Assessment Report 2002-03 - PTRC Peer Tutoring Resource Centre

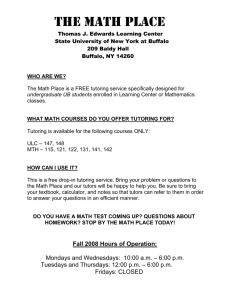

advertisement

Hong Kong University Grants Committee Teaching Development Grants ‘The Integration of Peer Tutoring Schemes into Academic Programmes/Subjects to Enhance Learning and Teaching in Universities in Hong Kong’ Report by External Adviser, Russell Elsegood, Murdoch University Director, STAR Peer Tutoring Programme July, 2003 Project Involvement: The external adviser’s role will cover the duration of the project (September 2002 to August 2004. This may be amended to mid-2005 subject to an approved extension to compensate for the unfortunate, enforced suspension during the SARS outbreak). In early October 2002 a series of presentations was made at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University for university staff involved in the sub-projects. The presentations were designed to provide a background to the history, growth, principles and practise of peer tutoring, and offered a variety of models for consideration. Each session emphasised several key fundamentals, as well as the practical procedures, and these points were reinforced in personal interviews with the proponent(s) of each sub-project. The fundamentals are: that before introducing peer tutoring there has to be a clear objective (or objectives) agreed and understood by the proponents – and those they recruit as peer tutors; benefits need to accrue to both the tutors and the tutees; the commitment needed for success has to be understood and agreed by all involved: the proponents/co-ordinators, the peer tutors, faculty, sponsors etc.; sustainability must be a priority and, to ensure credibility, evaluation must be a built-in component, not an after-thought. In the following months sub-project proponents have submitted draft project proposals which have been commented on, in detail, using a pro-forma comment document developed by the Project Leader Dr Patrick Lai and the sub-project teams. This method of sub-project ‘assessment’ has allowed for general comment and specific advice on various key issues that, in the view of the adviser, needed addressing. Peer tutor training, communication and reporting lines (between peer tutors and co-ordinators) and clearly defined strategies for evaluating and sustaining the projects have been the key issues that have needed inclusion, clarification or expansion. Proponents have re-submitted their sub-projects -- with necessary amendments and/or additions. In some cases more than one re-draft was necessary before the external adviser was satisfied and Dr Lai could be formally advised that the first phase of the sub-project was ready to proceed. 1 However, there is concern about the ability to achieve the ambitious objectives set for those sub-projects that do not have clearly-defined strategies for long-term sustainability. The adviser has remained available for consultation by e-mail during the period the draft proposals were under consideration – and since -- and several subproject co-ordinators have taken the opportunity to seek supplementary advice before re-drafting. Due to several factors – timetabling of courses and SARS being the main factors – it has not been possible for all eleven sub-projects to start or, at least, to achieve the milestones set in the approved proposals. However, written progress reports and video interviews with the sub-project co-ordinators (provided on CD-ROMs) , student tutors and tutees have been provided. 1. Overview The project is distinguished by (a) the large number of sub-projects to be introduced over the study period; (b) the ambitious objectives (refer previous comment); (c) the wide range of academic fields involved; (d) the equally-wide range of peer tutoring models employed. 1.1. Having reviewed the progress reports and interviews it is clear that some coordinators still perceive the peer tutors as de facto ‘teachers’ of subject content – supporting over-stretched staff, especially in courses with large classes. 1.2 Expectations and responsibilities of peer tutors (the majority of whom are paid) are much higher than in peer tutoring models this adviser is familiar with – to the point that some peer tutors are required to arrange bookings for the scarce rooms available for tutoring sessions. 1.3 That said, it also is apparent that most of the co-ordinators – ie those who have so far been able to launch their projects -- believe students recruited as peer tutors are properly trained and able to offer student tutees ‘learning support’. 1.4 For their part, peer tutors and tutees, generally, see advantages in being involved. However, in cases where co-ordinators have identified peer tutors who lack necessary skills, or need to improve their performance, it is imperative that remedial action be implemented promptly, through extra (or revised) training, to ensure that the peer tutors can feel confident in retaining credibility with their tutees. This is why good lines of communication and regular meetings between co-ordinators and peer tutors are strongly advocated. 1.5 There are varying degrees of supervision provided by the co-ordinators and, in some cases, this is neither regular nor always face-to-face. Peer tutors need to have easy access to a co-ordinator who will deal promptly with problems – whether they are tutees’ issues or the peer tutors’ motivation. 2 1.6 Reported cases of poor attendance by tutees needs to be addressed before peer tutors’ commitment and enthusiasm are undermined, making it more difficult to recruit peer tutors in the future. 1.7 Better matching of tutees’ needs (academic as well as time) to peer tutors’ skills and availability should be considered as a matter of priority. Matching and timetabling are known to be potential hazards to sustaining effective peer tutor/tutee relationships – a point made during the initial workshops/interviews for sub-project co-ordinators. 1.8 The October workshops and interviews also emphasised that regular communication for two-way feedback is an essential part of the support co-ordinators must establish with their peer tutors. 1.9 Appointment of a part-time co-ordinator is RECOMMENDED in cases where it is difficult – if not impossible -- for senior academic staff, even with the best will and intentions, to • handle the day-to-day issues in a full-fledged peer tutoring programme (recruitment, training, matching, monitoring); • maintain the necessary, on-going co-operation of subject co-ordinators; • liaise with Deans and departmental/faculty heads etc. 1.10 The expectation that university students will acquire and demonstrate ‘all round’ skills (eg in leadership, teamwork, communication etc.) needs to be more widely and actively promoted to staff and students if the role of peer tutoring is to be fully understood and integrated in the university. And it is so RECOMMENDED 2.Sub-project Progress 2.1 Of the eleven sub-project progress reports received, four were cases where active peer tutoring is yet to begin – ie in September 2003. 2.2. Two of those cases – in The Hong Kong Polytechnic University’s School of Nursing – nevertheless raise some interesting issues. 2.3 Dr Margaret O’Donoghue has specifically drawn attention to ‘disappointing’ assessment results among students taking the Clinical Microbiology course in Year II Higher Diploma Nursing. 2.4 It will be interesting to see whether the small Group peer tutoring by honours students can be an effective ‘early-intervention’ mechanism. 2.5 It will require close monitoring by the sub-project coordinator/course supervisor and, above all, support for peer tutors who identify students potentially ‘at risk’. 3 2.6 Implementing further action to support ‘at risk’ students will, of course, remain the responsibility of the course supervisor but may benefit from enlisting input from the relevant peer tutor(s). 2.7 In the case of the sub-project led by Mrs Maureen Boost, the proposal mentioned that peer tutoring had been earlier introduced in two subjects: Medical microbiology and Cellular pathology. 2.8 Though well received by students in the former, students in Cellular pathology ‘were not as pleased….(which, it is said) can be attributed to the different approach of the subject leader in this case.’ 2.9 This highlights the need to have all potential participants fully briefed before introducing peer tutoring, and it is evident the sub-project leader is already mindful of this by proposing the development of a peer tutoring manual. This is COMMENDED to all sub-project co-ordinators 2.10 While the present project focusses exclusively on students in Medical microbiology, is it possible that the best practice developed in this case may be tried, again, in Cellular pathology? 3.1 The sub-project in nursing at Hong Kong University provides a good example of pre-launch consultation. Dr Agnes Tiwari briefed staff and student ‘on the purpose, design and implementation of the peer tutoring scheme.’ 3.2 The briefings were supplemented by workshops for the peer tutors on their roles and responsibilities, and the development of tutoring and conflict-management skills. 3.3 Pre and post-intervention focus group interviews were held with peer tutors, tutees and a control group. A RECOMMENDED process for projects that follow this model. 3.4 Tutors and tutees reported that their involvement in the project motivated them to learn, but it is not evident from the progress report whether the peer tutoring had any influence on other, specific issues raised in the interviews and cited in the subproject’s objectives ie ‘…..understanding of (the) professional roles in nursing and demands made on them as professional nurses’. 3.5 How their responses compare with the focus group is not mentioned and this will need to be addressed in the next reporting period. 3.6 It would also be useful to learn whether/how it is planned to extrapolate this small-scale, one-to-one project into a wider programme. RECOMMENDED that a medium/long-term strategy be developed in the next reporting period. 4.1 The sub-project proposal appended to the report from Professor Agnes Gardner requires fine tuning before going into its final state. Suggestions made by the 4 advisers are being considered by Professor Gardner at the time of report writing and it is anticipated that a final proposal will come up before the second phase of the project. 4.2 Although peer tutoring for first-years studying Human anatomy in the Department of Rehabilitation sciences is yet to start, Professor Gardner has spent the intervening time substantially revising her proposal. 4.3 The objectives of the sub-project are ambitious and, although well supported by the rationale, seem difficult to achieve unless there is a well-defined strategy to sustain the sub-project beyond its current 10-sessions. (Refer RECOMMENDATION in 3.6) This applies particularly in verifying examination/assessment performance of peer tutored and non-tutored groups of students. While anecdotal evidence suggests improvements of this nature can be effected through sustained peer support, there have been conflicting results in the very few, longitudinal studies of this nature reported in the literature. (For further information, Keith Topping’s research on evaluation – cited in the list of references provided to all sub-project co-ordinators – is commended.) 5.1 Introducing peer tutoring as a compulsory component of the BSc (Honours) Radiography programme is unique among the sub-projects. 5.2 It would be valuable to learn what proportion of students ‘…did not want to take on the role (of peer tutor’ and opted, instead, to undertake extra assignment work. RECOMMENDED that this be addressed in the next reporting period. 5.3 Interestingly, in light of experiences in established programmes elsewhere, peer tutors’ responses in the evaluation questionnaire reflected less enthusiasm about the benefits of peer tutoring than the tutees; though the project leader, Dr Jan McKay, notes that the tutors’ views in interviews and comments in their reflective diaries suggest a positive impact. 5.4 The compulsory nature of this project and, possibly, a lack of awareness among students of the need to develop wider, generic skills (eg leadership -- Refer RECOMMENDTION in 1.10) before graduating may be contributing factors influencing the peer tutors’ documented views. 5.5 What was particularly noticeable from the pre and post-implementation data was that the peer tutors rated the experience as of low value in improving interpersonal skills. In studies elsewhere peer tutors have consistently rated this as one of the most valuable outcomes of the experience. RECOMMENDED that the variation reported in this case be further investigated in the next phase of the project. 5.6 As noted with other sub-projects, scheduling peer tutoring sessions presents a challenge, even when the peer tutors are well supported – as in this case with a project assistant. 5.7 Consistency in time and venue for meetings is important in building credibility for peer tutoring programmes and Dr McKay is already well aware of this and has signalled the need for improvement in the next reporting period. 5 5.8 It is RECOMMENDED that the foreshadowed ‘cascade’ system of peer tutoring (since deferred) only be pursued on a students’ needs basis and as part of a medium to long-term sustainability strategy. 6.1 The 1997/98 peer tutoring experiment in the Institute of Textiles and Clothing was halted due to lack of funding. As Dr Ng’s progress report on the current subproject shows equally-favourable signs of peer tutoring’s potential it is RECOMMENDED that in the next reporting period a medium to long-term sustainability strategy be prepared to ensure that the advantages of this latest initiative are not lost. 6.2 The 1:3 and even 1:1 ratio of peer tutors to tutors is commendable, but is it sustainable? 6.3 The responses to questionnaires suggest that tutees have gained substantially more from the peer tutoring than the tutors. Though the tutors regard the experience as enjoyable and would recommend it to others, little more than 40% of them believe it has improved their competence (presumably in the course requirements) or communication skills. 6.4 It is early days for the project, but these outcomes – in relation to the specific aims and objectives set for peer tutors in the Sub-Project Proposal (#1 a-d) – need closer scrutiny. Regular, informal feedback in communication between peer tutors and the co-ordinator will be useful in fine-tuning procedures to keep the attainment of these objectives on track. While it is important that peer tutors enjoy the experience of helping others, it is equally important, in the interests of sustaining a programme, that the peer tutors should gain new or enhanced skills. It is RECOMMENDED that the issue of improving, evaluating (and acknowledging) peer tutors’ acquisition of skills, as set out in the sub-project’s aims and objectives, be a strategic priority in the next reporting period. (NOTE: Some peer tutors in the STAR Programme have reported improved academic performance in their own courses which they attribute to their experience in peer tutoring others.) 6.5 Further evidence that the benefits for tutees -- as set out in the sub-project proposal (#2 a-c) – have been addressed and evaluated will be sought in the next reporting period. In particular, what success there has been in instilling/improving teamwork. 7.1 There is insufficient detail in Dr Wong’s progress report to make any meaningful or useful comment, but I shall be keenly interested – in the next reporting period – to see whether the introduction of peer tutors has had any evaluated effect on assisting transition for freshmen and, specifically, whether the addition of peer tutoring to the remedial support for students ‘…from the Mathematics track…..(has helped them) to catch up with the human science subjects’. 8.1 Although not mentioned in his written progress report, tutee absenteeism is a specific concern mentioned by sub-project co-ordinator Mr Yip. However, 6 examination of this issue, possible reasons and remedial action are not included in the targets for the next reporting period. RECOMMENDED that this be added to the issues to be addressed. 8.2 Given the key aims/objectives for this sub-project, the initial analysis of pre and post-questionnaires does not indicate what, if any, effect the introduction of peer tutors has had on assisting transition. RECOMMENDED that this be addressed in the next reporting period. 8.3 As with most, if not all the sub-projects greater attention needs to be given to matching peer tutors with tutees. In this case it is evident, from the outset, that tutees have preferences in who tutors them ie they ‘…dislike the peer tutor to be a student in their own class or have the same gender as them.’ RECOMMENDED that the question of ‘matching’ peer tutors and tutees be surveyed across the sub-projects and that it be a subject for discussion at a pre-semester seminar for co-ordinators. 9.1 The experience of tutees’ preference in peer tutors referred to above immediately poses questions in relation to the co-peer tutoring model adopted by Dr Jinlian Hu. Positive outcomes are reported, but there are no data provided to support these findings, though the original proposal suggested -- #1 (b) – ‘formal evaluation, that might for example include: • pre- and post-questionnaire surveys • focus group interview with students • ‘measurement’ of actual student learning outcomes • assessing any changes in students’ attitudes (to teaching/learning, leadership etc.) RECOMMENDED that more details of evaluation methods and outcomes be provided in the next reporting period 9.2 More details, please, on the reasons for the decision to ‘Separate the tutors and tutees in the class….’ 9.3 Since ‘more training for tutors’ is advocated it will be helpful to know what specific concerns/shortcoming (in tutors’ preparation) need to be targetted. 9.4 RECOMMENDED that a peer tutoring manual specific to the needs of the Textile Department be prepared to address the issues identified by the co-ordinator in Item 1.3 of the progress report. 9.5 It was originally intended to carry out this sub-project with 40 Final Year students in ‘Hi-TechTextiles’, but the progress report refers to just ‘three groups of three students each’. The variation in the numbers of students to be involved is not explained in the progress report. More information please. 10.1 The BUSS Department has had prior experience with peer tutoring, but given that this department is ‘disappearing in the restructuring of the Faculty’ the future for peer tutoring requires a strategic, long-term sustainability plan and this is COMMENDED to the new Faculty Teaching and Learning Committee. 7 10.2 The more ‘objective’ evidence of tutees’ ‘before and after’ grades added to the tutees’ evaluation of the ‘value’ of peer tutoring may add valuable weight to the subjective evidence that has sustained peer tutoring in BUSS over previous years. [Though attention is drawn to the cautionary note in #4.3 above viz: ‘ While anecdotal evidence suggests improvements of this nature (ie tutees’ academic performance) can be effected through sustained peer support, there have been conflicting results in the very few, longitudinal studies of this nature reported in the literature.’] It is, nevertheless, RECOMMENDED that collation and analysis of this additional evidence be budgetted for the next reporting period. 10.3 While acknowledging that ‘The number of Tutors and Tutees will be driven by supply and demand, as in the past’, BUSS’s past experience also suggests that peer tutoring has been worthwhile, which prompts the question of whether more active efforts should be made to promote its values – to tutors and tutees -- particularly if the University moves to requiring more opportunities for (and evidence of) students’ ability to gain and demonstrate generic/workplace skills before graduation. RECOMMENDED that the new Faculty Teaching and Learning Committee consider the integration of peer tutoring in strategies aligned with the University’s expectations for students to develop and demonstrate these ‘extra-curricular’ skills. 11.1 The selection process for peer tutors and the ‘quality assurance’ through ‘close monitoring of peer tutors and tutees’ are commendable aspects of the sub-project coordinated by Mrs Ann Cheung. However, timetabling of peer tutoring is already highlighted as an issue, with tutees wanting earlier access to peer tutors. Experience has shown that early recruitment of peer tutors and matching to peer tutees is a factor in the success and sustainability of programmes. It is RECOMMENDED that strategies be established to facilitate early recruitment of peer tutors, and that promotion of the benefits for tutors and tutees be incorporated in planning for the next reporting period. Evaluation As part of the evaluation process, videoed interviews have been conducted with peer tutors and tutees. 12.1 As a general observation it appears that, despite several concerns expressed by both groups (tutors and tutees), the concept of peer support has promising potential in offering benefits to the participants – and the teaching staff as well. 12.2 From the tutors’ perspective the main concerns were poor attendance by tutees; the tutees’ lack of preparation and preparedness to participate in group discussions and the excessive expectations/demands of tutors (ie some tutees expecting tutors to provide the answers). More than one group of tutors cited the fact that their assigned tutees did not take the sessions seriously enough. Problems in arranging meetings with tutees and, paradoxically, running out of time at sessions were also mentioned. 12.3 Several tutors felt they lacked sufficient guidelines on their roles and what was expected (by the course lecturer) to be covered in a session. 8 12.4 Both tutors and tutees constantly referred to peer tutoring as ‘teaching’ and this is not the widely-accepted role of peer tutors. Peer tutors are not equipped as teachers, so their concurrent roles – as facilitators and mentors -- need to be made abundantly clear to both those recruited as tutors, and those first-year students who choose (or are chosen) to participate. 12.5 For their part, tutees also expressed concerns about lack of contribution to group discussions; lack of preparation by tutors (hence a perception that the information they were being given was not correct), and some felt there was not enough time allocated for sessions – or not enough sessions – to cover the subject material. 12.6 While these may be seen as negatives, they are not uncommon at the start of peer tutoring programmes and are, generally, overcome if early corrective measures are instituted. 12.7 Attention to adequate training of peer tutors and clear (written) guidelines on the duties, expectations and responsibilities of all participants (tutors, tutees and course lecturers) will be the major factors in addressing the issues mentioned above. 12.8 Several sub-project leaders have suggested producing a manual for tutors and course lecturers/co-ordinators and this is strongly recommended. 12.9 All prospective tutees must have an introductory briefing from the sub-project leader/course lecturer on the roles and responsibilities of peer tutors and the guidelines they (the tutors) will work within. 12.10 Overall, the interviews provide strong evidence that tutors and tutees experienced benefits from their participation. 12.11 The most commonly expressed ‘positives’ from the peer tutors were that • they, personally, gained skills in communication, working with a team (groups) and time management, which were acknowledged as useful for their future work and careers; • they gained a sense of contributing to their younger peers’ (the tutees) knowledge and/or practical experience; • new friendships were established, and • they gained a greater understanding of their own knowledge of the subject matter through having to revise material in preparation for assisting their tutees. 12.12 It was particularly interesting (and pleasing) to see how often peer tutors said they consulted with or shared experiences with other peer tutors in the same discipline. This is to be encouraged. 9 12.13 Tutees were, overall, equally positive about the help they received in an atmosphere where they felt less inhibited about asking questions and seeking advice or help. 12.14 The most common references were to having someone • openly willing to share experiences and knowledge; • who was a good listener – and willing to listen; • a friend as well as an academic support person (usually described as a teacher; though this conflicts with the fairly common – and probably unfair -- criticism that tutors were perceived as not well-prepared to teach); • who, through the (extra) peer tutoring sessions, gave them a deeper understanding of the subject material. 12.15 Whether the peer tutoring support translates to better academic performance is still open to question – particularly after such a short experience – but there are signs that many first year students felt that their transition to university study had been made easier by the friendly support and advice offered by more senior students. Summary 13.1 While the majority of sub-projects have made a promising start with peer tutoring (despite the difficulties created by the SARS outbreak) several key issues – all of which were raised during the initial workshops/interviews in October -- have been identified in this report and need to be addressed, as a matter of urgency, before beginning the second phase. 13.2 It is RECOMMENDED that a seminar for sub-project leaders be convened in early November to discuss the issues raised and to share feedback from their experience so far. 13.3 As mentioned above, this project is distinguished by the large number of subprojects to be introduced over the study period; the ambitious objectives; the wide range of academic fields involved, and the equally-wide range of peer tutoring models employed. 13.4 It is a major challenge for peer tutoring to be planned and introduced on such a scale as this. Successful experience elsewhere suggests that it should be introduced incrementally; usually through a single, small pilot project setting modest objectives and testing policies and procedures over a minimum of a year. While there is evidence that some participants in the sub-projects have had experience with peer tutoring (albeit on a small, somewhat ad hoc basis), for most this is a new venture and hence one that requires a clear understanding of the fundamental required for long-term success ie the commitment and communication required from and between all participants – co-ordinators and peer tutors -- short and long-term objectives, and strategies for sustaining the sub-projects. 10 13.5 The advantage of a single pilot project is that procedures, such as selection and training of peer tutors, co-ordination and communication (between sub-project leaders and peer tutors and between peer tutors and tutees) can be thoroughly tested before being implemented on a wider scale. 13.6 Nevertheless, having embarked on eleven sub-projects, in a wide range of academic fields and with a range of peer tutoring models (paid/voluntary/compulsory; older students assisting new students; students from within the one class alternating role of tutor and tutee) there is the advantage of being able to compare and contrast the success of several, different approaches. Project and sub-project participants will benefit from formal and informal opportunities to exchange observations and experiences. 13.7 But, surveys and interviews with peer tutors and tutees have revealed that more attention needs to be given to some of the fundamentals cited above. 13.8 The co-ordinated, uniform training procedure for peer tutors that has been instituted is commended, but it is evident from the early evaluations that more detailed briefing on the roles and responsibilities of lecturers, sub-project co-ordinators and peer tutors is needed – with emphasis on improving communication. Indeed, improved communication (fostering two-way feedback – between co-ordinators, subject lecturers and peer tutors and peer tutors and tutees) is, perhaps, the single most important issue to be addressed in these early stages of the sub-projects. This is not uncommon in peer tutoring programmes and will continue to require monitoring and fine-tuning as experience dictates. 13.9 Given the project’s defined time-frame (and funding) it was advisable to establish modest sub-project objectives – at least short-term ones. 13.10 Observing and reflecting on how the concept of peer tutoring is implemented and received by students (ie peer tutors and tutees) and teaching staff might have been a sufficient objective for the first phase of the sub-projects. 13.11 Peer tutoring is not a short-term solution – whether that is improving academic performance or professional awareness of first-year students, or offering effective support to academic teaching staff. Given the relatively short time-frame of this project – and in the absence of long-term sustainability strategies -- one should be cautious about having too high an expectation of its outcomes. So, while having some reservations about the degree of adherance to and implementation of peer tutoring fundamentals, it is acknowledged that the scale of this project, the diversity of academic disciplines involved and the wide range of models being implemented is significant in the context of the evolution of peer tutoring. 13.12 As mentioned previously, peer tutoring projects, traditionally, grow from relatively small, pilot projects – invariably with an initial, limited objective (or objectives) eg focussing on a single subject with a history of high failure rates or, perhaps more broadly, trying to encourage greater student interest in a particular discipline such as science. 11 13.13 The scope of the Hong Kong project will, therefore, have particular interest and relevance for the international community of scholars and practitioners interested in peer tutoring. 13.14 What has been achieved so far through energy and determination, given the unfortunate (and unforeseeable) delays caused by the SARS outbreak, has been quite remarkable and augurs well for the project’s success. Adviser’s Background: Russell Elsegood is founder and Director of the Science/Technology Awareness Raising (STAR) Peer Tutoring Programme at Murdoch University in Western Australia. In 1989 he was co-founder of the WA Science Summer School, which first used university students as resident peer tutors in 1991. In 1993 he was awarded a British Council Travelling Fellowship to study peer tutoring in the UK – specifically the model pioneered at Imperial College, London. The STAR Programme was launched in 1994 and now has more than 100 university student volunteers (from Murdoch University and other WA universities) involved in regular, weekly peer tutoring. The STAR model has since been introduced in several Australian universities (eg RMIT, La Trobe, Monash and the University of South Australia), in New Zealand and Malaysia. Mr Elsegood has been an invited keynote speaker at Peer Tutoring Conferences in London, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and South Africa. He has also presented peer-tutoring workshops in Australia and New Zealand. In 1999 he organised and hosted the Asia Pacific Peer Tutoring Conference in Perth. Mr Elsegood has written extensively on peer tutoring, and has been published in UK, US and Australian journals and books on the subject. In 2002 he accepted the invitation from Dr Patrick Lai to be External Adviser to the current University Grants Commission-funded project 12