Individual differences

advertisement

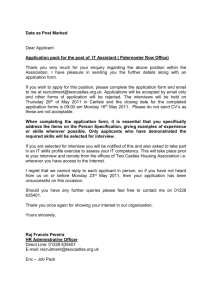

#16084 Running head: APPLICANT ATTRACTION Individual Differences in Applicant Attraction: The Role of Person-Organization Fit Kelly A. Piasentin and Derek S. Chapman University of Calgary 1 #16084 Abstract We investigated the extent to which individuals were attracted to organizational recruitment advertisements that emphasized supplementary fit (i.e., fitting in by being similar) or complementary fit (i.e., fitting in by adding unique characteristics), and whether there are individual difference traits that moderate these relationships. Using a within-subjects design, data from 128 participants revealed that individuals high in openness to experience and independent self-construal, as well as those with high needs for uniqueness, achievement, dominance, and autonomy all preferred advertisements that depicted complementary fit. Implications of these findings are discussed in terms of recruitment strategies aimed at promoting organizational diversity while selecting for person-organization fit. 2 #16084 3 Individual Differences in Applicant Attraction: The Role of Person-Organization Fit Understanding how to attract top applicants is becoming increasingly important for organizations. Economic uncertainty and demographic changes in today’s workforce, coupled with increasing challenges in finding qualified applicants (Michaels, Handfield-Jones, & Axelrod, 2001), have created a surge of attention being devoted to organizational recruitment. One area of interest has been research examining how job advertisements can influence potential applicants. Recruitment advertisements play a role in the applicant attraction stage of recruiting where the principle goal is to motivate applicants to apply for a position in a particular organization (Barber, 1998; Breaugh & Stark, 2001; Rynes, 1991). Accordingly, recruitment messages are typically designed to elicit favorable attitudes toward the organization. Previous research has focused on a number of variables of interest that are often presented in job advertisements. For example, information about pay, location, organizational values, job characteristics, and the work environment are but a few of the factors that have been studied and shown to influence applicants’ likelihood of applying for a job (for a detailed list, see the recent meta-analysis by Chapman, Uggerslev, Carroll, Piasentin, & Jones, in press). Of the various factors found to influence applicant attraction, person-organization (P-O) fit is thought to play a particularly critical role. P-O fit is generally defined as the extent to which individual characteristics (e.g., goals, values, and personality) are compatible with organizational characteristics (Kristof, 1996). Because employees with higher levels of P-O fit are found to have more positive work attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Cable & DeRue, 2002; Saks & Ashforth, 2002), recruiters are often advised to seek out individuals who have similar characteristics with existing organizational characteristics (Bretz & Judge, 1994; Bretz, Rynes, & Gerhart, 1993; Haptonstahl & Buckley, 2002). P-O fit is also found to be instrumental in #16084 4 shaping applicants’ attitudes and behaviors towards organizations, as individuals who perceive a good P-O fit with an organization are more likely to (a) be attracted to the organization, (b) pursue employment with the organization, and (c) accept a job offer from the organization (Cable & Judge, 1996; Dineen, Ash, & Noe, 2002; Judge & Cable, 1997; Lauver & KristofBrown, 2001; Turban, Lau, Ngo, Chow, & Si , 2001). Findings from a recent meta-analysis indicate that P-O fit is actually one of the most important predictors of attitudinal applicant attraction outcomes (Chapman et al., in press). Most of our knowledge about how P-O fit influences applicant attraction is based on the assumption that applicants seek out a supplementary fit with potential organizations; that is, individuals are thought to make judgments about the extent to which they fit into an organization based on how similar their characteristics are to organizational characteristics. It has been speculated, however, that P-O fit may also occur from complementarity between individual and organizational characteristics (Muchinsky & Monahan, 1987); in other words, individuals may fit into an organization by possessing unique characteristics that add to, or complement, the organization’s characteristics. In the context of recruiting, there are several important reasons why some employers might want to focus on complementary fit rather than supplementary fit. First, as Schneider (1987) warned, the attraction of individuals who are similar to existing employees will lead to greater homogeneity of skills, attitudes, and values. This homogeneity is thought to make organizations less flexible, less able to adapt to change, less innovative, and less capable of handling complex problems (Powell, 1998; Schneider, Goldstein, & Smith, 1995). Second, compliance with employment laws regarding the hiring of underrepresented groups in the workforce may be compromised by emphasizing supplementary fit over complementary fit. #16084 5 Third, as Chapman and Jones (2002) pointed out, organizations often experience circumstances that shrink the potential applicant pool (e.g., unattractive location or resources, tight labor markets). Under these conditions, organizations may be forced to adopt a complementary recruitment approach in order to find applicants with suitable skill sets but who may not have supplementary fit on other criteria. Last, organizations seeking out individuals for management or leadership positions may also be interested in the potential benefits of complementary fit. Leaders, by definition, are not only part of an organization, but also stand out from other employees on some dimensions. It is possible that individuals with leadership aspirations will be attracted to an organization that values them for their unique characteristics rather than their similarity to employees whom they might lead. Accordingly, recruiting messages encouraging complementary fit, whereby individuals recognize that they may have different skill sets, backgrounds, experiences, and values, but still feel like they belong (i.e., experience subjective P-O fit), may help organizations realize any benefits of heterogeneity in the workforce and avoid potential problems associated with an overly homogenous workforce. Because the complementary model of fit has yet to be examined in the context of applicant attraction, we believe that it is important to understand the extent to which individuals rely on different types of fit cues for evaluating their organizational attraction. Thus, in the current study we examined the extent to which individuals were attracted to organizations based on the type of fit promoted in the organizational culture (i.e., either supplementary or complementary). We also examined the role that individual differences play in applicant attraction to organizations espousing various types of fit. To our knowledge, no researchers have investigated why individuals might differ in their preferences for supplementary versus complementary organizational fit. Thus, in the present study we consider several individual #16084 6 difference variables that might influence the extent to which individuals are attracted to different recruitment advertisements. Applicant Attraction and Person-Organization Fit A preponderance of research suggests that individuals are attracted to organizations that are congruent with their personal characteristics (Chapman et al., in press). For instance, Cable and Judge (1996) found that individuals who perceived high levels fit with a particular organization were more likely to accept an employment offer from that organization. Studies examining applicant attraction and fit have also discovered that subjective or perceived fit mediates the relationship between objective P-O fit and attraction to the organization (e.g., Dineen, Ash, & Noe, 2002; Judge & Cable, 1997). With few exceptions, however, an assumption of the majority of studies examining P-O fit and attraction is that (a) individuals construe fit from a supplementary perspective (where fit is equated to similarity or matching of person and organization characteristics), and (b) individuals are attracted to organizations where they will have high supplementary fit. The complementary model of fit, which explains that individuals fit into an organization by possessing unique attributes that add to existing organizational attributes, is recognized as being a potentially important type of P-O fit (Kristof, 1996; Muchinsky & Monahan, 1987), yet this type of fit has been largely ignored in the literature. We found little research examining how different types of fit influence applicants’ attitudes about organizations. In one of the few studies that has examined complementary fit, Piasentin and Chapman (2004) found that both perceived supplementary fit and perceived complementary fit predicted incremental variance in overall subjective fit. Thus, there is some evidence to suggest that it may be beneficial to examine different types of fit and whether there are individual differences that lead to a greater emphasis #16084 7 on complementary rather than supplementary fit. As noted earlier, there are circumstances where it may be beneficial or necessary for organizations to adopt a complementary approach to attracting applicants. In addition, early evidence suggests that there may be some applicants who actually prefer a complementary fit with their organization (Piasentin & Chapman, 2004). However, we currently know nothing about whether applicants will adopt a complementary fit approach when seeking an employer, nor do we have understanding of whether there are individual differences in fit strategies used by applicants. Accordingly, we began by searching the individual differences literature to find constructs related to having a desire to be different and/or independent from others. This search revealed several potential individual differences that could moderate applicant attraction to complementary or supplementary messages embedded in job advertisements. Individual Differences in Applicant Attraction Several studies on P-O fit have investigated individual differences that moderate the effects of organizational characteristics on organizational attraction. For example, Judge and Cable (1997) examined how personality relates to applicants’ preferences for organizational cultures and proposed that individuals prefer work environments that are congruent with their personality. They found that individuals high in extraversion were more attracted to teamoriented environments whereas individuals high in openness to experience were more attracted to innovative work environments. Other evidence for individual differences comes from Bretz, Ash, and Dreher (1989) who found that that individuals high in need for achievement preferred organizations with individual based pay systems more than individuals low in need for achievement. #16084 8 Various theories on P-O fit can be used to explain why individual characteristics might moderate the influence of different recruitment messages on organization attractiveness (e.g., Byrne’s (1971) Similarity-Attraction model; Schneider’s (1987) Attraction-Selection-Attrition framework). The fundamental premise of these theories is that different types of people are attracted to different types of organizations; more specifically, people are attracted to organizations that value the same things as they do. Thus, organizations placing value on similarity should be more attractive to applicants who place importance on fitting in by being similar to others. Alternatively organizations placing value on diversity should be more attractive to applicants who place importance on fitting in by complementing others. An important focus of the present investigation is to learn if there are stable individual characteristics that can predict what type of organizational fit individuals look for in an organization. For instance, are some individuals more attracted to organizations that promote complementary fit, while others are more attracted to organizations that promote supplementary fit? If so, what type of individual difference variables might predict organizational attraction? Because this study represents a preliminary examination of potential individual differences affecting applicant P-O fit preferences, we examined several potential variables that might have significant moderating effects. Four categories of individual difference variables that might influence applicant attraction to different types of organizations were identified including (a) self-construal, (b) need motivations, (c) personality, and (d) demographics. Self-construal. One source of variance among individuals pertains to self-construal or self-image. Markus and Kitayama (1991) distinguished between independent and interdependent views of the self and explained how these self-construals influence various aspects of cognition, emotion, and motivation. The independent self-image is analogous to the individualistic #16084 9 orientation of Western culture, where self-interest is promoted above the collective, and people are seen as separate and distinct individuals. People who have an independent self-image focus on being unique, expressing themselves, and promoting their own goals (Singelis, 1994). These individuals adhere to notions such as independence, uniqueness, and self-reliance. Because individuals who have a strong independent self-image enjoy being different from others and standing out, they should be more likely than individuals low on independence to focus on complementary fit. Hypothesis 1a: Individuals with higher independent self-images will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize complementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than individuals lower in independent self-image. Another type of self-construal is referred to as the interdependent self. The interdependent view is analogous to non-Western collectivist values of connectedness, social context, and relationships (Singelis, 1994). Individuals who view themselves as interdependent tend to value belonging and fitting in, and are subservient to the wishes of the ingroup. Thus, people who have a strong interdependent self-image should be more likely than individuals low in interdependence to focus on the supplementary model of fit. Hypothesis 1b: Individuals with higher interdependent self-image will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize supplementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing complementary fit than individuals low in interdependent self-image. Need motivations. Another source of individual differences pertains to peoples’ need motivations; specifically, needs for achievement, dominance, affiliation, and autonomy, as well #16084 10 as need for uniqueness. The theory of work adjustment (Dawis & Lofquist, 1984) explains that a person will be satisfied with work only if his or her needs are fulfilled by the environment. Individuals high in need for achievement are typically characterized as goal seekers; they react positively to competition and consistently aspire to accomplish difficult tasks (Jackson, 1989). These individuals tend to desire personal responsibility and strive to maintain high standards. They are also thought to be more innovative than individuals low on this need (Turban & Keon, 1993). Because individuals with a high need for achievement attach great importance to distinguishing themselves from others (Atkinson & Raynor, 1974), it is assumed that these individuals will likely place more emphasis on complementary fit than supplementary fit. Hypothesis 2a: Individuals higher in need for achievement will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize complementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than individuals lower in need for achievement. Individuals with a high need for affiliation tend to focus their energy on being with friends and people in general, and on maintaining emotional ties with others (Jackson, 1989). Because individuals with a high need for affiliation seek acceptance and strive to appease others by doing whatever is perceived to be valued by others, these individuals may be more likely to value being similar to others as opposed to complementing others. Hypothesis 2b: Individuals higher in need for affiliation will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize supplementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than individuals lower in need for affiliation. #16084 11 Individuals high in need for dominance tend to seek leadership opportunities. They typically desire control and authority over other people and attempt to influence others by making suggestions, by giving their opinions and evaluations, and by controlling the activities of others (Steers, 1991). We expect that individuals with high dominance needs are more likely to seek out environments where they stand out amongst others, and will therefore prefer organizations that promote complementary fit. Hypothesis 2c: Individuals higher in need for dominance will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize complementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than individuals lower in need for dominance. Individuals high in need for autonomy generally value independence of thought; they prefer self-directed work, care less about others’ opinions and rules, and prefer to make decisions alone (Steers, 1991). These individuals tend not to respond to external pressures for conformity to group norms and tend to perform better when they are allowed freedom to control their own work pace. Because individuals with high autonomy needs are less likely to be concerned with conforming to others in the organization, we expect that these individuals will also prefer environments that emphasize complementary fit. Hypothesis 2d: Individuals higher in need for autonomy will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize complementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than individuals lower in need for autonomy. Individuals who value being unique and independent are considered to be high in need for uniqueness. According to Snyder and Fromkin (1977), these individuals strive to express #16084 12 themselves as unique and special individuals by differentiating themselves from other individuals and focusing on what sets them apart from others. From a fit perceptive, individuals with a high need for uniqueness may experience fit only when their needs for “standing out” are met. Thus, for these individuals, P-O fit may not reflect feelings of being similar to others (i.e., supplementary fit); rather, it is possible that fit is experienced for these individuals by feeling that they add unique value to the organization (i.e., complementary fit). Therefore, individuals high in need for uniqueness should be more likely than individuals low in need for uniqueness to focus on complementary fit. Hypothesis 2e: Individuals higher in need for uniqueness will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize complementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than individuals lower in need for uniqueness. Personality. One of the most popular sources of individual difference includes the various personality factors identified through factor analysis. This vast body of research suggests that a five-factor model of personality including extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience may be an optimal way of categorizing personality (Costa & McCrae, 1992). More recently, researchers have been pointing to a six factor model that includes honesty/humility in addition to the ‘Big Five’ noted earlier (e.g., Ashton et al., 2004; Lee & Ashton, 2004). Of these personality variables, we judged that openness to experience would be the most likely to moderate applicant impressions of recruiting ads advocating complementary or supplementary fit. Individuals who are high in openness to experience tend to be imaginative, original, autonomous, and broad-minded; they often seek out new and unconventional experiences and, in doing so, tend to stand out from others (Barrick & #16084 13 Mount, 1991). Conversely, people who are low in openness to experience tend to be more conventional and prefer familiarity to novelty. These individuals also tend to exhibit less creativity and divergent thinking than people high in openness to experience (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Thus, it is expected that individuals who are high in openness to experience may be more likely than individuals who are low on this trait to be attracted to organizations that depict a complementary fit with their organization. Hypothesis 3: Individuals high in openness to experience will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize complementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than individuals lower in openness to experience. Demographic variables. As noted earlier, one of the goals of a complementarity-based recruiting strategy is to promote diversity and ensure compliance with legislation covering protected groups. While we believe that true diversity of values, knowledge, skills, and abilities should be the goal of organizations, most legislation and research focuses on demographic characteristics as a proxy variable for diversity of values, or explicitly focuses on racial/gender diversity as a goal. Accordingly, this study examines the role of three demographic variables (age, gender, and race) on the attraction to supplementary and complementary focused recruitment advertisements. A handful of studies in the recruiting literature have examined the role that applicant demographics play in the attraction to jobs. Most have examined the influence of Affirmative Action statements on targeted groups’ attraction to the organization. The results of these studies suggest that the generic statements encouraging applications from women and minorities are typically viewed favorably by those groups, but that those statements have no effect on attraction for males and Caucasians (Avery, 2003). Given that complementary #16084 14 fit is worded to be inclusive of individuals with various backgrounds, we expect that females and visible minorities should be more attracted to those environments. Accordingly we predict: Hypothesis 4a: Females will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing complementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than males. Hypothesis 4b: Racial minorities will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize complementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing supplementary fit than Caucasians. Hollander’s (1958) theory of idiosyncrasy credits is useful for explaining why individuals with more work experience and tenure may be more able to engage in behaviors that deviate from the norm, without being sanctioned. In other words, longer-term members of organizations can accrue a certain amount of idiosyncrasy credits, which allows them freedom to deviate from normatively prescribed behavior (Katz & Kahn, 1978). Because older individuals tend to have more experience and are generally perceived as being more valuable in the workplace, they may be more likely to seek out ways that they can express their individuality. On the other hand, younger people generally have less work experience and are more likely to rely on cues in the environment for how to behave in the workplace (Miceli & Near, 1992). Accordingly, we expect that age will have a moderating effect on the relationship between the type of recruitment advertisement and applicant attraction. Hypothesis 4c: Younger applicants will be more attracted to recruitment advertisements that emphasize supplementary fit and less attracted to recruitment advertisements emphasizing complementary fit than older applicants. #16084 15 Method Participants Participants were 128 undergraduate students from a medium-sized Canadian University who received course credit for their participation. The average age of participants was 23 years (SD = 4.87), 86% were female, 62% were Caucasian, and 67% were currently employed either part-time or full-time. Experimental Design A mixed experimental design was used, incorporating both within-persons and betweenpersons components. Each participant was presented with six recruitment advertisements, three of which emphasized supplementary fit, and three of which depicted emphasized complementary fit. Participants received one of 32 versions of the survey, which counterbalanced the order of presentation of the recruitment advertisements. Recruitment Advertisement Descriptions Recruiting advertisements were created to look like typical job advertisements that might be found in a newspaper or on a web site (see Appendix A). The ads were designed to be generic and only provided information about the organization to avoid unwanted variance due to systematic differences in preferences for specific types of jobs. Each advertisement contained a manipulation which either emphasized a supplementary fit or a complementary fit. Prior to reading the recruitment advertisements, each participant was instructed to adopt the role of a job seeker in that: (1) they are actively seeking a job; (2) the job market is excellent, providing many job opportunities; (3) each organization would provide them with job opportunities in their area of interest; (4) each organization would provide excellent promotion opportunities; (5) the pay and benefits offered by each organization are competitive and #16084 16 equivalent; and (6) each organization is in their preferred geographic location. Feedback from participants suggested that adopting a job seeking role was familiar to them and easy to do. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each recruitment advertisement was realistic and overall, a majority of participants rated the ads as at least somewhat realistic. Shultz, Jones, and Chapman (2004) reported that undergraduate students, whether they are currently employed or unemployed, frequently look at newspaper ads or scan internet job ads to determine the availability of jobs, suggesting that most participants were familiar with a job seeking role. Meta-analytic results also indicate that experimental manipulations are successful in modeling job applicant behaviors and cognitions, particularly in the early stages of recruitment being simulated in this study (Chapman et al., in press). Individual Difference Measures Prior to reading the recruitment advertisements, participants completed five individual difference scales. All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Self-image. Items adapted from Singelis’ (1994) Self-Construal Scale were used to assess the independent and interdependent views of self. Ten items were used to assess the independent self-image ( = .72), including “I enjoy being unique and different from others in many respects” and “I am comfortable being singled out for praise or rewards.” An additional 10 items were used to assess the interdependent self-image ( = .71), including “It is important for me to maintain harmony within my group” and “I respect people who are modest about themselves”. Need motivations. The Manifest Needs Questionnaire (Steers & Braunstein, 1976) contains 20 items designed to measure four different need motivations: achievement (e.g., “I try #16084 17 to perform my best at work”), affiliation (e.g., “When I have a choice, I try to work in a group instead of by myself”), dominance (e.g., “I seek an active role in the leadership of a group”), and autonomy (e.g., “I would like a job where I can plan my work schedule myself”). Internal consistencies for these subscales in this sample were found to be .73, .70, .84, and .66, respectively. Snyder and Fromkin’s (1977) Need for Uniqueness Scale was used to measure participants’ need for uniqueness ( = .85). This scale contains 32 items designed to measure the extent to which individuals are nonconformists and prefer to stand out as opposed to blend in amongst others. Sample items include “I prefer being different from other people” and “Being a success in one’s career means making a contribution that no one else has made”. Personality. Openness to experience was measured using a subscale from the NEO FiveFactor Inventory – Form S (Costa & McCrae, 1992). This subscale comprises 12 items including “I have a lot of intellectual curiosity” and “I often enjoy playing with theories or abstract ideas” ( = .76). Demographic variables. Single items were designed to collect information on participant age, gender and race. Race was later re-coded into Caucasian and Minority. Dependent variable. Organization attraction was measured with two items: “How attractive would you find this organization as a place to work?” (1 = very unattractive; 7 = very attractive) and “How likely is it that you would apply for a job in this organization?” (1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely). These items were rated for each recruitment ad independently (internal consistencies across the six ads ranged from .88 to .93). #16084 18 Results Correlations between the individual difference measures and organizational attraction are presented in Table 1. As expected, the main effect of ad type was not statistically significant, t (127) = 1.89, p = .06, although complementary-focused recruitment ads were rated as being slightly more attractive (M = 4.94, SD = .88) than supplementary-focused recruitment ads (M = 4.74, SD = .92). P-O Fit Analyses To investigate whether the individual difference variables moderated the effects of the type of recruitment advertisement on organizational attraction we conducted moderated regression analyses. For these analyses, organizational attributes (i.e., supplementary vs. complementary fit) were dummy coded. We then computed the interaction terms between the organizational attributes and each of the individual difference variables. When the interaction explained a significant portion of variability in the dependent variable, we plotted the interaction effects following procedures discussed by Cohen and Cohen (1983). Specifically, we plotted the slopes for high and low values (±1 SD from the mean) of the individual characteristic for each type of recruitment advertisement. As shown in Figure 1, individuals with a strong independent self-image were more attracted to organizations emphasizing complementary fit than organizations emphasizing supplementary fit (β = .133, p = .03). Surprisingly, however, individuals with a strong interdependent image were also more attracted to organizations promoting complementary fit than organizations promoting supplementary fit (β = .149, p = .02). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was only partially supported. Hypothesis 2 predicted that individual differences in need motivations would moderate the relationship between organizational attributes and applicant attraction. As shown in Figure 2, #16084 19 individuals high in need for achievement were more attracted to organizations that fostered a complementary fit than organizations fostering a supplementary fit (β = .14, p = .03). This same pattern was found for individuals high in need for dominance (β = .14, p = .03), and need for autonomy ((β = .149, p = .02), thus providing support for Hypothesis 2. Contrary to prediction, individuals high in need for affiliation were not significantly more likely to be attracted to organizations fostering a supplementary fit as opposed to a complementary fit (β = .122, p > .05). In further support of Hypothesis 2, individuals high in need for uniqueness (β = .147, p = .02) were more attracted to organizations promoting a complementary fit than individuals low in need for uniqueness. Hypothesis 3 predicted that individuals high in openness to experience would be more attracted to organizations promoting a complementary fit than individuals low in openness to experience. As Figure 3 illustrates, this hypothesis was also supported (β = .175, p < .01). The results for the demographic variables were mixed. The slopes of the relationships between gender and attraction to the complementary-focused recruitment ads (r = -.02, p = .86) and the supplementary-focused recruitment ads (r = -.01, p = .90) show that gender did not play a role in our sample and, therefore, Hypothesis 4a was not supported. Perhaps more intriguing was the result for ethnic minorities in that the opposite results were found to what was expected. Table 1 reveals that race had no effect on the attractiveness of complementary-focused recruitment ads (r = .03, p = .74) but that ethnic minorities were more attracted to the supplementary-focused advertisements than Caucasians (r = .27, p = .003). Thus, Hypothesis 4b was not supported. Hypothesis 4c predicted that younger participants would be more attracted to recruitment ads that emphasized supplementary fit and less attracted to ads that emphasized complementary fit. Although the slopes for these relationships were in the predicted direction (r #16084 20 = .08, p = .41 and r = -.16, p = .08 for supplementary and complementary ads, respectively), they failed to reach statistical significance. Thus, Hypothesis 4c was not supported. Discussion A primary goal of this study was to examine whether individuals are differentially attracted to environments fostering a supplementary or complementary fit. The results suggest that individual differences did play a role in attraction to organizations employing ads emphasizing complementary or supplementary P-O fit. Although the effect sizes were not large, significant interactions were found for most of the potential moderators tested. Self-construal of independence versus interdependence differentially predicted attraction to complementary and supplementary based recruitment ads. This finding has implications for understanding how P-O fit might be evaluated in cultures that emphasize interdependence (e.g., Japan, China), where supplementary fit should prove to be more important than in countries emphasizing independence (e.g., the United States). Moderators involving individual differences in need motivations also proved to be successful in differentiating between applicants focused on complementary fit and those more focused on supplementary fit. Individuals higher in need for achievement, dominance, uniqueness, and autonomy were all more attracted to complementary-focused recruitment ads. This finding may be important for practitioners who are recruiting for positions where these characteristics are desirable (e.g., leadership, management, innovation, and working with little supervision). Personality also played a role in perceptions of the attractiveness of the complementaryand supplementary-focused recruitment advertisements. In fact, personality proved to be the strongest moderator of this relationship. Individuals higher in Openness to Experience were #16084 21 more attracted to complementary recruitment ads than supplementary recruitment ads. For practitioners seeking applicants where openness to experience is desirable, we would recommend that job ads emphasizing complementary fit would be more effective. For researchers, we suggest that openness to experience may be the best single moderator for identifying individuals who may place a greater emphasis on complementary rather than supplementary fit. Demographic variables did not play a strong role in perceptions of recruitment advertisements that vary only on their complementary/supplementary focus. Neither gender nor age was significantly related to applicant attraction, whereas ethnicity played a somewhat contradictory role than what we expected. A finer grained analysis of our data may have revealed why this counterintuitive result was found. Most of the ethnic minorities in our sample were of Chinese (20%) or other Asian origins (11%). These cultures are among the highest with respect to an interdependent self-construal. Table 1 reveals that there was a significant relationship between ethnicity and an interdependent self-construal. Accordingly, it is likely that ethnic minorities were more attracted to supplementary-focused recruitment ads because they emphasized values of interdependence and similarity rather than independence and uniqueness. This result may be different for other ethnic minorities. Strengths and Limitations We believe that the strength of this study derives from the fact that it represents the first study that has examined the extent to which applicant attraction relates to different types of P-O fit. An important contribution of this study to the P-O fit literature is the investigation of potential individual differences that influence applicant attraction to organizations that foster different organizational cultures. #16084 22 The design of this study has limitations. We created recruitment advertisements based on fictitious companies, and the information provided to participants about each company was limited to descriptions of the type of culture promoted in the organization (i.e., one based on supplementarity or complementarity). Another limitation is that study participants were not actual job applicants but undergraduate students. Although 70% of the participants indicated that they were presently employed either on at least a part-time basis and 20% of participants indicated that they were presently searching for employment, these individuals may not be representative of actual applicants, nor are the recruitment advertisements likely to accurately reflect typical advertisements they would come across in their job search. Implications and Directions for Future Research Due to economic and demographic changes in today’s workforce, organizations will be forced to consider recruitment strategies that will attract and retain a diverse workforce. With an increasingly diverse workforce (Powell, 1998) and rising awareness among corporations to promote organizational diversity (Richard, 2000), it may not be feasible or even desirable to target recruitment and selection efforts around a supplementary model of fit. In fact, finding individuals who value complementarity may give an organization a competitive advantage by allowing for greater creativity, innovation, and flexibility in the organization (Schneider, 1987). In terms of understanding individual difference variables that can predict the types of fit that individuals value, organizational recruiters may be able to judge the likelihood that an applicant will fit their culture by considering the applicants' personality, needs, and self-construal, which would also aid in their efforts to target recruitment strategies based on the type of fit they are looking for. #16084 23 References Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., Perugini, M., Szarota, P., De Vries, R. E., Di Blas, L., Boies, K., & De Raad, B. (2004). A six-factor structure of personality-descriptive adjectives: Solutions from psycholexical studies in seven languages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 356-366. Atkinson, J. W., & Raynor, J. O. (1974). Motivation and achievement. New York: Winston & Sons. Avery, D. R. (2003). Reactions to diversity in recruitment advertising – Are differences black and white? Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 672-679. Barber, A.E. (1998). Recruiting employees: Individual and organization perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1-26. Breaugh, J.A., & Starke, M. (2000). Research on employee recruitment: So many studies, so many remaining questions. Journal of Management, 26, 405-434. Bretz, R. D., Ash, R. A., & Dreher, G. F. (1989). Do people make the place? An examination of the attraction-selection-attrition hypothesis. Personnel Psychology, 42, 561-582. Bretz, R. D., & Judge, T. A. (1994). Person-organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44, 32 -54. Bretz, R. D., Rynes, S. L., & Gerhart, B. (1993). Recruiter perceptions of applicant fit: Implications for individual career preparation and job search behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 43, 310-327. #16084 24 Byrne, D. (1971). The attraction paradigm. New York: Academic Press. Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875-884. Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person-organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67(3), 294-311. Chapman, D. S., & Jones, D.A. (2002, August). Recruiting as persuasion: Making the square hole appear round and making the round peg feel square. In D. J. Cohen (Chair), Recruitment and Retention. Symposium conducted at the 62nd annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Denver, CO. Chapman, D. S., Uggerslev, K. L., Carroll, S. A., Piasentin, K. A., & Jones, D. A. (in press). A meta-analytic review of factors influencing applicant attraction to organizations and job choice. Journal of Applied Psychology. Cohen, J, & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory and NEO Five-Factor Inventory professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Dawis, R. V., & Lofquist, L. H. (1984). A psychological theory of work adjustment. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Dineen, B. R., Ash, S. R., & Noe, R. A. (2002). A web of applicant attraction: Personorganization fit in the context of web-based recruitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 723-734. Haptonstahl, D. E., & Buckley, T. (2002). Applicant fit: A three-dimensional investigation of #16084 25 recruiter perceptions. Paper presented at the 17th annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Toronto, Canada. Hollander, E. P. (1958). Conformity, status, and idiosyncrasy credit. Psychological Review, 65, 117-127. Jackson, D. N. (1989). Personality Research Form Manual, 3rd ed. Port Huron, MI: Research Psychologists Press, Inc. Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (1997). Applicant personality, organizational culture, and organizational attraction. Personnel Psychology, 50, 359-394. Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1-28. Lauver, K. J., & Kristof-Brown, A. (2001). Distinguishing between employees’ perceptions of person-job and person-organization fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 454-470. Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO Personality Inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research. Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224-253. Miceli, M. P., & Near, J. P. (1988). Individual and situational correlates of whistle-blowing. Personnel Psychology, 41, 267-281. Michaels, E., Handfield-Jones, H., & Axelrod, B (2001). The war for talent. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Muchinsky, P. M., & Monahan, C. J. (1987). What is person-environment congruence? #16084 26 Supplementary versus complementary models of fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31, 268-277. Piasentin, K. A., & Chapman, D. S. Piasentin, K. A., & Chapman, D. S. (2004, April). Perceived Similarity and Complementarity as Predictors of Subjective PersonOrganization Fit. Poster presented at the 19th annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago, Illinois. Powell, G. N. (1998). Reinforcing and extending today’s organizations: The simultaneous pursuit of person-organization fit and diversity. Organizational Dynamics, 26, 50-62. Richard, O. C. (2000). Racial diversity, business strategy, and firm performance: A resourcebased view. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 184-177. Rynes, S. L. (1991). Recruitment, job choice, and post-hire consequences: A call for new research directions. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 399-444). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2002). Is job search related to employment quality? It all depends on the fit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 646-654. Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437-453. Schneider, B., Goldstein, H. W., & Smith, D. B. (1995). The ASA framework: An update. Personnel Psychology, 48 (4), 747-762. Shultz, J., Jones, D.A. & Chapman, D.S. (2004, April). The Elaboration Likelihood Model Job Ads and Job Choices. Poster presented at the 19th annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago, Illinois. Snyder, C. R., & Fromkin, H. L. (1977). Abnormality as a positive characteristic: The #16084 27 development and validation of a scale measuring need for uniqueness, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86, 518-527. Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self constructs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 580-591. Steers, R. M. (1991). Introduction to organizational behavior (4th ed.). New York: Harpers Collins. Steers, R. M., & Braunstein, D. N. (1976). A behaviorally-based measure of manifest needs in work settings. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 9, 251-266. Turban, D. B., & Keon, T. L. (1993). Organizational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 184-193. Turban, D. B, Lau, C., Ngo, H., Chow, I. H. & Si, S.X. (2001). Organizational attractiveness of firms in the People’s Republic of China: A person-organization fit perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 194-206. #16084 6 5.8 5.6 Organization Attraction 5.4 High Independence Low Independence 5.2 5 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 4 Supplementary Complementary Type of Recruitment Ad Figure 1a. The relationship between type of recruitment advertisement and organization attraction for individuals high in independence and individuals low in independence. 6 5.8 5.6 Organization Attraction 5.4 5.2 High Interdependence Low Interdependence 5 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 4 Supplementary Complementary Type of Recruitment Ad Figure 1b. The relationship between type of recruitment advertisement and organization attraction for individuals high in interdependence and individuals low in interdependence. 28 #16084 29 6 5.8 5.6 Organization Attraction 5.4 5.2 High Achievement Low Achievement 5 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 4 Supplementary Complementary Tyoe of Recruitment Ad Figure 2a. The relationship between type of recruitment advertisement and organization attraction for individuals high in need for achievement and individuals low in need for achievement. 6 5.8 5.6 Organization Attraction 5.4 5.2 High Dominance Low Domincance 5 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 4 Supplementary Complementary Type of Recruitment Ad Figure 2c. The relationship between type of recruitment advertisement and organization attraction for individuals high in need for dominance and individuals low in need for dominance. #16084 30 6 5.8 5.6 Organization Attraction 5.4 5.2 High Autonomy Low Autonomy 5 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 4 Supplementary Complementary Type of Recruitment Ad Figure 2d. The relationship between type of recruitment advertisement and organization attraction for individuals high in need for autonomy and individuals low in need for autonomy. 6 5.8 5.6 Organization Attraction 5.4 High Uniqueness Low Uniqueness 5.2 5 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 4 Supplementary Complementary Type of Recruitment Ad Figure 2e. The relationship between type of recruitment advertisement and organization attraction for individuals high in need for uniqueness and individuals low in need for uniqueness. #16084 6 5.8 5.6 Organization Attraction 5.4 5.2 High Openness Low Openness 5 4.8 4.6 4.4 4.2 4 Supplementary Complementary Tyoe of Recruitment Ad Figure 3. The relationship between type of recruitment advertisement and organization attraction for individuals high in openness to experience and individuals low in openness to experience. 31 #16084 32 Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Study Variables Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1. Age 22.79 4.87 -- 2. Gender 1.86 .35 .03 -- 3. Ethnicity 1.38 .49 -.08 -.01 -- 4. Need for Uniqueness 4.15 .62 .09 -.17 -.06 (.85) 5. Need for Achievement 6.01 .68 .14 .10 -.14 -.04 (.73) 6. Need for Affiliation 4.08 .93 -.16 -.02 -.06 .04 .00 (.70) 7. Need for Dominance 4.64 1.12 .09 -.08 .05 .52 .17 .13 (.84) 8. Need for Autonomy 5.52 .78 .15 -.16 .03 .47 .14 -.19 .39 (.66) 9. Interdependent Self-Image 4.55 .67 -.19 -.11 .23 -.41 .17 .07 -.24 -.30 (.71) 10. Independent Self-Image 4.83 .75 .03 -.07 -.02 .57 .17 .13 .45 .37 -.20 (.72) 11. Openness to Experience 4.98 .79 .13 -.05 .10 .45 .02 .05 .28 .24 -.25 .29 (.76) 12. Supplementary Attraction 4.74 .92 .08 -.01 .27 .03 .12 .07 .09 .03 .19 .03 .00 (.??) 13. Complementary Attraction 4.94 .88 -.16 -.02 .03 .17 .11 .05 .10 .18 .09 .11 .28 .12 13 (.??) Note. Values greater than .17 are significant at p < .05, values greater than .23 are significant at p < .01, values greater than .30 are significant at p < .001. Because of missing data, Ns range from 124 to 128. Gender was coded as 1=male, 2=female. Ethnicity was coded as 1=Caucasian, 2=other. Internal consistencies appear on the diagonal in parentheses. #16084 33 Appendix A – Recruitment Advertisements Careers at Casiko, Inc. Careers at Vexica Join our growing team and enjoy a continuous learning experience in a fast-paced, friendly environment! Join our growing team and enjoy a continuous learning experience in a fast-paced, friendly environment! In our organization, every employee is equal and contributes equally to the identity of the organization. In our organization, every employee is unique and contributes uniquely to the company’s goals. Unity of thought is the key to our success Diversity of thought is the key to our success We are always looking for highly motivated individuals who enjoy working with others who share similar abilities and perspectives. We are always looking for highly motivated individuals who strive to express their unique abilities and perspectives. For more information about our career opportunities visit www.casiko/careers.ca For more information about our career opportunities visit www.vexica/careers.ca Are you looking for an exciting Career Opportunity? Are you looking for an exciting Career Opportunity? Be part of one of the fastest growing industries in Canada Be part of one of the fastest growing industries in North America At Sentena, we pride ourselves in providing a working environment where like-minded people strive for the best solutions. At DXI, we pride ourselves in being open and direct, pushing employees to think “outside the box”, and to consider new perspectives. We are looking for individuals who enjoy working with similar others and who aspire to the same common values. We are looking for individuals who seek to express their values, their ideas, and their creativity. Contact us today at www.sentena/careers.com Contact us today at www.dxi/careers.com Join our team! Join our team! Looking for an organization where you can blend in amongst your co-workers and work collectively with other talented people like you? Looking for an organization where you can stand out amongst your co-workers and really express your creativity? Our workplace operates as a family where individuals share similar work styles, abilities, and skills, and our employees are committed to the same universal values. Our workplace fosters a variety of work styles, abilities, and skills and our employees are committed to a variety of diverse values. We are seeking talented individuals who aspire to the same common work ethic – people who work together to ensure the success of the organization. We are seeking talented individuals who aspire to be different – people who are not afraid to express themselves as individuals. Visit www.hartland.com to learn more about us Visit www.mckenziegroup.com to learn more about us Hartland Corp. McKenzie Group