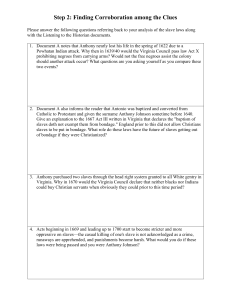

Author Study VIRGINIA HAMILTON Writer of Past and Present "The

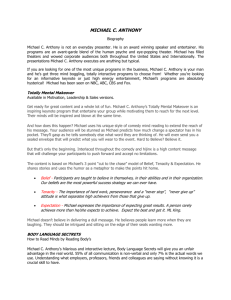

advertisement