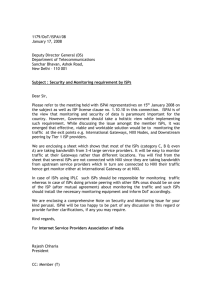

Liability of Internet Service Providers for Third Party Content

advertisement