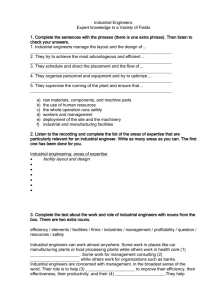

Increasingly, there are electric and computing engineers working “in

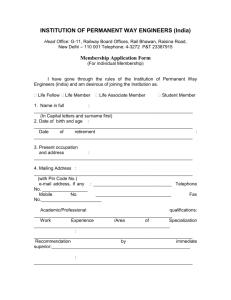

advertisement