Contextualism about Deontic Conditionals

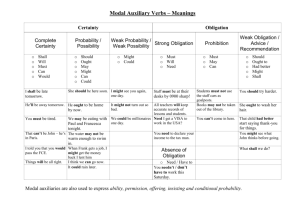

advertisement