English cloth manufacture centers. As a result, Manchester became perhaps the first modern industrial city. Friedrich Engels' father was a German manufacturer and Engels worked as his agent in his father's Manchester factory. As a result he combined both real experience of the city, with a strong social conscience. The result was The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844. He also went on to write the Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx, which was published in 1848. Primary Source Excerpts: The following is a description of Manchester, England: Describing courtyards (public spaces) in the city: In one of these courts there stands directly at the entrance, at the end of the covered passage, a privy without a door, so dirty that the inhabitants can pass into and out of the court only by passing through foul pools of stagnant urine and excrement. . . . Here, as in most of the working-men's quarters of Manchester, the pork-raisers rent the courts and build pig-pens in them. In almost every court one or even several such pens may be found, into which the inhabitants of the court throw all refuse and offal, whence the swine grow fat; and the atmosphere, confined on all four sides, is utterly corrupted by putrefying animal and vegetable substances.... Describing a river in the city: At the bottom flows, or rather stagnates, the Irk, a narrow, coal-black, foul-smelling stream, full of debris and refuse, which it deposits on the shallower right bank. In dry weather, a long string of the most disgusting, blackish-green, slime pools are left standing on this bank, from the depths of which bubbles of miasmatic gas constantly arise and give forth a stench unendurable even on the bridge forty or fifty feet above the surface of the stream. But besides this, the stream itself is checked every few paces by high weirs, behind which slime and refuse accumulate and rot in thick masses. Above the bridge are tanneries, bone mills, and gasworks, from which all drains and refuse find their way into the Irk, which receives further the contents of all the neighbouring sewers and privies. It may be easily imagined, therefore, what 14 sort of residue the stream deposits. Below the bridge you look upon the piles of debris, the refuse, filth, and offal from the courts on the steep left bank; here each house is packed close behind its neighbour and a piece of each is visible, all black, smoky, crumbling, ancient, with broken panes and window frames. The background is furnished by old barrack-like factory buildings. On the lower right bank stands a long row of houses and mills; the second house being a ruin without a roof, piled with debris; the third stands so low that the lowest floor is uninhabitable, and therefore without windows or doors. Here the background embraces the pauper burial-ground, the station of the Liverpool and Leeds railway, and, in the rear of this, the Workhouse, the "Poor-Law Bastille" of Manchester, which, like a citadel, looks threateningly down from behind its high walls and parapets on the hilltop, upon the working-people's quarter below. Such is the Old Town of Manchester, and on re-reading my description, I am forced to admit that instead of being exaggerated, it is far from black enough to convey a true impression of the filth, ruin, and uninhabitableness, the defiance of all considerations of cleanliness, ventilation, and health which characterise the construction of this single district, containing at least twenty to thirty thousand inhabitants. And such a district exists in the heart of the second city of England, the first manufacturing city of the world. If any one wishes to see in how little space a human being can move, how little air - and such air! - he can breathe, how little of civilisation he may share and yet live, it is only necessary to travel hither. True, this is the Old Town, and the people of Manchester emphasise the fact whenever any one mentions to them the frightful condition of this Hell upon Earth; but what does that prove? Everything which here arouses horror and indignation is of recent origin, belongs to the industrial epoch. Citation: Engels, Friedrich. The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844 (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1892), pp. 45, 48-53. 15 Industrial Revolution Primary Source “Report on Sanitary Conditions,” by Edwin Chadwick, 1842 Description of Source: Edwin Chadwick (1800-1890) had taken an active part in the reform of the Poor Law and in factory legislation before he became secretary to a commission investigating sanitary conditions and means of improving them. The Commission's report, of which the summary is given below, is the third of the great reports of this epoch. The following material comes from Report...from the Poor Law Commissioners on an Inquiry into the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain [online source]. London, 1842, pp. 369-372. Primary Source Excerpts: After as careful an examination of the evidence collected as I have been enabled to make, I beg leave to recapitulate the chief conclusions which that evidence appears to me to establish. First, as to the extent and operation of the evils which are the subject of this inquiry: — That the various forms of epidemic, endemic, and other disease caused, or aggravated, or propagated chiefly amongst the labouring classes by atmospheric impurities produced by decomposing animal and vegetable substances, by damp and filth, and close and overcrowded dwellings prevail amongst the population in every part of the kingdom, whether dwelling in separate houses, in rural villages, in small towns, in the larger towns — as they have been found to prevail in the lowest districts of the metropolis. Contaminated London drinking water containing various micro-organisms, refuse, and the like. 16 That the formation of all habits of cleanliness is obstructed by defective supplies of water. That the annual loss of life from filth and bad ventilation are greater than the loss from death or wounds in any wars in which the country has been engaged in modern times. That of the 43,000 cases of widowhood, and 112,000 cases of destitute orphanage relieved from the poor's rates in England and Wales alone, it appears that the greatest proportion of deaths of the heads of families occurred from the above specified and other removable causes; that their ages were under 45 years; that is to say, 13 years below the natural probabilities of life as shown by the experience of the whole population of Sweden. That the public loss from the premature deaths of the heads of families is greater than can be represented by any enumeration of the pecuniary burdens consequent upon their sickness and death. That these habits lead to the abandonment of all the conveniences and decencies of life, and especially lead to the overcrowding of their homes, which is destructive to the morality as well as the health of large classes of both sexes. That defective town cleansing fosters habits of the most abject degradation and tends to the demoralization of large numbers of human beings, who subsist by means of what they find amidst the noxious filth accumulated in neglected streets and bye-places. Secondly. As to the means by which the present sanitary condition of the labouring classes may be improved:-The primary and most important measures, and at the same time the most practicable, and within the recognized province of public administration, are drainage, the removal of all refuse of habitations, streets, and roads, and the improvement of the supplies of water. That for all these purposes, as well as for domestic use, better supplies of water are absolutely necessary. That appropriate scientific arrangements for public drainage would afford important facilities for private land-drainage, which is important for the health as well as sustenance of the labouring classes. That for the prevention of the disease occasioned by defective ventilation and other causes of impurity in places of work and other places where large numbers are assembled, and for the general promotion of the means necessary to prevent disease, that it would be good economy to appoint a district medical officer independent of private practice, and with the securities of special qualifications and responsibilities to initiate sanitary measures and reclaim the execution of the law. 17 And that the removal of noxious physical circumstances, and the promotion of civic, household, and personal cleanliness, are necessary to the improvement of the moral condition of the population; for that sound morality and refinement in manners and health are not long found coexistent with filthy habits amongst any class of the community. Citation: Chadwick, Edwin. Report...from the Poor Law Commissioners on an Inquiry into the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain [online source]. London, 1842, pp. 369372.