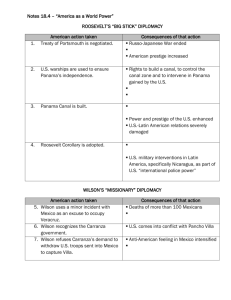

MAP

advertisement