The Mastercard IPO - Harvard Negotiation Law Review

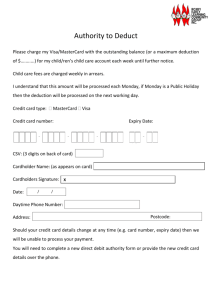

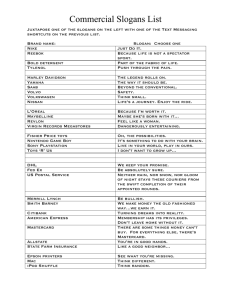

advertisement

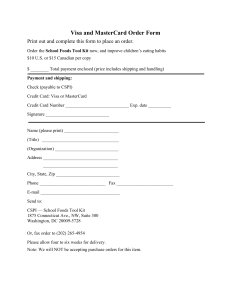

WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... 12 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 137 Harvard Negotiation Law Review Winter 2007 Article The MasterCard IPO THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS BRAND Victor Fleischer<<pi>> Copyright (c) 2007 Harvard Negotiation Law Review; Victor Fleischer Introduction This case study examines the legal infrastructure of the MasterCard IPO. I argue that the IPO design undertook two tasks related to the MasterCard brand: (1) managing regulatory costs (in particular, reducing antitrust exposure) and (2) enhancing the company’s image as a safe, secure brand that facilitates a middle-class consumer lifestyle. These tasks are unusual for an IPO, a transaction which is normally thought of as an exercise in managing transaction costs. 1 Here, the legal structure of the deal not only affected brand image in the usual sense (how consumers view the Priceless brand). It also affected brand image in the sense that it influences how regulators, judges, and juries, standing in the shoes of consumers, view the firm. There is a potential positive feedback effect: increased transparency and independence from the member banks reduces antitrust exposure, which in turn protects the image of the firm as consumer-friendly, which in turn reduces the likelihood of hostile action by antitrust regulators. In this Article, I focus on two unusual structural elements: a “reverse” dual-class voting structure and the creation of a charitable foundation. *138 “Reverse” Dual-Class Voting. The dual-class voting structure is unusual because the insiders (the member banks) retain more economic exposure than voting rights, flipping the usual dual-class voting structure upside-down.2 This element of the structure is a magnificent example of what I call “regulatory cost engineering”: driving a wedge between the economics of a deal and its treatment for legal or regulatory purposes. The member banks retain effective veto power and some influence over the company, and they retain much of the economic interest in the firm. However they give away formal voting power and control, thereby reducing their antitrust liability going forward. Charitable Foundation. The MasterCard Foundation is an example of both regulatory cost engineering and branding. The Foundation holds a large block of MasterCard stock. It may not sell the stock (at least for several years), yet it will receive dividends and additional cash contributions that it will use for charitable purposes. If the member banks were truly feeling altruistic, of course, they could have found more efficient ways to give money away. 3 Indeed, elements of the Foundation’s structure - its function as a corporate governance device, and the limits on its ability to sell MasterCard stock or engage in significant charitable giving for several years - suggest that genuine altruism is at best an ancillary goal. The Foundation’s role as a corporate governance device is particularly innovative. It establishes a block shareholder interested in preserving long-term value. It allows the member banks to maintain some influence over the direction of the company without triggering antitrust concerns. And it’s a bulletproof takeover shield.4 I expect stock-holding charitable foundations to become more commonplace in the United States as hedge funds step up shareholder pressure. 5 *139 If successful, then the Foundation’s activities could have positive effects both in terms of revenue and in the regulatory arena. Whether the charitable foundation will, in fact, be an effective branding device is another question. One does not have to be overly cynical to see a disconnect between the MasterCard Foundation’s purported philanthropic goals and its low levels of anticipated charitable giving. Early press coverage has not been good. 6 In sum, the utility of the charitable foundation as a regulatory arbitrage tool is clear; its ability to improve the welfare of anyone other than the member banks is unproven. The Lawyer’s Role. The deal’s structure is fascinating on its own terms, but this case study also provides an occasion to © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... consider exactly why lawyers play such an extensive role in structuring deals. Is the lawyer’s role merely to be a “monkey f***-ing scribe,” as it was put on one voicemail that circulated widely on the Internet? 7 Despite what one hears from beleaguered young associates, this case study shows that the transactional lawyer’s role is not limited to existential-angst-producing document generation. In navigating clients through the regulatory thicket, lawyers have an obvious comparative advantage over bankers and managers. With respect to managing brand equity, the lawyer’s strategic role is more context-specific. Here, the charitable foundation and the dual-class structure are the legal tools used to help manage the brand image of the company. I conclude, however, that the lawyers may not have gone quite far enough in protecting the brand; lawyers more sensitive to branding concerns might have polished the quartz a little longer before presenting it as a diamond. I. Deal Background8 IPOs are structured primarily to manage the information asymmetry *140 between investors and shareholders.9 A public stock offering’s success or failure is normally measured in terms of the cost of capital. Did the company raise as much money as possible per share sold? Did it efficiently convey information to potential investors, or did it leave money on the table? Are company insiders or investment bankers extracting rents in the process? Elsewhere, I have argued that in addition to these concerns about managing transaction costs, the structures of IPOs and other deals have branding implications.10 Deal structure can send a valuable message to consumers about the company’s goals. In this case, the deal structure is best understood as accomplishing two unusual goals: managing brand equity and managing regulatory costs. The deal is not really about raising money at all. In a world without antitrust regulation, or in a world where consumers were indifferent as to the brand of credit card they used, this deal would look very different. Indeed, it would not have occurred at all. The MasterCard Brand MasterCard is a network that provides payment-processing services to merchants on behalf of its member banks. The “Master Charge” network was created by some California banks in the 1960s to compete with the BankAmericard (now Visa). Renamed “MasterCard” in 1980, MasterCard is the second-leading payment system in the U.S., trailing only Visa. In the late 1990s, MasterCard revamped its image with its “Priceless” advertising campaign. The campaign sends the message that nothing (including the unavailability of cash) should stop you from creating priceless memories with friends and family. Each ad begins with images of items or services purchased (presumably with a credit card) and a price, followed at the end by a phrase identifying some intangible - such as quality time with one’s children - that can’t be purchased. Then the word “Priceless” flashes on the screen, accompanied by the voiceover, “There are some things that money can’t *141 buy. For everything else, there’s MasterCard.” The ad campaign positions MasterCard as a financial services company that supports family values and understands the limits of consumerism. The ads de-commodify the payment service by associating the MasterCard name with warmer feelings of friends and family, not late fees and interest charges. The campaign, which has run in more than 100 countries and inspired hundreds of parodies on Late Night with David Letterman, the Simpsons, and the Internet, is credited with reversing MasterCard’s fifteen-year decline in market share. Consumers also associate the MasterCard brand with safety and security. In a 1996 consumer survey, MasterCard and Visa were recognized as cards that can be used wherever needed; MasterCard alone was seen as “dependable in emergencies.”11 MasterCard aggressively protects its brand. It has sued potential infringers, including Ralph Nader, 12 who have used the “Priceless” tagline. Merchants and member banks must follow strict guidelines in how they present the “acceptance marks” (which signal to consumers where MasterCard is accepted) and “brand marks” (used by member banks and others to promote MasterCard-branded services).13 The brand, however, has also been somewhat tarnished by antitrust litigation. While the impact of antitrust litigation on average consumers has been minimal, antitrust regulators, standing in the shoes of consumers, increasingly seem to view MasterCard and Visa, *142 acting together as the two dominant U.S. credit card companies, as the next Microsoft.14 Antitrust MasterCard’s antitrust problems originate from the unusual demands of building a payment-processing network that relies on several parties interacting at once. Card-issuing banks attach the MasterCard logo to cards, but each bank sets up its own interest rates and annual fees charged to consumers. MasterCard sets an interchange fee that its member banks charge to the merchants’ banks. MasterCard does not issue cards, charge annual fees to consumers, determine interest rates, or force © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 2 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... merchants to set a particular discount rate on transactions. As a result, there are four parties - the consumer, the merchant, the consumer’s bank, and the merchant’s bank - that all must be coordinated. Suppose you go to Circuit City and buy an iPod Shuffle for $100 with your MasterCard-branded credit card issued by MBNA. Circuit City sends the transaction data to its bank, also known as the “Acquiring Bank,” and receives back the purchase price less the “merchant discount.” Thus, if the merchant discount were 2% (a typical amount), Circuit City would receive $98 from the Acquiring Bank. The Acquiring Bank then sends the data to your own bank, known as the “Issuing Bank.” The Acquiring Bank receives the purchase price ($100) less the interchange fee, which is set by MasterCard. Thus, if the interchange fee were 1.4%, the Acquiring Bank would receive $98.60 from the Issuing Bank, pocketing $0.60 in gross revenue. Closing the circle, the Issuing Bank would then present you with a charge for $100 on your credit card statement. At the end of the day, Circuit City has received $98 and the other parties involved (the Acquiring bank, the Issuing bank, and the payment network) split up the remaining $2. *143 Typical Point of Sale Transaction TABULAR OR GRAPHIC MATERIAL SET FORTH AT THIS POINT IS NOT DISPLAYABLE Competition thrives among issuing banks seeking consumers and acquiring banks seeking merchants. At the level of coordination among the various participants, however, only four networks have significant market share: MasterCard, Visa, Discover, and American Express. Because a network becomes more valuable as more participants join, there is a steep barrier to entry. Although MasterCard and Visa are competitors, they have had a system of “dual governance” which allows some member banks to have directors on the board of both organizations. And until a recent judicial holding banned the policy, both MasterCard and Visa had prohibited member banks from issuing other credit cards. This practice, known as brand exclusion, was implemented by MasterCard’s “Competitive Programs Policy” and a by-law in Visa’s governing charter. Other allegedly anticompetitive behavior included a requirement that merchants “honor all cards,” forcing any merchant who accepted a MasterCard-branded debit card to also accept MasterCard-branded credit cards, which charge higher fees. MasterCard and Visa also continue to prohibit merchants who accept their cards from imposing surcharges on credit card users.15 Consequently, the cost of high interchange fees is not passed along to credit card users alone. Instead, all consumers bear the cost, including customers who pay by cash, as merchants raise prices to reflect the cost of the merchant discount. *144 Interchange fees, in other words, act as a tax on cash-paying customers.16 This and other alleged anti-competitive behavior has led to a long history of antitrust litigation for MasterCard and Visa, including a recent $3 billion settlement. Globalization and Innovation In 2002, MasterCard acquired Europay International, the leading European credit card network; the European banks that owned Europay now hold a substantial stake in MasterCard. The European banks are accustomed to having a lot of say about MasterCard’s operations in Europe, and distrust reportedly affected the IPO negotiations. 17 As discussed more below, the European banks want to retain significant control over MasterCard’s policies in Europe. Looking ahead, trends in the credit card industry make the integrity of the brand a crucial strategic asset. Innovation in the payment industry, such as shopping on-line and touchless transactions (as when you wave your payment card at the gasoline pump), require MasterCard to keep up with new competitors. Globalization also poses both an opportunity and a challenge. MasterCard wants to welcome the billions of people entering the middle-class consumer lifestyle worldwide. Expanding the brand, however, makes maintaining brand integrity that much more important. The Deal Structure Historically, MasterCard was a membership corporation, wholly owned by its member banks. MasterCard incorporated as a Delaware stock corporation in 2002 in connection with the Europay acquisition and in anticipation of a possible IPO. Currently, MasterCard’s common stock is 100% owned by its member banks. The largest owners are JP Morgan Chase (10%), Citigroup (9%), Bank of America (6%), and HSBC (5%). 18 © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 3 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... In the IPO, MasterCard created three classes of common stock: Class A, Class B, and Class M. The current shares of the member *145 banks were reclassified, with each existing shareholder receiving 1.35 shares of Class B common stock and 1 share of Class M stock in exchange for each share of old common stock. Class A Shares (High-Vote) The public now holds most of the Class A shares. The shares were created by redeeming a certain number of the member banks’ Class B shares; in effect, the member banks are selling some of the economic interest to the public. $650 million in proceeds from the sale of Class A shares was held back from U.S. banks to reflect their greater share of antitrust liability; the remainder (about $2 billion) was used to redeem some of the interests of the member banks. Member banks are not permitted to hold Class A shares, which have full economic and voting rights. A newly-created charitable foundation, incorporated in Canada, holds about 17% of the newly-issued Class A shares. Class B Shares (No-Vote) The Class B shares are held only by the member banks. The shares have no voting rights. Each share of Class B stock is convertible into one share of Class A stock on the fourth anniversary of the IPO, subject to a right of first refusal by other Class B shareholders.19 Class M Shares (Veto Power on Major Transactions) Class M shares have neither economic rights nor any normal voting rights. Major transactions, however - including the sale of the company, a merger, a waiver of beneficial ownership limits, or the discontinuation of the payments business - require the approval of a majority of Class M shareholders. *146 Voting Rights vs. Economic Rights TABULAR OR GRAPHIC MATERIAL SET FORTH AT THIS POINT IS NOT DISPLAYABLE Board-Within-A-Board A new twelve-person staggered board was named. Going forward, nine members will be elected by Class A members (eight of whom will be independent from the company and member banks; the ninth will be the CEO); three members will be elected by Class M shareholders (the member banks). MasterCard also has a separate, special board, or “board-within-a-board,” elected by the European Class M holders. This feature ensures that the European banks (who came on recently with the Europay acquisition) can retain leadership over European issues. The European board supervises a broad range of activities in Europe, including membership rules, fines, assessments and fees, and affinity and co-branding rules. The main board can only override the decisions of the European board with a 75% super-majority vote. Anti-Takeover Devices MasterCard employs a number of anti-takeover devices, including: (1) no entity may own more than 15% of Class A or Class B shares, or command more than 15% of total voting power; (2) no member bank or affiliate may own Class A stock; *147 (3) the board must be staggered according to the structure discussed above; (4) up to three directors will be elected by the member banks; © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 4 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... (5) amending the certificate of incorporation or by-laws requires a vote of 80% or more of the outstanding shares; and (6) major transactions require approval by a majority of Class M shareholders. MasterCard Foundation The Foundation is organized under Canadian law. It holds 17% of the Class A shares, giving the Foundation 17% of the vote and 10% of the economics of the company. The Foundation may not sell this stock until twenty years and eleven months following the IPO, except to the extent necessary to satisfy charitable giving requirements under Canadian law (and even then only starting four years after the IPO). The five initial directors of the Foundation will be selected by a three-member “blue-ribbon” panel, subject to the veto of the Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee of the new MasterCard board (the blue-ribbon panel will itself be selected by two current directors and the current CEO). Going forward, the continuing directors will select successors in consultation with the Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee. Proceeds The IPO proceeds were used to redeem shares from the member banks. Six-hundred and fifty million dollars, however, were held back from U.S. banks, reflecting their greater responsibility for antitrust liability. II. Reverse Dual-Class Voting In the usual dual-class structure, like the recent Google IPO, insiders retain a special “superior” class of stock that carries with it ten times the voting rights of the other common shareholders; consequently, insiders are able to retain disproportionate control over the company. About six percent of U.S. public companies have more than one class of stock, most of which are organized in this high-vote/low-vote structure, which may be justified as retaining a focus on long-term value and empowering insiders to repel takeover attempts. As *148 Professor Gompers explains, “The other forms of anti-takeover protection - poison pills, staggered boards, golden parachutes - are no match for the power of dual-class stock.”20 Antitrust Analysis. The insiders at MasterCard - i.e., the member banks - found themselves in an unusual situation: they wanted to shed control, not harbor it. Most of MasterCard’s antitrust problems stem from the fact that the member banks act jointly, through MasterCard, when they set interchange fees and other network policies. 21 Bringing in a few public minority shareholders might not have been enough to change the antitrust analysis, as the member banks would still jointly control the venture in any meaningful sense. Even if more than half the shares were owned by the public, the biggest block shareholders (JP Morgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, HSBC) would still be in a strong position to control the company. To change the antitrust analysis, then, the member banks really had to give up control, or at least control over setting interchange fees and other policies that may have anti-competitive effects. With voting rights limited to the Class M rights over major transactions, it becomes much more difficult to say that the member banks are liable under a per se rule or even under the rule of reason. Consider the reasoning of United States v. Visa U.S.A., where the Second Circuit, applying the rule of reason, held illegal the practice of brand exclusion, the policy that prohibited banks that were members of MasterCard or Visa from issuing the cards of competitors, such as Discover or American Express.22 The defendants argued that brand exclusion was like Pepsi’s exclusive arrangement with its bottlers, which can hardly be said to prevent Coke from getting its product to market. The court dismissed this analogy: “The basic flaw in the analogy is that it depicts Visa U.S.A. (or MasterCard) as a single entity (like Coca-Cola) demanding a restrictive provision in its contract with a supplier of services to it. Visa U.S.A. and MasterCard, however, are not single entities; they are consortiums of competitors.”23 *149 The restrictive provision, the court concluded, “is a horizontal restraint adopted by 20,000 competitors.”24 The court went so far as to call such arrangements “exemplars of the type of anti-competitive behavior prohibited by the Sherman Act.”25 The obvious implication is that converting from a consortium of competitors to a single entity will help in future antitrust litigation. MasterCard faces an immediate threat in pending litigation over interchange fees. The legality of interchange fees was upheld in a 1986 case, National Bancard Corp. v. VISA U.S.A.26 In NaBanco, the Eleventh Circuit upheld the collective determination of interchange fees under the rule of reason. In doing so, the court defined the relevant market to include all payment methods, such as cash, checks, and debit cards in addition to credit cards. 27 It seems unlikely that a future court would define the relevant market in the same way, thus opening up MasterCard to liability. If MasterCard is legally viewed © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 5 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... as a single independent entity, however, it becomes more difficult (at least going forward) to find anti-competitive collective action or collusion among the banks. Whatever the organizational structure, MasterCard may still be liable for monopolistic behavior that violates Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act. With the member banks shedding effective control, however, MasterCard’s market power must be analyzed alone (and not aggregated with Visa), and its market share of roughly 30% should not give rise to Section 2 liability. The IPO structure, in sum, allows MasterCard to buy itself immunity from future lawsuits over interchange fees. Better yet, I suspect it effectively reduces liability for past behavior. By the time pending litigation is resolved, MasterCard will be an independent entity, and it may have been so for quite some time. By that time, the lawsuits over interchange fees may feel a little like suing Microsoft in a post-Google world. The action will have moved on.28 Regulators and judges, in particular, may lose some zeal once it becomes clear that things have changed, even if logically this is no excuse for illegal behavior in the past. *150 Dual-Class vs. Selling More. For regulatory reasons, then, it made sense for the member banks to shed control of MasterCard, and the dual-class structure accomplishes this regulatory goal. A more direct way to accomplish this regulatory result would be to simply sell the entire company to the public in the IPO, or perhaps to sell the firm outright to a financial buyer. This solution to the antitrust problem, however, would send a negative signal to prospective buyers: if the company is so great, then why are the insiders fleeing? Moreover, the member banks have built up the MasterCard network, and most appear to be genuinely bullish on its economic prospects. The intriguing solution, then, is the reverse dual-class structure. This allows the member banks to give up effective day-to-day control of the enterprise, thereby reducing antitrust exposure. At the same time, the member banks retain a large amount of the economics of the firm, thereby sending a positive signal to prospective investors and maximizing the sales proceeds in the IPO. Standing alone, the reverse dual-class structure would leave the company vulnerable to the influence of large shareholders, such as hedge funds, who may focus more on the short-term and medium-term value of the firm.29 It is said that such shareholders may push for reforms that boost the share price in the short-run but erode long-term value, or may destroy value by squabbling amongst themselves.30 Like shark attacks or the bird flu, however, this concern about value-destroying hedge funds seems to draw an inordinate amount of attention. Whether sensible or not, the deal effectively addresses this concern through another legal tool: the charitable foundation. III. The MasterCard Foundation In creating the Foundation, MasterCard is giving away about $600 million in value. This is, by any measure outside the philanthropic realm of Buffett and Gates, a large amount of money. Yet the *151 structure of the Foundation reveals that its goals are more instrumental than altruistic. The Foundation performs some important corporate governance functions. It will serve as block shareholder with a long-term view. Because the Foundation cannot sell its shares for twenty-one years, its trustees will have a single-minded focus on increasing the long-term share value. It has no reason to prefer large shareholders over small ones - or, more to the point, larger banks over smaller ones. The Foundation ensures that the network itself will carry an independent voice. The Foundation, as noted above, will hold 17% of the voting rights of the company, more than any other current or future shareholder. In addition to the Class A shares, MasterCard will fund the Foundation with approximately $40 million in cash over the first four years of its operations. 31 As noted above, the five initial directors of the Foundation will be selected by a “blue-ribbon” panel, which is itself selected by the current CEO, Robert Selander, the Chairman of the Board and representative of European banks, Baldomero Falcones Jaquotot, and one other current director. Thereafter, the continuing directors will appoint successors in consultation with MasterCard’s Nominating and Corporate Governance Committees. Absent branding concerns, the simpler way to accomplish the desired corporate governance ends might be to organize a grantor trust that would hold on to the stock for twenty-one years, with the trustees appointed by the member banks. You could imagine calling this the Insider Advantage Trust, the Anti-Competitive Trust, or the Repel-the-Hedge-Funds Trust. Calling it the MasterCard Charitable Foundation obviously has a better ring to it, both for regulators and consumers. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 6 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... Why Canada? Why choose to organize the Foundation in Canada? Canadian tax law is somewhat more lenient than U.S. tax law. In the U.S., foundations must spend 5% of their assets a year; in Canada, the requirement is 3.5%. As it is, MasterCard anticipates having to infuse another $40 million in cash to meet this requirement; another $15 million or more might be required to meet the U.S. standards. Moreover, MasterCard has applied to the Canadian tax authorities to seek a waiver of this requirement for up to ten years; the IRS would not have the authority to grant such a waiver. 32 *152 Fifteen million dollars is a small amount compared to the roughly $600 million in value MasterCard is giving away to the Foundation. Another compelling reason for choosing Canada may be to reduce litigation risk. If the Foundation were organized in the United States, the IRS could challenge whether the Foundation exclusively serves a charitable purpose, as required by the Internal Revenue Code. Or a state regulator - think someone like Eliot Spitzer - could challenge whether the Foundation serves a charitable purpose as required by state nonprofit law. While Canadian law also requires a charitable purpose, its less litigious environment seems more welcoming. The charitable foundation, in other words, reflects not just branding concerns but also some careful regulatory cost engineering. Charitable Purpose. The Foundation’s charitable purpose is somewhat vague, and the fit between MasterCard’s commercial identity and its role as corporate philanthropist is uneasy. MasterCard explains that the Foundation will “support programs and initiatives that help children and youth to access education, understand and utilize technology and develop the skills necessary to succeed in a diverse and global workforce.”33 MasterCard’s connection to education is weak; at best, perhaps it could be said that educated people are more likely to enter the consumer class and rely on non-cash payment systems. MasterCard explains further that “the Foundation will support organizations that provide microfinance programs and services to financially disadvantaged persons and communities in order to enhance local economies and develop entrepreneurs.”34 Microfinance, a trendy topic among academics, arguably relates more closely to MasterCard’s business. The Charitable Fit. Corporate charitable giving is easily attacked as a waste of shareholder value. It is most defensible where there is a strong fit between the corporate enterprise and the charitable cause, ensuring a strong branding effect. Consider Ben & Jerry’s. Ben & Jerry’s created the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation in 1985 to give away money to grassroots organizations addressing environmental and community problems. The fit with Ben & Jerry’s brand image of environmentally-sensitive localism is clear. Or Whole Foods, which recently created the Animal Compassion Foundation, catering to bobos who want to love their lobsters and eat them too. In these *153 cases, the charitable giving reinforces the valuable brand image in the minds of consumers. Here, the branding potential is powerful - $600 million is a lot of money to give away - but the fit is unclear. MasterCard’s stated charitable purposes relate to education and microfinance. The strongest case to be made is that the MasterCard brand image includes access to the upper middle class lifestyle: education and microfinance are both associated with upward class mobility. By giving money to such causes, MasterCard can enhance its brand image as a facilitator of the Priceless lifestyle (and create a few new MasterCard customers in the process). By shackling the Foundation’s ability to give for four years, however, the brand impact is muted. To the extent the public notices the Foundation at all, they may notice it for the corporate governance gimmick that it is rather than the social institution that it may become. European-Style Corporate Governance. The idea for using a charitable foundation came from the European banks. Combined with the board-within-a-board feature, placing the directors of the charitable foundation in control of MasterCard means that the U.S. banks will have little control over European operations. “A common sentiment in Europe,” writes one reporter, “particularly among French and German banks and within the European Commission, is that European institutions must not be governed by U.S. organizations . . .”35 The European board will maintain control over membership applications, fines, intraregional operating rules, fees, and rules for co-branding cards in Europe. Beyond the desire for European autonomy, the governance design reflects other managerial influences from Europe, where having a charitable foundation as a major shareholder is more common than in the United States. In particular, the commercial foundations in Norway, the industrial foundations in Sweden, and the family foundations in Liechtenstein, Switzerland, and Germany all tend to blur the line between charity and profit. 36 In Sweden, foundations own a controlling interest in IKEA; in Denmark, foundations control the Carlsberg brewery. 37 In Italy, where banking institutions had been *154 operated as nonprofits for many years, banking institutions were split into two parts: a new for-profit bank and a nonprofit foundation, which serve as majority shareholders of the new banks and concentrate on charitable, social, and welfare activities.38 At the extreme, as with the Wilsdorf Foundation-controlled Rolex watch company, the foundation maintains outright control of the for-profit operating company.39 © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 7 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... Having a foundation as a major shareholder increases managerial slack, reduces accountability, and encourages stakeholder-oriented thinking. In the U.S., managers are very sensitive to earnings. Corporate law is responding to pressure from shareholders, the SEC, and academics pushing for increased shareholder accountability. Shareholder primacy is the dominant norm in theory if not in practice. Europeans, by contrast, tend to value stability and sustainability. With its dominant shareholder position and twenty-one year lock-up, the Foundation gives MasterCard an undeniable European flair. IV. The Lawyer as Regulatory Wizard and Brand Image Designer The European taste for complex governance structures bodes well for the lawyering profession. Consider a recent article in The Economist magazine, which investigated the complicated structure of IKEA. 40 IKEA is indirectly owned by a Dutch Stichting (a nonprofit foundation), which itself is controlled by IKEA’s founder, Ingvar Kamprad, and his successors and heirs. The foundation is nominally devoted to encouraging innovation in interior and architectural design, but like the MasterCard Foundation, its outlays are rather stingy. Under Dutch law, the foundation’s charter locks in the structure and direction of the company, along with the influence of Kamprad and his successors. By locating the key intellectual property assets offshore, the Kamprad family siphons off significant profits through shell companies in Luxembourg, the Netherlands Antilles, and a trust in Curacao. The structure minimizes tax and disclosure *155 obligations while apparently doing little damage to IKEA’s brand image. Likewise the MasterCard deal - with its multiple classes of shares, the Canadian charitable foundation, multiple lock-ups, the European board-within-a-board, its management of regulatory costs, and its overall finesse - displays legal infrastructure being deployed in a variety of creative, even elegant ways. No one could seriously argue that the lawyers here were merely monkey scribes. Moreover, the structure of this deal shows that lawyers do more than manage regulatory costs, engineer transaction costs, and negotiate contracts to allocate risk to the least-cost avoider. Lawyers help shape the image of the company. The increasingly complex and creative structures of legal contracts must speak to multiple audiences: counterparties, investors, regulators, judges, consumers, employees. My one quibble with the lawyering here is that they might have done more to speak to consumers. The charitable foundation might just be too clever by half. Consumers may or may not catch on to the fact that the Foundation, its coffers stuffed with MasterCard stock, will actually give away very little. But even if this clever bit of regulatory cost engineering does not damage the brand, it represents a missed opportunity to enhance the brand image. As one of my UCLA students pointed out, imagine the goodwill MasterCard could have generated if the MasterCard Foundation, rather than FEMA, had given away $1000 debit cards to Hurricane Katrina victims. The Foundation’s stingy structure also opens its flank to attack on regulatory grounds, as antitrust plaintiffs will argue that the Foundation is merely a ruse, and that the member banks will maintain control from behind the glass doors of the Foundation. I don’t think such an attack would ultimately succeed in court, but the allegations could needlessly tarnish an otherwise elegant deal. With its long lock-up and miserly spending limitations, the Foundation’s structure dismisses not just a philanthropic opportunity but an opportunity to create new customers for MasterCard. My broader point here is that foundations and nonprofit organizations are legal tools that, like other contractual arrangements, may serve whatever purposes their masters intend. Like special purpose vehicles, staggered boards, or embedded anti-takeover devices, these legal tools can be used for purposes both good and bad. Consider the accounting/economics arbitrage with Enron’s SPVs, or the tax/economics arbitrage of KPMG’s tax shelters, or the tax/economics arbitrage of the Stanley Works reincorporation in Bermuda. When *156 lawyers encourage or allow their clients to push the regulatory arbitrage to the extreme, their impressive legal maneuvering can ultimately hurt the client. Hubris does not enhance the brand. We are a long way from a comprehensive theory of understanding all the tasks that lawyers can and should perform; my hope is that qualitative empirical studies like the ones in this symposium provide some useful data points to help us develop theories that may later be tested quantitatively. V. Conclusion This case study analyzed the legal infrastructure of the MasterCard IPO. I argued that the goal of the deal’s design was both to reduce antitrust exposure and enhance the company’s image as a safe, secure brand that facilitates a middle-class consumer lifestyle. Lawyers played a central role in accomplishing these goals. First, they designed an unusual “reverse” dual-class voting structure, which allowed the member banks to reduce their formal control over the firm while maintaining a © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 8 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... significant economic stake. Second, they designed a charitable foundation to serve as a powerful corporate governance device, as well as to potentially serve altruistic ends. Footnotes << pi> > Associate Professor, University of Colorado School of Law. I thank Guhan Subramanian, Michael Simkovic, and Crystal Blum for their efforts in putting this conference together. I am also indebted to my students in my Fall 2005 Deals class at Georgetown University Law Center for their input on this case study. For helpful discussions and comments on the project, I thank Kenneth Basin, Colin Daniels, Mark Fenster, Laura Heymann, Michael Klausner, Scott Peppet, Miranda Perry, Steve Salop, Susan Scafidi, Gordon Smith, Ethan Stone, Guhan Subramanian, and Josh Wright. I also thank Steve Hurdle and Michael Ingrassia for their wonderful research assistance. On why this is a “pi” footnote instead of a “star” footnote, see Victor Fleischer, Brand New Deal: The Branding Effect of Corporate Deal Structures, 104 Mich. L. Rev. 1581, 1602 (2006) (discussing the building numbers at Google’s headquarters and nerd signaling more generally). See generally Charles A. Sullivan, The Under-Theorized Asterisk Footnote, 93 Geo. L.J. 1093 (2005). 1 Deal structures are generally driven by a desire to manage transaction costs. See generally Ronald J. Gilson, Value Creation by Business Lawyers: Legal Skills and Asset Pricing, 94 Yale L.J. 239 (1984). I explore the branding implications of deal structures in more detail in Fleischer, supra note <<pi>>. 2 On dual-class firms, see generally Paul A. Gompers, Joy Ishii & Andrew Metrick, Extreme Governance: An Analysis of Dual-Class Companies in the United States, AFA 2005 Philadelphia Meetings (Am. Fin. Ass’n, Berkeley, Cal.), Mar. 2006. 3 MasterCard simply could have written a check to any of the charitable organizations it wants to support. If, in addition to cash assistance, MasterCard wanted to establish a separate institution with greater assets and lasting impact, it could have funded the foundation with stock and freed it to sell stock as needed to provide donations to worthy recipients in the future. 4 The charter prevents any other shareholder from accumulating more than the 15% of the shares that the Foundation holds. It’s possible (though unlikely, for reasons I discuss below) that the Foundation’s trustees could become unhappy with MasterCard’s management and join forces with a takeover consortium. 5 Stock-holding charitable foundations are more common in Europe, where shareholder primacy norms are less entrenched. See infra notes 36-39. 6 See James B. Kelleher, Lifting the Lid: In MasterCard IPO, a Charity’s Role Questioned, Reuters, Dec. 22, 2005. 7 See Victor Fleischer, Posting to Conglomerate Blog, http:// www.theconglomerate.org/2006/03/monkey_scribes.html (Mar. 7, 2006). 8 This Section draws on the work of the students in my Deals class at the Georgetown University Law Center in the Fall of 2005. I am particularly indebted to the excellent paper prepared by Timothy Hauck, Michael Ingrassia, Daniel Knepper, William Mouat, and Geoffrey Thompson. This analysis is based on the deal’s preliminary filings made with the SEC in 2005. The deal was then delayed for several months. See MasterCard Inc., Amendment No. 2 to Registration Statement (Form S-1) (Dec. 5, 2005), availableat http:// www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1141391/000119312505237110/ds1a.htm. MasterCard’s CEO, Robert Selander, disclosed in February 2006 that he was recovering from prostate cancer surgery, and that the road show would have to be postponed. See Liz Moyer, Selander Cites Health, Puts Off MasterCard IPO, Forbes.com, Feb. 16, 2006, http:// www.forbes.com/facesinthenews/2006/02/16/mastercard-ceo-ipo-cx_lm_ 0216autofacescan13.html. The IPO was conducted in May 2006; to my knowledge none of the significant features of the deal structure were changed in the interim. 9 See Yoram Barzel, Michel A. Habib, & D. Bruce Johnsen, Prevention is Better than Cure: Precluding Information Acquisition in © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 9 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... IPOs, 79 U. Chi. J. Bus. (forthcoming 2006), available at http:// fic.wharton.upenn.edu/fic/papers/04/p0413.html. 10 See Fleischer, supra note <<pi>>. 11 See Top Card Brands are in a League of Their Own, Am. Banker, Aug. 12, 1997, at 16. See also Timothy Hauck, Michael Ingrassia, Daniel Knepper, William Mouat & Geoffrey Thompson, The MasterCard, Inc. IPO, at 22 n.88 (2005) (unpublished case study, Deals: Engineering Financial Transactions Class, Georgetown University Law Center, on file with the author), available at http://spot.colorado.edu/~fleischv/Teaching/DealsFiles.html/MasterCard-Ingrassia.pdf. 12 See Kaitlin Quistgaard, MasterCard vs. Ralph http://www.salon.com/business/feature/2000/08/17/nader_mastercard/. 13 See MasterCard Brand Center, Acceptance Mark Uses, http:// www.mastercardbrandcenter.com/mcbrand/us/howtouse.do?pageId=htuob_amu_home (last visited Oct. 18, 2006). For example, the website explains: When using our brand names in communications that promote our brands, the brand name(s) always must be used at least once. The brand names must not appear in all uppercase or all lowercase letters and always must appear in English. In general, the MasterCard, MasterCard Electronic, Maestro, Mondex, and Cirrus brand names should be used as adjectives, as in ‘Your MasterCard card.’ At a minimum, the brand names must be used as adjectives in their first or most prominent mention subsequent to any use in the title, headline, signature, or cover page of a communication, and include the ® and/or ™ trademark symbols as designated for each. 14 See Adam J. Levitin, The Antitrust Super Bowl: America’s Payment Systems, No-Surcharge Rules, and the Hidden Costs of Credit, 3 Berkeley Bus. L.J. 265 (2005). 15 See id. 16 Frequent-flier miles and other rewards programs make matters worse by encouraging consumers to use credit cards over other forms of payments; as merchants hike up prices to pay high interchange fees, which in turn allow issuing banks to give back rewards, the biggest losers are cash-paying customers, who pay higher prices without getting either the convenience of paying on credit or the kickback of frequent flier miles or other rewards. 17 See infra p. 146 (discussion of board-within-a-board structure). 18 See MasterCard, Inc., Registration Statement (Form S-1/A), at 145 (May 23, 2006). 19 Because member banks cannot hold Class A shares, the conversion is accomplished by holding the shares in escrow before they are sold directly to the public in exchange for cash. The conversion right, in other words, is really a right to sell the stock. 20 Gompers, supra note 2, at 1-2. 21 See generally Dennis W. Carlton & Alan S. Frankel, The Antitrust Economics of Credit Card Networks, 63 Antitrust L.J. 643 (1995); David S. Evans & Richard Schmalensee, Economic Aspects of Payment Card Systems and Antitrust Policy Toward Joint Ventures, 63 Antitrust L.J. 861 (1995). On the international implications, see Avril McKean Dieser, Antitrust Implications of the Credit Card Interchange Fee and an International Survey, 17 Loy. Consumer L. Rev. 451 (2005). Nader, Salon.com, © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. Aug. 17, 2000, 10 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... 22 United States v. Visa U.S.A., 344 F.3d 229 (2d Cir. 2003). 23 Id. at 242. 24 Id. 25 Id. 26 National Bancard Corp. v. VISA U.S.A., 779 F.2d 592 (11th Cir. 1986). 27 Id. at 603. 28 See generally Adam J. Levitin, The Merchant-Bank Struggle for Control of Payment Systems, 17 J. Fin. Transformation 73 (2006) (discussing the diminishing threat of antitrust litigation in the payments industry as independent payments networks split from large banks and technology and Internet commerce continue to develop). 29 On the conflict between current and future shareholders, see generally Jesse M. Fried, Corporate Law’s Current-Owner Bias 1-77 (Berkeley Program in Law & Econ., Working Paper Series, Paper No. 181, 2006), http:// repositories.cdlib.org/blewp/art181/. 30 See, e.g., Iman Anabtawi, Some Skepticism About Increasing Shareholder Power, 53 UCLA L. Rev. 561 (2006). I am not persuaded that the markets are so inefficient that hedge funds could systematically increase short-term stock prices while simultaneously eroding long-term value. If anything, recent history has shown management, not shareholders, to be adept at using fraudulent accounting to accomplish this particular trick. Nonetheless, aggressive hedge funds are a concern that seems to occupy much managerial attention. 31 See MasterCard, Inc., Definitive Proxy Statement (Schedule 14A), at 8 (Oct. 26, 2005). 32 I am indebted to Professor Ethan Stone for this insight. 33 Definitive Proxy Statement, supra note 31, at 9. 34 Id. 35 “... Except in Europe,” CardLine, Sept. 23, 2005, at 1. 36 See Helmut K. Anheier, Foundations in Europe: a Comparative Perspective, in Foundations in Europe: Society, Management & Law 35, 46 (Andreas Schülter, Volker Then & Peter Walkenhorst eds., 2001). 37 See Joel L. Fleishman, Public Policy and Philanthropic Purpose - Foundation Ownership and Control of Corporations in Germany and the United States, in Foundations in Europe: Society, Management & Law, supra note 36, at 372, 381-82 (citing numerous other examples of foundation-controlled corporations). © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 11 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 9/20/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MASTERCARD IPO: PROTECTING THE PRICELESS..., 12 Harv. Negot. L.... 38 See Gian Paolo Barbetta & Marco Demarie, Italy, in Foundations in Europe: Society, Management & Law, supra note 36, at 166. See also Henry Hansmann, The Ownership of Enterprise 246-64 (1996) (discussing how nonprofits financial institutions developed historically in response to opportunism concerns). 39 See Martin Steinert, Switzerland, in Foundations in Europe: Society, Management & Law, supra note 36, at 247, 249 & n.11. 40 See Flat-Pack Accounting, The Economist, May 13, 2006, at 76. End of Document © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 12