Chapter 4 - Thorsteinssons LLP Tax Lawyers

advertisement

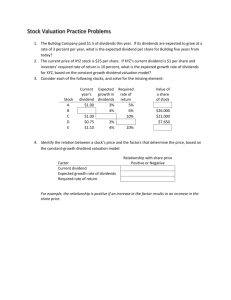

Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes Chapter Four Lecture Notes Special Refundable Tax System For Investment Income of Certain Private Corporations David Christian Spring Term 2013 Thorsteinssons LLP UBC Faculty of Law ______________________________________________________________________________ Notes In my own case the words of such an act as the Income Tax, for example, merely dance before my eyes in meaningless procession – cross-reference to cross-reference, exception upon exception – couched in abstract terms that offer no handle to seize hold of – leave in my mind only a confused sense of some vitally important, but successfully concealed, purport, which it is my duty to extract, but which is within my power, if at all, only after the most inordinate expenditure of time. Hand J. 1. The focus of this Chapter is on a special refundable tax system at the corporate level, which is fundamentally designed to: prevent deferral of tax by earning the investment income inside a corporation; and permit integration of tax when comparing the earning of investment income personally or inside a corporation. The Chapter will look at two types of special taxes on “investment income” and will examine the “refundable nature” of these taxes. The investment income in this context consists of two broad categories: (i) all investment income except dividends received from other Canadian corporations, and (ii) dividends received from other Canadian corporations. The refund of the tax imposed on these two categories of investment income is handled through a mechanism that is referred to as the “RDTOH account”. The name will become clear below. Dividends paid by a certain type of corporation that earns this investment income, and pays the special taxes on the investment income, will trigger a refund of tax to the Page 110 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes corporation. The RDTOH account is a method of tracking the amount of tax the corporation can potentially get refunded to it upon payment of sufficient dividends by that corporation. This Chapter will also look at how the corporate tax system deals with the one half tax-free portion of capital gains realized by a CCPC. Investment Income Except Dividends from Other Canadian Corporations 2. This scheme imposes a special tax on the “aggregate investment income” of a Canadian-controlled private corporation (CCPC). We are familiar with the legal concept of a CCPC. What is captured by “aggregate investment income”? Read the definition of that term in subsection 129(4). This consists of the following net income amounts: The amount, if any, by which the “eligible portion” of the corporation's taxable capital gains for the year exceeds the total of (i) the eligible portion of its allowable capital losses for the year and (ii) net capital losses for other taxation years deducted in the year (paragraph (a)). The corporation's “income for the year from a source that is a property” other than the portion of any dividend from another Canadian corporation that was deductible under section 112 in computing the corporation's taxable income for the year (paragraph (b)). (Dividends from other corporations are subject to the other special refundable “Part IV” tax below.) 3. The “eligible portion” of a taxable capital gain is defined in subsection 129(4) as the portion of a taxable capital gain (or allowable capital loss, as the case may be) of the CCPC for the year from a disposition of a property that cannot reasonably be regarded as having accrued while the property was held by a non-CCPC. How could the latter arise? 4. What constitutes “income from a source that is a property”? Recall the concept of “income from property” in Tax I? Krishna describes it this way: Page 111 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes Generally, income from property is the investment yield on an asset. Rent, dividends, interest, and royalties are typical examples. We earn the yield on the investment by a relatively passive process. For example, where an individual invests in land, stocks, bonds, or intangible property, and collects investment income therefrom without doing much more than holding the property, the income is … income from property. 5. Remember Chapter 3 and the notion of a “specified investment business”? Income from that business did not qualify as an “active business” of a CCPC. Now read the definition of “income from a source that is a property” in subsection 129(4). You specifically include as this type of income the income from a specified investment business carried on by the CCPC in Canada (paragraph (a)). Consider some examples (rental apartment building, franchising business, investing in second tier mortgage financing, etc.). You specifically exclude from this type of income: o the income from any property that is incident to or pertains to an active business carried on by the CCPC, and o the income from any property that is used or held principally for the purpose of gaining or producing income from an active business carried on by it. 6. Read the decision in Shamita Inc. v. The Queen (copy enclosed with these materials). 7. What tax rate applies to a CCPC’s “aggregate investment income” and how does the refundable portion of that tax work? Remember Chapter 1, where we said the “base case” tax rate on a corporation’s income was as follows. “Base case” tax rate to be applied to the corporation’s taxable income to arrive at the tax owing by the corporation start with (historical) federal tax rate % Section references and notes 38 123(1)(a) - most recent, but still historical, base federal rate Page 112 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes 8. subtract the federal “general rate reduction” 13 subtract the “provincial abatement” 10 add the base case provincial tax rate on the corporation’s income earned in the province 10 thus, the total tax “base case” tax rate on the corporation’s taxable income in Canada is 25 123.4(2) - this gives us the current base federal rate of 25% before making “room” for the provincial and territorial taxes - assume here the corporation’s income is basic “full rate taxable” income 124(1) – makes “room” for the provinces and territories to impose their own tax rate on the corporation’s “taxable income earned in a province” – this gives us the net current federal rate of 15% where the corporation’s income is subject to provincial or territorial tax the provincial rate here is the base rate of 10% in subsection 14(2) Income Tax Act (British Columbia) the base corporate tax will vary across Canada as provinces and territories impose tax at rates different from British Columbia Recall in Chapter 3 the “base case” is modified where the corporation is a CCPC and the income is “active business income” under $500,000. The “base case” is also modified where the corporation is a CCPC and the income is “aggregate investment income”. In this event, the corporate tax rate that applies to the aggregate investment income is built as follows. start with initial base federal tax rate general federal rate reduction 38 123(1)(a) - most recent, but still historical, base federal rate. 0 Read paragraph (b)(iii) of the definition of “full-rate taxable income” in 123.4(1), which backsout of the income qualifying for the general rate reduction a CCPC’s “aggregate investment income”. Page 113 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes subtract the “provincial abatement” add the special tax provincial tax Total initial corporate tax on a CCPC’s aggregate investment income (10) 124(1) – recall this makes “room” for the provinces and territories to impose their own tax rate on the corporation’s “taxable income earned in a province” – this gives us the net current federal rate of 28% before the “special” additional tax on aggregate investment income. 6.67 123.3 - this is the special additional tax applies to a CCPC’s aggregate investment income. This gives us the net federal rate of 34.67% - 10 the general corporate rate in British Columbia. 44.67 Note: This is the tax rate before any refund out of the RDTOH account below. The object of adding the refundable tax is that there be “no deferral of tax” on investment income earned by a corporation. Imagine an individual who would otherwise earn aggregate investment income personally. The personal tax rate (top rate) in British Columbia we saw from Chapter 1 is 43.7%. If that same income is earned inside a CCPC, the tax rate applicable to that income is 44.67%. There is certainly no deferral advantage gained by earning the aggregate investment income inside the CCPC. In fact, there is a 0.97% disadvantage to earning the income inside a CCPC. 9. This is not the end of the tax system for a CCPC’s aggregate investment income. Turn to the rules for a “refund” of some of the 44.67% tax paid by the CCPC as shown above. Read subparagraphs 129(1)(a)(i) and (ii). When a tax return is filed for a year, the Minister refunds to the CCPC (actually any private corporation – which will become relevant for Part IV tax below as well) an amount equal to the lower of two amounts: 1/3rd of all taxable dividends paid by the CCPC in the year; and the CCPC’s “refundable dividend tax on hand account” (RDTOH account for short) at the end of the year. Page 114 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes The amount refunded to the CCPC is called the “dividend refund” for the year. 10. The foregoing leads to the question: What amounts are in a CCPC’s RDTOH account at the end of a current year? Read subsection 129(3). The CCPC’s RDTOH account at the end of a current year means: The amount by which the total of: 26 2/3% of the CCPC’s aggregate investment income for the current year (paragraph a), and the taxes payable under Part IV for the current year on dividends from other corporations (discussed below), and the CCPC’s RDTOH account at the end of the preceding year exceeds: 11. the CCPC’s dividend refund for its preceding year. How does this look numerically? (slowly). Walk through the following chart CCPC $ 1. 2. 3. CCPC’s aggregate investment income in year one is Individual Shareholder Recipient of Dividend $ Paid to and refunded by the Government 100 CCPC’s tax paid on its aggregate investment income in year one as determined above is 44.67 CCPC’s remainder, say, cash in the bank is 55.33 44.67 Page 115 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. CCPC’s RDTOH account at the end of year one – 26.67% of its aggregate investment income in year one (assume no Part IV tax or prior year RDTOH). Note, this is an asset of the CCPC because the government must refund it upon payment of sufficient dividends by the CCPC. 26.67 Assume the CCPC pays a taxable dividend of $82.00 (sum of cash and RDTOH) in year two – which is included in the shareholder’s income in year two under 82(1)(a). The payment of the dividend in year two allows the CCPC to claim a refund under 129(1)(a) equal to the lower of (i) 1/3rd of the dividend and (ii) its RDTOH at the end of year two – assume the RDTOH has remained at 26.67 at the end of year two for simplicity. The CCPC’s net tax paid on the aggregate invesment income is thus the initial tax less the amount refunded to it (44.67 – 26.67 = 18.00). The individual shareholder must include the additional “gross-up” amount in income equal to ¼ of the dividend paid under 82(1)(b). 82.00 26.67 18.00 18.00 20.50 The individual shareholder’s total income is 102.50 10. The individual’s tax at the top rate of 43.7% (recall from Chapter 1) is 44.79 11. The shareholder is entitled to the dividend tax credit, which from Chapter 1 was 83.67% of the gross-up amount. 17.15 12. The individual shareholder’s net tax is 27.64 9. 13. Total net tax paid by CCPC and individual shareholder is 27.64 45.64 In broad tax policy terms, the dual objective of this special system for taxing a CCPC’s “aggregate investment income” is (i) to prevent the deferral of taxation by earning the income inside a CCPC (which is accomplished by, effectively, requiring the prepayment of shareholder distribution tax), and (ii) to achieve a very rough integration of tax when dividends are paid out of the CCPC. Notice, the net tax rate inside the CCPC, after the refund of a portion of the tax initially paid on the aggregate investment income, is roughly the 20% corporate tax rate that, in policy terms, was the basis for the “gross-up and dividend tax credit” Page 116 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes system seen in Chapter 1, which is designed in policy terms to avoid double taxation. Of course, there are variations from year-to-year in the initial corporate tax rate and the total tax paid on the aggregate investment income. The variations arise as the corporate and personal tax rates are changed at both the federal and provincial levels. Compare the top personal rate on aggregate investment income in British Columbia (43.7%) with the initial tax rate inside the CCPC (44.67%) and the total tax paid by the CCPC and the individual shareholder (45.64%). As matters currently stand, there is no deferral advantage (in fact, in our example there is a slight initial cost of 0.97%) and perfect integration is not achieved (in fact, there is a slight absolute cost of 1.94%). 12. Recall one point from Chapter 3. Certain income that would otherwise qualify as a CCPC’s “income from a source that is property”, and would thus otherwise be subject to the refundable tax system above, is deemed instead to be the CCPC’s “active business income” in cases described in subsection 129(6). Read subsection 129(6), which is sometimes called the “source preservation rule” for associated CCPCs. Recall the examples: Mr. X “associated”” CCPC 1 CCPC 2 loan active business interest The interest income is deemed to be “active business income” to CCPC 2 Page 117 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes Mr. X “associated” CCPC 1 dental business CCPC 2 lease building rent The rental income is deemed to be active business of CCPC 2 income. The interest income and the rental income would in the first instance be “aggregate investment income” of CCPC 2. However, that income (paid by associated CCPC 1 to CCPC 2) is deemed not to be part of its aggregate investment income if the amount was deducted in computing the “active business income” of the associated CCPC 1. The apparent policy is that one should not be allowed to “convert” what is fundamentally active business income (in CCPC 1) into aggregate investment income in CCPC 2 by the mechanism of having two CCPCs. Some commentators view this as making sure that the rough integration system for aggregate investment income cannot, indirectly, be superimposed on active business income of a CCPC that could, in theory, exceed the $500,000 small business limit. This policy objective has been rendered irrelevant by the introduction of the enhanced dividend tax credit. In fact, one would now seek to have property income converted to active business income, as it defers 19.67% of corporate tax. Private Corporations that Receive Dividends from other Canadian Corporations 13. Recall that excluded from aggregate investment income is “… the portion of any dividend from another Canadian corporation that was deductible under section 112 in computing the corporation's taxable income for the year”. Because such dividends are deductible in computing a corporate shareholder’s ordinary income under Part I of the Act, such dividends are not subject to any tax at all under Part I of the Act Page 118 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes 14. This potential to receive tax free dividends under Part I of the Act has spawned a number of separate and distinct rules that we examine throughout the course. The first set of such rules we look at is called the refundable Part IV tax, which is payable by private companies (and a very limited subset of other companies) on certain dividend income received from other Canadian companies. In order to understand the first main policy behind Part IV tax, we need to go back, once again, to some basic points made in Chapter 1. 15. Consider an individual shareholder that invests in shares of a Canadian corporation. Apply what you know now and determine the “effective tax rate” focusing only on the actual dividend received by the individual and the tax paid on that actual dividend. How? We have “run” the tax system for (i) the “base rate” for all corporations, (ii) the “small business rate” for CCPC active business income, and (iii) the refundable tax system for CCPC aggregate investment income. In each case we looked at the total tax paid by the corporation and the individual shareholder. For ease of reference these charts appear below assuming the corporation’s income is $100 in each case. Page 119 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes Base Rate Case the corporation’s tax on $100 of income at the base rate of 25% is the actual dividend paid to the individual shareholder “gross-up” the dividend by 38% of the dividend $25.00 $75.00 $28.50 shareholder tax at the top federal-provincial tax rate of 43.7% $45.23 deduct the enhanced “dividend tax credit”, being 89.99% of the gross-up, $25.65 net shareholder tax $19.58 the total $44.58 of tax on $100 of income translates to an effective tax rate of 44.58%, or rounded to 45% Small Business Rate Case tax at the small business rate (13.5%) 13.50 after-tax dividend to the individual shareholder 86.50 gross-up (1/4 of the dividend) 21.63 shareholder’s income 108.13 shareholder tax (43.7%) 47.25 dividend tax credit (83.67% of gross-up) 18.10 net shareholder tax 29.15 the total $42.65 of tax on $100 of income translates to an effective tax rate of 42.65%, or rounded to 43% Page 120 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes Refundable Aggregate Investment Income Case 1. CCPC’s aggregate investment income in year one is 100 CCPC’s tax paid on its aggregate investment income in year one as determined above is 44.67 3. CCPC’s remainder, say, cash in the bank is 55.33 4. CCPC’s RDTOH account at the end of year one – 26.67% of its aggregate investment income in year one (assume no Part IV tax or prior year RDTOH). Note, this is an asset of the CCPC because the government must refund it upon payment of sufficient dividends by the CCPC. 2. 5. 6. 7. 8. 26.67 Assume the CCPC pays a taxable dividend of $82.000 (sum of cash and RDTOH) in year two – which is included in the shareholder’s income in year two under 82(1)(a). The payment of the dividend in year two allows the CCPC to claim a refund under 129(1)(a) equal to the lower of (i) 1/3rd of the dividend and (ii) its RDTOH at the end of year two – assume the RDTOH has remained at 26.67 at the end of year two for simplicity. The CCPC’s net tax paid on the aggregate invesment income is thus the initial tax less the amount refunded to it (44.67 – 26.67 = 18.00). The individual shareholder must include the additional “gross-up” amount in income equal to ¼ of the dividend paid under 82(1)(b). 44.67 82.00 26.67 18.00 18.00 20.50 The individual shareholder’s total income is 102.50 10. The individual’s tax at the top rate, recall from Chapter 1 is 44.79 11. The shareholder is entitled to the dividend tax credit, which from Chapter 1 was 83.67% of the gross-up amount. 17.15 12. The individual shareholder’s net tax is 27.64 9. 13. Total net tax paid by CCPC and individual shareholder is 27.64 45.64 Page 121 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes Now answer the question posed. What is the “effective tax rate” on a dividend from a Canadian corporation received by an individual shareholder - focusing only on the actual dividend received by the individual and the actual tax paid on that actual dividend? In the base rate case the actual dividend was $75.00 and the actual tax paid by the shareholder was $19.58. The effective tax rate is thus 26.11%. In the small business rate case the actual dividend was $86.50 and the actual tax was $29.15. The effective tax rate is thus 33.7%. And finally, in aggregate investment income case the actual dividend was $82.00 and the actual tax was $27.64. The effective tax rate is thus 33.7%. The “effective tax rate” on a dividend received by an individual is the same on all income other than eligible dividends paid from income taxed at the top corporate tax rate (GRIP): 33.7%. It will become obvious why this is the case: the same variables apply to each dividend, namely the gross-up, the personal tax rate, and the dividend tax credit. The result is the same effective tax rate on the dividend in each case in which the variables are equal, regardless of what type of corporation is paying the dividend and what tax the corporation may or may not have paid. It is only when the variables are changed – by increasing the gross-up, and thus the dividend tax credit – that the shareholder tax is reduced. 16. Now consider the follow case. An individual wants to use excess funds to invest in shares of Telus or the Royal Bank (both Canadian corporations). It occurs to the individual that the funds could be invested in a private company. Ind’l Private Co. Publi c Telus (TSE) Publi c Royal Bank (TSE) Page 122 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes 17. Rather than pay 26.11% tax on any eligible dividends received by the individual personally (or 33.7% if the dividend is not an eligible dividend) the private company will receive them and get a the subsection 112(1) deduction so there is no Part I tax paid at all on the dividends. Admittedly, there will be a tax when the private company pays dividends to the individual, but not until that time. Thus, there is a potential for unlimited deferral of tax on dividends in this classic case. Enter Part IV tax. First Aspect of Part IV Tax (and the RDTOH Account - Again) 18. The above is one classic example to which the rules in Part IV (sections 186 to 186.2) are targeted. The first aspect of Part IV tax is to impose a 33.33% tax on the dividends received by the private corporation from certain Canadian corporations. 19. Read paragraph 186(1)(a) and all the related rules that apply to it. Subsection 186(1) applies the 33.33% Part IV tax to “assessable dividends” received by a “private corporation” or a “subject corporation”. The definition of a “private corporation” was reviewed in Chapter 2. The second type of corporation is defined in subsection 186(3), and includes the relatively rare case of a corporation (other than a private corporation) resident in Canada and controlled by, or for the benefit of, an individual (other than a trust), or a related group of individuals (other than trusts). Subsection 186(5) deems a subject corporation to be a private corporation for purposes of a refund out of the RDTOH account (described below). An “assessable dividend” is defined in subsection 186(3) as a taxable dividend that is deductible under subsection 112 in computing Part I income. This deduction is, of course, the reason for the existence of Part IV tax. Page 123 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes The rule in paragraph 186(1)(a) looks to whether the company paying the dividend to the private corporation, or subject corporation, is not “connected with” the private corporation or subject corporation. “Connected with” is a vitally important test and is defined in subsections 186(2) and (4). 20. 1 The corporations are “connected” where the paying corporation is “controlled” by the private corporation or subject corporation, or is so “controlled” by persons who “do not deal at arm’s length with” the private corporation or subject corporation – and note in this context that: (i) “controlled” means “owning more than 50% of payer corporation’s shares that have full voting rights under all circumstances, and (ii) persons are deemed not to deal at arm’s length with each other when they are “related” for tax purposes, a concept you will recall from Chapter 3 (read paragraph 251(1)(a)),1 The corporations are also “connected” where the private corporation or subject corporation owns shares of the paying corporation that represents: (i) more than 10% of shares having full voting rights under all circumstances, and (ii) more than 10% of the value of all shares of the payer corporation. The foregoing “connected corporation” tests are sometimes referred to as the “control test” and the “10% votes and value” test. Note these are alternate tests. However, all the Part IV tax in paragraph 186(1)(a) is refundable to the private corporation when that company pays taxable dividends. The refund mechanism is effected through the addition of Part IV tax to a private corporation’s RDTOH account, and the refund of tax is subject to There are other tests for “not dealing at arm’s length”, which we will look at later in the course. Those tests will also apply here. The “related person” test is most often encountered in this context. Page 124 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes the same limitations in paragraph 129(1)(a). Read paragraph 129(3) again. You add to the RDTOH account of a private corporation “the total of the taxes under Part IV payable by the corporation for the year”. Thus, the payment of a dividend by a private corporation will trigger a refund of tax out of the RDTOH account pursuant to subsection 129(1). Dividends received by Private Co Part IV tax paid (and addition to the RDTOH account) dividend paid by Private Co refund to the Private Co out its RDTOH account below, subject to the 129(1)(a) limit of 1/3rd of the dividend paid by the Private Co Private Co’s net tax on dividends received 100 (33.33) 100 33.33 0 The general object of this first aspect of Part IV tax is to prevent deferral of tax when you compare the situation of an individual receiving the dividends with a private corporation receiving the dividends. There is a very slight cost (0.37%) on dividends that are not eligible dividends, and a significant interim cost (8.28%) on eligible dividends. However, as most dividends subject to the first aspect of Part IV tax will be eligible dividends (as they will be paid by public corporations) the cost is a significant disincentive to a private corporation receiving eligible dividends. Second Aspect of Part IV Tax 21. This second aspect of Part IV tax operates to “preserve” the tax effect of a prior addition to the RDTOH account of a payer corporation that is connected with the private corporation that receives the dividend. This aspect ties-in both of the additions to the RDTOH account that we have seen thus far, namely, the 26.67% of a CCPC’s aggregate investment income and the Part IV itself. 22. This second aspect of Part IV tax in contained in paragraph 186(1)(b). The tax applies where the payer private corporation is connected with the receiving private corporation, and the dividend paid to the receiving Page 125 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes private corporation triggers a refund of tax to the underlying payer private corporation out of its RDTOH account. The amount of the Part IV tax is equal to the relative portion of the refund to the paying corporation, that relative portion being determined with reference to the amount of dividends paid by the paying corporation in the year. The precise language of paragraph 186(1)(b) is worth quoting here. The Part IV tax amount is equal to: “…all amounts, each of which is an amount in respect of an assessable dividend received by the particular [private] corporation in the year from a private corporation or a subject corporation that was a payer corporation connected with the particular [private] corporation, equal to that proportion of the payer corporation's dividend refund (within the meaning assigned by paragraph 129(1)(a)) for its taxation year in which it paid the dividend that: (i) the amount of the dividend received by the particular corporation is of (ii) 23. the total of all taxable dividends paid by the payer corporation in its taxation year in which it paid the dividend …” Consider one example applying paragraph 186(1)(b). Individual Privateco B Ltd. teco B Ltd. Privateco A Ltd. Apartment Building Page 126 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes Company Holdco 1. Privateco A Ltd’s rental income, being its “aggregate investment income” 100 2. Initial tax on Privateco A Ltd’s aggregate investment income 44.67 3. Addition to Privateco A Ltd’s RDTOH account 26.67 4. Dividend to Privateco B Ltd 5. Dividend refund to Privateco A Ltd under paragraph 129(1)(a) out of its RDTOH 6. Net tax paid by Privateco A Ltd 7. Part IV tax payable by connected Privateco B Ltd under under paragraph 186(1)(b) 26.67 8. Addition to Privateco B Ltd’s RDTOH account 26.67 9. Dividend to the individual shareholder of Privateco B Ltd Gov’t 44.67 82.00 26.67 18.00 26.67 82.00 10. Dividend refund to Privateco B Ltd under paragraph 129(1)(a) 26.67 11. Net tax paid by Privateco B Ltd Holdco tax – after refund 0 24. Ind’l Take another example as follows. Page 127 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes Individual Holdings Ltd. dividend Investments Ltd. Publi c dividend Telus dividend Publi c Royal Bank Investments Ltd. receives $100 in dividends from Telus and Royal Bank, and pays $33.33 Part IV tax under paragraph 186(1)(a) on dividends from Telus and Royal Bank. This amount is added to its RDTOH account. Investments Ltd. then pays a $100 dividend to Holdings Ltd. This payment of a $100 dividend generates a refund to Investments Ltd. equal to $33.33 out of its RDTOH account. Holdings Ltd. is “connected with” Investments Ltd. and the dividend it received generated a refund of Part IV tax to Investments Ltd. out of its RDTOH account. Accordingly Holdings Ltd. becomes liable to pay $33.33 of Part IV tax under paragraph 186(1)(b), and that amount is added to its RDTOH account, and so on.2 2 Note that if the initial dividends received are “eligible dividends”, they will be added to the GRIP of Investments Ltd. The dividend paid by Investments Ltd. will also be designated as an “eligible dividend”, and added to Holdings Ltd.’s GRIP. The designation is irrelevant to each corporation (as the dividend is deductible for purposes of Part I tax, and the designation has no effect on Holdings’ liability for Part IV tax) but preserves the ability of the individual shareholder to utilize the Page 128 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes The Capital Dividend Account – Tax Free Portion of Capital Gains 25. There is one last “integration” systems point. It is called the “Capital Dividend Account” (CDA). The essence is simply this: the untaxed one half of capital gains go into this account and are then available to be paid as a tax-free dividend out of the corporation. Why? Because this amount would not be subject to tax if the shareholder realized the gain personally. The other half of the capital gain is included in “aggregate investment income” as a “taxable capital gain” (as we have already seen). 26. Read subsection 89(1) and the definition of “capital dividend account”. The account includes the following items: (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) the tax free one half of capital gains (less the one half of capital losses), “capital dividends” (below) received from other companies, the tax-free portion of gains from eligible capital property, life insurance proceeds, and the tax-free portion of capital gains flowed through trusts (such as mutual funds). 27. An election must be filed with CRA (Canada Revenue Agency) to pay a tax-free “capital dividend”. Read subsection 83(2). The election must be filed before the dividend is paid. There is an ability to file late (read subsection 83(3)) on payment of a penalty. The company need only be a private company (Chapter 2) to pay a capital dividend. 28. If you elect too high, i.e., the dividend is greater than CDA, a penalty tax of 60%3 of the excess applies (read subsection 184(2), called Part III tax). One can elect, if all shareholders agree, to treat the excess as a taxable dividend within 90 days of a Part III assessment (read subsections 184(3) & (4)). 3 enhanced dividend tax credit when the GRIP dividend is ultimately paid as an eligible dividend to the individual shareholders. In accordance with proposed legislation to be effective in respect of capital dividends paid after 1999. The legislation is expected to be passed in due course. Page 129 Tax II Chapter 4 Spring 2013 Notes 29. Read the anti-avoidance rules for the CDA and the RDTOH contained in subsection 83(2.1) and subsection 129(1.2). The test is “one of the main purposes”. Read the decision in Canwest Capital Inc., a copy of which is enclosed with these materials. Page 130