Agenda Item 3-A - Control Deficiencies (Significant Comments)

advertisement

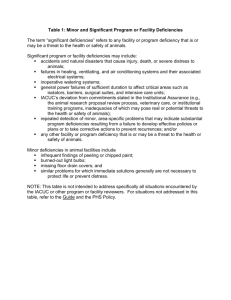

IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1703 Agenda Item 3-A Summary of Significant Comments and Task Force Recommendations— Exposure Draft of Proposed ISA 265, “Communicating Deficiencies in Internal Control” Introduction 1. The comment period for the exposure draft of the proposed ISA 265, “Communicating Deficiencies in Internal Control,” (ED-ISA 265) closed on April 30, 2008. A total of 48 comment letters have been received. A list of the respondents is included in the Appendix. 2. Overall, the majority of respondents were supportive of the proposed new standard. A few respondents, however, expressed strong reservations about the approach to the proposed definitions in ED-ISA 265. 3. The following section summarizes the significant comments received and the Task Force’s preliminary views and recommendations. Significant Comments A. Definitions of ‘Material Weakness’ and ‘Significant Deficiency’ 4. The approach proposed in ED-ISA 265 in relation to the definition (or non-definition) of the key terms ‘material weakness’ and ‘significant deficiency’, and the proposal to establish a new ISA, drew strong comments from a number of respondents. 5. Three respondents (ACCA, APB and IIA) questioned the need for an entirely new ISA on the grounds that the original purpose of the project was simply to clarify the meaning of the term ‘material weakness’. They felt that the proposed new ISA may cause confusion (for both auditors and management) by introducing new terminology, and could have a negative impact on smaller audits as well as result in additional costs. Accordingly, it was suggested that the IAASB study in more detail the impact of the proposed ISA on smaller audits, and retain the current requirements regarding communication of material weaknesses in ISA 260 (Revised and Redrafted), 1 ISA 315 (Redrafted) 2 and ISA 330 (Redrafted). 3 A respondent (EC) suggested that the IAASB postpone the adoption of the ISA until after the Clarity project and after the IAASB has given further thought to the goals it aims to achieve through a new standard. The EC noted that the consequences of replacing the concept of ‘material weakness’ with that of ‘significant deficiency’ are as yet unclear from an EU perspective. 6. Significant concerns were expressed by several respondents regarding the IAASB’s approach and rationale with respect to the definitions. They are as follows: 1 2 3 ISA 260 (Revised and Redrafted), “Communication with Those Charged with Governance.” ISA 315 (Redrafted), “Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and Its Environment.” ISA 330 (Redrafted), “The Auditor’s Responses to Assessed Risks.” Prepared by: Ken Siong (August 2008) Page 1 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1704 Some respondents 4 disagreed with the proposed withdrawal of the term ‘material weakness’. ACCA felt that although this term is not precisely defined in the ISAs, it is actually well understood, intuitive and long-established. It noted the lack of research evidence to support the IAASB’s view that inconsistency occurs to such extant that would raise public interest considerations. It suggested that the abolition of the term and its extant definition,5 coupled with the use of the proposed new term, would result in an overwhelming increase in the communication of trivial matters. BDO suggested that ED-ISA 265 seemed to take some but not all of the concepts from the PCAOB’s definition of ‘material weakness’ but fall short of its objective because it did not recognize that auditors’ responsibilities are focused on control issues that could cause a material weakness in the financial statements. A respondent (EC) commented that the ED did not clearly explain the relationship between significant deficiencies and material weaknesses, and therefore, EU companies and their auditors could be confused about their obligations under the EU Statutory Audit Directive as compared to the ISAs. The respondent noted that paragraph A8 of the ED6 appears to imply no difference between the two concepts, or alternatively two totally different concepts. It suggested that the ISA should at least clarify that the concept of a significant deficiency is broader than that of a material weakness (as defined or practiced in the US or the EU), and that the auditor should be required to include material weaknesses defined under domestic regulations or practiced in the markets when reporting significant deficiencies to those charged with governance. A few respondents 7 disagreed with the IAASB’s rationale that if two different definitions of the term ‘material weakness’ were to co-exist in IAASB and PCAOB standards, this could generate confusion, and lead to attempts at reconciling their meanings for various reporting purposes. The respondents noted that since the IAASB’s definition is directed at communication with those charged with governance, no “reconciliation” of the definitions would ever occur in practice. They felt, instead, that by allowing other regulators to define the term within the context of their environments greater confusion and inconsistency would be created as compared to adopting an IAASB definition which is different from that of the PCAOB. Another respondent (CNCC) further argued that the proposed ISA could cause confusion for auditors, regulators and the public because of the existence of different concepts (i.e. ‘material weakness’, ‘significant deficiency’, and ‘deficiency’) in the ISAs, the EU 4 ACCA, BDO, CNCC, EY and IDW. 5 Extant ISA 315, “Understanding the Entity and its Environment and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement,” defines ‘material weakness’ as one that could have a material effect on the financial statements. 6 Paragraph A9 of ED 265 states: “Law or regulation in some jurisdictions may establish requirements for the auditor to communicate to those charged with governance or to other relevant parties (such as regulators) details of specific types of deficiencies in internal control that the auditor has identified during the audit, and may define terms such as “material weakness” for this purpose.” 7 ACCA, EY and IDW. Agenda Item 3-A Page 2 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1705 Statutory Audit Directive, and local laws and regulations. Accordingly, these respondents suggested that it would be in the international public interest for the IAASB to take the lead and provide a definition that could be used globally, thus avoiding a proliferation of definitions in practice. (This view was also supported by some CAG Representatives at the September 2007 IAASB CAG meeting. Another CAG Representative supported a definition of material weakness that would be consistent with the PCAOB’s.) 7. A few respondents8 questioned the appropriateness of the proposed definition of a significant deficiency. EI and ICAEW commented that the definition seemed to be tautological and circular as the deficiencies to be communicated to those charged with governance would be those “that are of sufficient importance to merit the attention of those charged with governance.” IDW commented that by using the same term (i.e. ‘significant deficiency’) and adopting fundamentally the same definition as that used by the PCAOB, there would be a strong legal presumption in those jurisdictions which adopts ISA 265 that the IAASB definition has the same meaning as that of the PCAOB. It added that, resultantly, those jurisdictions adopting ISA 265 would effectively be adopting the PCAOB’s definition of material weakness since the PCAOB standard defines the relationship between a significant deficiency and a material weakness. IDW suggested that this would not be acceptable to many jurisdictions (including some in the EU) where the concept of material weakness is incorporated into local law or regulation. IDW further expressed the view that if the PCAOB definition of significant deficiency were to be applied in ISA 265, the threshold for reporting deficiencies to those charged with governance would be too low based upon IDW’s interpretation of the meaning of that definition, which would lead to the reporting of many deficiencies that are not of governance interest. Two of the respondents (CNCC and IDW) suggested that the IAASB should define the term ‘material weakness’ but that this definition should not be the same as the PCAOB’s. IDW was of the view that the PCAOB’s definition of material weakness is flawed on the grounds that this scopes in deficiencies with remote risks of not preventing, or detecting and correcting, material misstatements, which IDW believes sets too low a threshold. Accordingly, IDW suggested the following alternative definition of material weakness: “A deficiency in internal control relevant to the audit that does not reduce to an acceptably low level the risk that a material misstatement in the financial statements will not be prevented, or detected and corrected.” IDW also suggested the following alternative definition for the term ‘significant deficiency’: “A deficiency, in internal control relevant to the audit, that is of governance interest because the deficiency is a material weakness, or close to being a material weakness, or would become a material weakness when reasonable changes in circumstances occur.” 8 EI, ICAEW and IDW. Agenda Item 3-A Page 3 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1706 8. A respondent (EY) suggested that as the definitions of the terms ‘deficiency’ and ‘significant deficiency’ in the proposed ISA are closely aligned with those of the PCAOB standard, the definition of ‘material weakness’ in the ISA should also be closely aligned with that standard. The respondent argued that this would help avoid unnecessary differences in definitions internationally. 9. A respondent (Basel) appeared to have misunderstood the IAASB’s rationale for replacing the term ‘material weakness’ with ‘significant deficiency’. The respondent interpreted this change as meaning a strengthening of the ISA through lowering the threshold for identifying control deficiencies that should be communicated in writing to those charged with governance.9 Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 10. The Task Force noted that many of the above arguments were considered and debated by the IAASB when it finalized ED-ISA 265. During its deliberations, the IAASB consulted the EC on the possible approaches regarding whether or not to define the term ‘material weakness’, and the EC had indicated that it would not object to the ISA not using and defining that term if the project went ahead. 11. Clearly, however, there are a minority of respondents who strongly believe that the public interest would be better served by having a definition of material weakness in the ISA, even if that is different from the PCAOB’s definition. This view is also strongly supported by a member of the Task Force. Further, the EC seemed to have concluded that if the ISA were to use and define the concept of ‘significant deficiencies’, it should also treat material weaknesses (however defined under domestic regulations or used in practice) as a subset of those to be included when reporting significant deficiencies to those charged with governance. 12. The Task Force notes that the overriding objective of the ISA is communication as a byproduct of the audit. The majority of the Task Force is of the view that if the ISA were to address the categorization of material weaknesses within the broader subset of significant deficiencies, this could force a more rigorous evaluation process than was originally intended by the ISAs or should be required. The majority of the Task Force believes that this outcome would represent a significant extension of the auditor’s responsibilities under the existing standards, which the IAASB had agreed should not be the purpose of this project. Given the preponderance of respondents supporting the approach taken in the ED, the majority of the Task Force believes that this approach should be retained. 13. Nonetheless, the Task Force agreed that clarification could be provided in the guidance to recognize the fact that domestic law or regulation may impose additional requirements on the auditor (particularly for audits of listed entities) to evaluate the severity of significant deficiencies in order to identify a subset of those as material weaknesses for reporting purposes. Such law or regulation may define the relevant threshold for that purpose. 9 The IAASB had not intended to lower this threshold but merely to substitute the term ‘significant deficiency’ for “material weakness” in the ISAs. Agenda Item 3-A Page 4 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1707 Accordingly, the Task Force proposes to amend the guidance in paragraph A8 of the ED to that effect (see paragraph A9).10 14. Regarding the issue of whether a separate ISA is needed for the topic, the Task Force does not believe that arguments of a ‘fatal flaw’ nature have been raised by the few respondents who argued against a separate ISA. The Task Force believes that there is insufficient ground for the IAASB to reconsider this proposal. Accordingly, the Task Force recommends that the separate ISA approach be retained. Matters for IAASB Consideration Q. In the light of the responses, does the IAASB agree that: (a) The approach proposed in the ED remains appropriate and should be retained; and (b) Clarifying guidance should be provided to explain that law or regulation may impose additional requirements on the auditor to evaluate the severity of significant deficiencies in order to identify a separate class as material weaknesses? B. Scope of the ISA 15. Two respondents (APB and NZICA) asked why the objective in ED-ISA 265 was restricted to communications about internal control relevant to the audit, particularly given the indication in paragraph 3 of the ED that nothing in the ISA precludes the auditor from communicating control matters that are not relevant to the audit. One of them (NZICA) further suggested that the definition of ‘deficiency in internal control’ should be amended so as not to restrict it to matters that relate directly to possible misstatements in the financial statements. The respondents were of the view that the restriction in the objective implied that an auditor could decide not to communicate an identified significant deficiency if it was considered not relevant to the audit, which they felt would be inappropriate. Instead, they suggested that the ISA should require the communication of any non-trivial deficiencies, whether or not relevant to the audit. NZICA pointed out that ISA 260 (Revised and Redrafted) states that one of the objectives of communication is to “provide those charged with governance with timely observations arising from the audit that are significant and relevant … .” The two respondents noted that if the IAASB were concerned about the scope of the auditor’s responsibilities, it could add a statement in the introduction to the effect that nothing in the ISA requires the auditor to obtain an understanding of internal control that is not relevant to the audit. Accordingly, the respondents suggested that the phrase “relevant to the audit” should be deleted from the introduction to the ISA, the objective, the proposed definition of a significant deficiency, and other places in the ISA where it appears. 16. Two respondents (GT and NZICA) commented that there seemed to be an apparent inconsistency in ED-ISA 265 in that the definition of a ‘deficiency in internal control’ does not include the phrase ‘relevant to the audit’, which is used in the objective, in the 10 References to paragraphs in the ISA are to the revised draft unless otherwise stated. Agenda Item 3-A Page 5 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1708 definition of a significant deficiency, and in other parts of the ISA. They suggested that this may cause confusion in practice. One of them (GT) suggested addressing the issue by: Expanding the definition of a deficiency in internal control as follows: “…A control relevant to the audit that is either missing or… ;” and Eliminating the phrase ‘relevant to the audit’ within the objective and the definition of a significant deficiency. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 17. The Task Force disagree with the respondents that the objective in ED-ISA 265 is “restricted” to communications about internal control relevant to the audit. No limitation is in fact being placed on the auditor given that paragraph 3 of ED-ISA 265 states that “nothing in this ISA precludes the auditor from communicating control matters that the auditor has identified during the audit that are not relevant to the audit but that the auditor considers important.” Rather, what the proposed objective seeks to achieve is to place an obligation on the auditor to communicate identified deficiencies only when these are relevant to the audit. To require the auditor to communicate deficiencies in internal control that are not relevant to the audit under all circumstances would not be appropriate as it would result in a significant extension of the auditor’s responsibilities under the extant ISAs.11 In addition, the Task Force notes that the relevant communication objective in ISA 260 (Revised and Redrafted) deals with the narrower responsibility of those charged with governance to oversee the financial reporting process. Accordingly, the Task Force believes that no change should be made to the proposals in the ED in this regard. 18. The Task Force, however, believes that the perceived inconsistency in the use of the phrase ‘relevant to the audit’ in the definitions of a deficiency and a significant deficiency actually points to an incomplete definition of a deficiency in internal control in ED-ISA 265. This is because, while the proposed definition of a deficiency appropriately deals with the likelihood of misstatements in the financial statements (and therefore it concerns matters related to the financial reporting process), it does not address failures in controls that are not related to financial reporting but are nonetheless relevant to the audit (within the meaning of that term in ISA 315 (Redrafted)12). 19. The Task Force believes that there are two possible approaches to resolving this inconsistency: 11 The requirement under the extant ISAs is for the auditor to communicate material weaknesses in the context of financial reporting, as a material weakness is defined as one that could have a material effect on the financial statements. 12 Paragraph A58 of ISA 315 (Redrafted) states the following: “Controls over the completeness and accuracy of information produced by the entity may be relevant to the audit if the auditor intends to make use of the information in designing and performing further procedures. Controls relating to operations and compliance objectives may also be relevant to an audit if they relate to data the auditor evaluates or uses in applying audit procedures.” Paragraph 12 of ISA 315 (Redrafted) states that “most [but not all] controls relevant to the audit are likely to relate to financial reporting.” Agenda Item 3-A Page 6 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1709 (a) Define a deficiency by reference to internal control relevant to the audit but expand the definition to account for deficiencies in internal control that are not related to financial reporting. This would retain the current scope of ED-ISA 265 in that it would continue to address the communication of deficiencies in internal control relevant to the audit; or (b) Limit the definition of a deficiency to only controls that are related to financial reporting, i.e. leave the definition in ED-ISA 265 unchanged. 20. One could argue that the first option (and the approach that ED-ISA 265 effectively took through the requirement to communicate deficiencies in internal control relevant to the audit) in fact represents an extension of the auditor’s responsibility to communicate material weaknesses under the extant ISAs, given that material weaknesses are defined only in relation to material effects on the financial statements (i.e. the relevant controls in respect of which the auditor has a communication responsibility would seem to be those related to financial reporting only). 21. The second option would appear to represent the current requirement to communicate material weaknesses in the extant ISAs, even though ISA 315 (Redrafted) establishes a broader requirement for the auditor to obtain an understanding of internal control relevant to the audit. The Task Force believes that this option is the more appropriate one insofar as the auditor should have an obligation to report. If this were the principle to be adopted, it would not preclude the auditor from communicating deficiencies in internal control relevant to the audit but that are not related to financial reporting, just as the ED proposed to give the auditor flexibility in communicating control matters that are not relevant to the audit. 22. Accordingly, the Task Force proposes that the phrase ‘relevant to the audit’ be deleted from the objective (paragraph 5) and the definition of significant deficiency (paragraph 6(b)). The Task Force also proposes to clarify: a) In paragraphs 1 and 2 that the ISA deals only with internal control relating to financial reporting; and b) In paragraph 3 that nothing in the ISA precludes the auditor from communicating other internal control matters that the auditor has identified during the audit. Matter for IAASB Consideration Q. Does the IAASB agree with the Task Force’s view that that the auditor should only be required to communicate those deficiencies in internal control that are related to financial reporting, but that nonetheless the auditor may also communicate other internal control matters identified during the audit? C. Definition of the Term “Deficiency in Internal Control” Agenda Item 3-A Page 7 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1710 23. A few respondents13 commented that the proposed definition of a deficiency in internal control is not entirely consistent with ISA 315 (Redrafted). They noted that ISA 315 (Redrafted)14 explains that a specific control operating individually or in combination with other controls can effectively prevent, or detect and correct, material misstatements. In their view, a control failure can occur when a combination of controls fails to operate as intended. They therefore suggested that the definition of a deficiency in internal control be amended to reflect the possibility of controls not working effectively in combination, and therefore giving rise to an overall deficiency, even though they would be effective in isolation. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 24. The Task Force did not agree with the respondents that the definition should be amended. This is because broadening it to cover combinations of inter-dependent controls working together would introduce an element of significant complexity in the ISA. The Task Force believes that this suggestion would drive the auditor to always consider and investigate whether specified controls were intended to work with other controls, which would entail a significant expansion of work effort in evaluating whether deficiencies exist. Further, the Task Force noted that the term ‘control’ is defined very broadly in ISA 315 (Redrafted) to mean any aspect of one or more of the components of internal control. In addition, the Task Force noted that even if an individual control that is intended to operate in tandem with other controls were ineffective, it would still render the whole ineffective. 25. Accordingly, the Task Force recommends that no change be made in this respect. D. Use of the Term “Clearly Trivial” 26. Paragraph 1 of ED-ISA 265 stated the following: “This ISA does not address deficiencies in internal control the potential financial effects of which are clearly trivial.” ED-ISA 265 then included a cross-reference to paragraph A1 of [proposed] ISA 450 (Revised and Redrafted), 15 which explained the meaning of the term ‘clearly trivial’ in relation to misstatements. 27. 13 14 15 A respondent (PwC) disagreed with the use of the concept of ‘clearly trivial’ in ED-ISA 265. It commented that the term is always used in the ISAs in the context of misstatements. It noted that ‘clearly trivial’ is a quantitative threshold, and that using the same term in the context of deficiencies in internal control would be confusing because the determination of the significance of such deficiencies also involves qualitative considerations (i.e., both likelihood and potential magnitude). The respondent suggested that the phrase ‘other than CIPFA, ICAEW and ICAS. For example, ISA 315 (Redrafted), paragraphs A57 and A62. This paragraph is now paragraph A2 in the recently finalized ISA 450 (Revised and Redrafted), “Evaluation of Misstatements Identified during the Audit.” Agenda Item 3-A Page 8 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1711 of relatively minor significance’ be used to allow scope for more judgment and less emphasis on quantitative considerations. 28. Another respondent (ACCA) argued that the need to assess the potential financial effects of a deficiency may make it very difficult for the auditor to classify the deficiency as ‘clearly trivial’ because its financial effects are uncertain. In that regard, the respondent noted that [proposed] ISA 450 (Revised and Redrafted) stated that “when there is any uncertainty about whether one or more items are clearly trivial, the matter is considered not to be clearly trivial.” The respondent added that while any control over small cash balances could be considered to be clearly trivial, no control over a material transaction stream or asset or liability could be considered to be clearly trivial. The respondent was of the view that this would lead to minor deficiencies being communicated, which it felt would not be justifiable in cost-benefit or audit quality terms. 29. A third respondent (Basel) commented that although ‘clearly trivial’ deficiencies are scoped out in accordance with paragraph 1 of ED-ISA 265, paragraph 9 of the ED (regarding the requirement to communicate all deficiencies other than those that are clearly trivial) distinguished between deficiencies that are clearly trivial and those that are not. The respondent noted that this would create confusion as to whether the proposed ISA deals with three different categories of deficiencies. The respondent suggested that the proposed ISA should be clarified to either: Specify what the three categories are, i.e. significant deficiencies (to be communicated in writing to those charged with governance and to management); non-trivial, non-significant deficiencies (to be communicated in writing to management); and trivial (to be documented by the auditor but for which there would be no need to communicate); or Scope out clearly trivial deficiencies entirely, which would leave the proposed ISA limited to just the first two categories of deficiencies. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 30. The Task Force notes that the explanatory memorandum to ED-ISA 265 explained that the most important public interest consideration for the wide range of audits covered by the ISAs is to ensure that the auditor communicates identified non-trivial deficiencies in internal control to those parties within the entity who can competently deal with them on a timely basis. Accordingly, the IAASB’s original intention was to set the threshold for communication to management at the ‘non-trivial’ level. The overwhelming majority of respondents did not disagree with this proposal. (See also related discussion on Issue E below). 31. The Task Force, however, agreed with one of the respondents above that there could be potential for misinterpretation of the scope of the ISA if the term ‘clearly trivial’ were used as described in ISA 450 (Revised and Redrafted), given that the meaning of the term is linked to misstatements. Accordingly, the Task Force agreed that a different term should be used: ‘clearly inconsequential’ (see para 1 in the revised draft). This is terminology that is Agenda Item 3-A Page 9 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1712 already used in the ISAs Engagements.17 16 and in the International Framework for Assurance 32. The Task Force believes that using the phrase ‘of relatively minor significance’, as suggested by one of the respondents, could give rise to difficulties as it is unclear what the measure is relative to, and how the term ‘minor’ should be interpreted. 33. Finally, the Task Force recommends that the bracketed reference to deficiencies ‘other than those that are clearly trivial’ in paragraph 9 of ED-ISA 265 be deleted to eliminate the confusion regarding the categories of deficiencies addressed by the ISA. The scoping out of deficiencies that are clearly inconsequential in paragraph 1 of the ISA would make it unnecessary to further emphasize the point elsewhere in the ISA. E. Consistency Between Communication Requirement and the Objective 34. Several respondents 18 commented that the requirement to communicate identified deficiencies to management in paragraph 9 of ED-ISA 265 was inconsistent with the proposed objective. They noted that while the objective explicitly recognized the essential role of the auditor’s professional judgment in determining whether an identified deficiency is of sufficient importance to be communicated to management, paragraph 9 of the ED effectively removed the auditor’s ability to exercise that judgment by requiring the auditor to communicate all identified deficiencies to management (other than those that are clearly trivial). The respondents argued that the requirement would set the reporting threshold too low, resulting in, firstly, far too many deficiencies being identified and reported to management, and secondly, constraining the exercise of judgment. They added that management might not have an interest in all non-trivial deficiencies. A respondent also suggested that this could lead to an implicit requirement for the auditor to identify any missing control, even if not relevant to the audit. 35. Accordingly, the respondents felt that a more reasonable threshold would be desirable. A respondent (PwC) suggested that the threshold specified in the objective would be appropriate, i.e. those deficiencies that, in the auditor’s professional judgment, are of sufficient importance to merit management’s attention. Another respondent (IDW) suggested, in the context of its proposal for a different definition of the terms ‘material weakness’ and ‘significant deficiency’ (see Issue A above), that management would be interested in “those deficiencies that are significant deficiencies, close to being significant deficiencies or that would become such significant deficiencies when reasonable changes in circumstances occur.” This respondent justified its proposal on the basis that management may need to take action to mitigate those deficiencies that are material weaknesses, prevent other significant deficiencies from becoming material weaknesses, and prevent the other deficiencies from becoming significant deficiencies. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 16 17 18 For example, ISA 250 (Redrafted), paragraph 22. International Framework for Assurance Engagements, paragraph 48. BDO, EC, FEE, DnR, ICAS, IDW, IRE and PwC. Agenda Item 3-A Page 10 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1713 36. Given the strong concerns raised by the respondents, the Task Force believes that there is a need to reconsider the threshold for communicating identified deficiencies to management. As noted in the discussion of Issue D above, the original intent behind the requirement in paragraph 9 of ED-ISA 265 was for the auditor to communicate to management all nontrivial deficiencies that the auditor has identified during the audit to enable management to take appropriate action on them, on the grounds that this would serve the public interest. However, after further reflection in the light of the comments, the Task Force agreed that a requirement to communicate all identified deficiencies to management could be unduly burdensome and impractical. The Task Force agreed with the respondents that the auditor should have the flexibility to exercise judgment to determine which deficiencies are of sufficient importance to merit being brought to management’s attention.19 37. With regard to significant deficiencies, however, the Task Force believes that these should be automatically communicated to management as part of the requirement to communicate them to those charged with governance (See paragraph 9). (See issue H for a further discussion of the re-ordering of paragraphs 9 and 10 of ED-ISA 265). 38. Accordingly, the Task Force proposes that paragraph 9 of ED-ISA 265 be amended so that, rather than requiring the communication of all deficiencies identified during the audit to management, it should require the communication of deficiencies that the auditor judges to be of sufficient importance to merit management’s attention (see paragraph 11). F. Unconditional Requirement to Communicate 39. Paragraphs A10 and A11 in ED-ISA 265 made two statements that effectively render the requirement to communicate identified deficiencies to management unconditional: 40. 20 “… the fact that the auditor communicated a deficiency to management in a previous audit, or that management already had knowledge of the deficiency through other means (such as from relevant work done by internal auditors), does not eliminate the need for the auditor to repeat the communication if remedial action has not yet been taken.” Para A11: “… the requirement for the auditor to communicate deficiencies to management applies regardless of cost or other considerations that management may consider relevant in determining whether to remedy such deficiencies.” Several respondents expressed concerns regarding this unconditional stance: 19 Para A10: Some of them 20 commented that for some entities, particularly SMEs, once management has considered a deficiency but decided not to remedy it, management may wish to continue relying on close personal supervision instead of instituting The effect of this is to create 4 categories of deficiencies instead of the original 3: significant deficiencies; other deficiencies that merit management’s attention; other deficiencies that do not merit management’s attention; and deficiencies that are clearly inconsequential. The Task Force did not believe that deficiencies that do not merit management’s attention will necessarily be deficiencies that are clearly inconsequential. APB, BTR, CNCC, DnR, EY and NZICA. Agenda Item 3-A Page 11 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1714 extensive controls that management may not consider cost-effective. These respondents argued that in these circumstances, reporting the same issues to management would represent extra cost for the auditor to no benefit. They also highlighted the risk that automatic re-communication of deficiencies would harm the auditor’s relationship with the client. The respondents suggested, however, that if there has been a change in management, or if new information were to come to the auditor’s attention (e.g. the discovery of material misstatements or significant loss to the entity as a result of a deficiency), then it might be appropriate to repeat the communication. A few respondents 21 took the view that the auditor should not be required to communicate matters that have already been brought to management’s attention through other means, such as from relevant work done by internal auditors. They argued that if the auditor knows that management has received and read an internal audit report identifying certain deficiencies, it would be unnecessary to require the auditor to re-communicate those deficiencies. They noted that this approach would be consistent with the focus in the objective on those deficiencies “that the auditor has identified during the audit.” They also commented that an unconditional requirement in this regard may entail unnecessary costs and potentially confuse those charged with governance. Two other respondents (GT and IRBA) commented that a requirement to recommunicate to management deficiencies that are not significant would be unnecessary and onerous. They suggested that the ISA should allow the auditor to exercise judgment in determining whether a re-communication is necessary. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 41. The Task Force notes that the IAASB’s rationale for proposing to require the auditor to communicate identified deficiencies regardless of cost or other considerations, or to recommunicate deficiencies that have not yet been remedied, was that it would be in the public interest for the auditor to make management aware of control matters that need, or continue to need, management’s attention. Further, there is the possibility that management would resort to justifying inaction on the grounds of cost even though it might be costbeneficial to remedy the identified deficiencies. 42. Given the force of the concerns expressed by the above respondents, however, the Task Force believes that a degree of flexibility would be warranted in relation to the communication or re-communication of deficiencies that are not significant, i.e. the auditor should be permitted to exercise judgment in the circumstances in deciding when to communicate or re-communicate such deficiencies. In particular, it should not be necessary for the auditor to repeat information about deficiencies that are not significant if such information has been included in previously issued written communications, whether made by the auditor, internal auditors, or others within the entity. 21 EC, GT and PwC. Agenda Item 3-A Page 12 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1715 43. For significant deficiencies, however, the Task Force is of the view that it would be in the public interest that the requirement to communicate or re-communicate be unconditional because of the importance of these matters. The Task Force also agreed with the respondents’ suggestion that deficiencies that should be communicated should be those that the auditor has identified during the audit and not those that management or those charged with governance became aware of through other means. 44. Accordingly, the Task Force recommends that: The requirement to communicate significant deficiencies should apply regardless of cost or other considerations that management and those charged with governance may consider relevant in determining the need for remedial action (see paragraph A14); With regard to deficiencies that are not significant and that the auditor had communicated to management in a prior period, guidance be provided to explain that the auditor need not repeat the communication in the current period if management has chosen not to remedy them for cost or other reasons, or if the information is already included in previously issued written communications to management (see paragraph A23); The guidance dealing with re-communication in ED 265 be amended to focus only on significant deficiencies (see paragraph A15); and The reference to deficiencies that management has become aware of through other means (such as from internal auditors’ work) be deleted from the guidance originally proposed in ED 265 (see paragraph A15). G. Compensating Controls 45. Subparagraph 9(a) of ED 265 proposed that the auditor be required to communicate all identified deficiencies in internal control to management unless the auditor has obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence about the operating effectiveness of other controls that would prevent, or detect and correct, misstatements arising from the identified deficiencies. 46. Several respondents22 interpreted this proposal as implying a requirement for the auditor to test the operating effectiveness of the compensating controls to support a determination as to whether a deficiency exists in every instance, even though the IAASB had made its intention clear in paragraph A3 of ED-ISA 265 23 that there is no such obligation. A few of these respondents (EY and GT) took the view that subparagraph 9(a) of ED-ISA 265 improperly implied that compensating controls can eliminate a deficiency from being communicated to management. They suggested that this subparagraph should be deleted on the grounds that communication of deficiencies in internal control is a by-product of the audit and, therefore, those charged with governance can best understand the context of the communication if they are informed of all deficiencies identified by the auditor during the audit, regardless of the operation of compensating controls. In this regard, they pointed out 22 23 ACCA, AICPA, CNCC, EC, EY, GT and NZICA. Paragraph A3 of ED-ISA 265 stated: “This ISA does not require the auditor to obtain audit evidence regarding the design and operating effectiveness of these other controls.” Agenda Item 3-A Page 13 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1716 that paragraph A3 of ED-ISA 265 already stated that the existence of compensating controls does not change the fact that the auditor has identified deficiencies in internal control. 47. A few other respondents (APB, Basel and CEBS) suggested the need for clarification to the wording of subparagraph 9(a) in relation to the guidance in paragraph A3 of ED-ISA 265. One of them (APB) suggested that the ISA make clear that the requirement in subparagraph 9(a) relates to situations where management is already aware of the deficiencies identified by the auditor and has made the auditor aware of other controls that mitigate those deficiencies. This respondent felt that if management is not aware of the deficiencies identified by the auditor, then the auditor should inform management of them even if the auditor identifies mitigating controls. 48. One respondent (ICAS) commented that although paragraph A12 of ED-ISA 265 states that unless the auditor obtains evidence about the other controls, the auditor does not have sufficient appropriate audit evidence to conclude that a control deficiency does not exist, the auditor would also not have sufficient evidence to conclude that a deficiency does exist (i.e. if the other controls operate effectively, then there should be no deficiency). The respondent therefore noted that there is a risk that the auditor would report deficiencies that do not in fact exist. The respondent suggested that this issue could be addressed by requiring the auditor to test the operating effectiveness of these other controls when management brings those to the auditor’s attention, although this would place an additional burden on the auditor. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 49. The Task Force believes that in the first instance a clarification is needed to paragraph A12 of ED-ISA 265 in relation to the statement that “unless the auditor has obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence about the operating effectiveness of other controls that would prevent, or detect and correct, misstatements arising from the identified deficiencies, the auditor does not have sufficient audit evidence to conclude that a deficiency in internal control does not exist.” As some of the respondents have alluded to, there is an inherent inconsistency between this statement and the statement in paragraph A3 of ED-ISA 265 that the existence of compensating controls does not change the fact that the auditor has identified deficiencies in internal control. The Task Force believes that instead of an effective compensating control affecting the determination of whether a deficiency exists, it should affect the determination of whether any misstatements in the financial statements could arise as a result of the deficiencies. This is because a deficiency that has been identified remains a deficiency regardless of whether other controls compensate for the failing of the underlying control, but these other controls may fully compensate for the deficiency by preventing, or detecting and correcting, any resulting misstatements. 50. The question that then arises is whether the auditor should communicate an identified deficiency to management and, where appropriate, those charged with governance, if other controls can compensate for the failed control. Two of the respondents above (EY and GT) suggested that identified deficiencies should be communicated regardless of compensating controls, while one other respondent (APB) suggested a variation to this, i.e. if Agenda Item 3-A Page 14 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1717 management is not aware of the identified deficiencies, the auditor should inform management of them even if the auditor identifies mitigating controls. 51. After further reflection in the light of the comments received, the Task Force concluded that the overriding principle should be that identified deficiencies should be communicated regardless of the existence and operation of compensating controls. This is because compensating controls do not eliminate the fact that the auditor has identified deficiencies, although they may mitigate the effects of those deficiencies. Consequently, the auditor should simply communicate these deficiencies to management and, where appropriate, those charged with governance on the basis that these would need their attention. 52. The Task Force as a whole believes that this is the appropriate level of responsibility to establish given that: The extant ISAs do not impose any obligation, whether stated or implied, on the auditor to consider or test compensating controls when considering material weaknesses; and The communication of identified deficiencies is a by-product of the audit that should not require evaluation hurdles to be cleared in relation to compensating controls, i.e. deficiencies that have come to the auditor’s attention during the audit should simply be brought to the attention of management and, where appropriate, those charged with governance for their consideration. (A member of the Task Force, however, felt that not requiring the auditor to test compensating controls when management has brought these to the auditor’s attention would not serve the profession well, as this may potentially damage the auditor’s working relationship with management.) 53. Accordingly, the Task Force recommends that the precondition in subparagraph 9(a) of ED-ISA 265, and consequently the associated guidance in paragraph A12 of ED-ISA 265 and the last two sentences of paragraph A3 of ED-ISA 265, be deleted. This would eliminate the apparent confusion felt by some respondents regarding whether there is a requirement to test the operating effectiveness of compensating controls before the auditor communicates identified deficiencies. It would also turn into a non-issue the point raised by one respondent above that the auditor would not have sufficient evidence to conclude that a deficiency does exist if the auditor has not tested the operating effectiveness of other controls. 54. Nevertheless, in relation to significant deficiencies, the Task Force agreed that where the auditor has been informed by management, or otherwise knows, of the existence of compensating controls, the auditor may acknowledge this fact in the written communication of significant deficiencies and indicate whether or not the auditor has tested the operating effectiveness of such compensating controls (see paragraph A20). Matters for IAASB Consideration Q. Does the IAASB agree with the Task Force’s proposed revised approach to compensating controls in the ISA, and the proposed amendments noted above? Agenda Item 3-A Page 15 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1718 Q. Does the IAASB agree with the guidance proposed in paragraph A20 of the revised draft? H. Communicating in Writing to Management 55. The explanatory memorandum to ED-ISA 265 noted that the IAASB did not propose that the auditor be required to communicate all identified deficiencies formally to management in writing as this could place an undue and excessive documentation burden on the auditor, particularly in smaller entity audits. The IAASB therefore determined that the communication to management need not be in writing. 56. A small minority of respondents (CEBS and CPAB) questioned whether communicating such deficiencies in writing to management would place an excessive burden on the auditor. The respondents were of the view that the auditor would normally document any such communication with management in the auditor’s working papers anyway. They argued that communication of such deficiencies to management (and significant deficiencies to management and those charged with governance) is an important subsidiary outcome of the audit. Thus, they added, having a written record for management and auditors of what has been communicated would not only be useful for both management and auditors, but would also add value from a public interest perspective. The respondents also suggested that the communication need not be “formal,” as implied in the explanatory memorandum, but could simply be a copy of the auditor’s own documentation. 57. Another respondent (NZICA) suggested that oral communication alone would not be sufficient and would not be in the best interest of the entity as management would have no record of the matters raised and would not appreciate that the auditor expects the deficiencies to be remedied. 58. A respondent (CEBS) suggested that the proposed ISA should clarify that significant deficiencies also need to be communicated, preferably in writing, to management unless those significant deficiencies involve management. Another respondent (PwC) suggested switching the order of paragraphs 9 and 10 in ED-ISA 265, so that the auditor would, in the first instance, be required to communicate all significant deficiencies identified to both management and those charged with governance, and then any other identified deficiencies to management. 59. Two respondents (HKICPA and NZICA) commented that the guidance in paragraph A10 in ED-ISA 265 seemed to suggest that the communication with management would have to be in writing,24 contrary to the explanations given in the explanatory memorandum. They suggested a need to clarify the guidance and asked for additional guidance on the form of the communication with management. 60. A respondent (ACCA) noted that the communication of deficiencies will take place at the time management responds by providing information on other controls. Accordingly, given that such communication would already have taken place, the respondent disagreed with the proposed requirement that the auditor communicate to management as identified 24 This is presumably because the guidance explained how deficiencies reported in a prior period might be recommunicated in summarized form in the current period. Agenda Item 3-A Page 16 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1719 deficiencies those suspected deficiencies that management asserts are compensated by other controls. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 61. The Task Force notes that the IAASB debated at length the issue of whether to require the auditor to communicate all identified deficiencies to management in writing. As noted in the explanatory memorandum, the IAASB took the view that imposing such a requirement would place an excessive and unreasonable documentation burden on the auditor, especially given that many of the matters identified for communication may not be significant. This view seems to have been supported by the vast majority of the respondents. Further, the Task Force notes that ISA 230 (Redrafted) 25 only requires the auditor to document discussions of significant matters with management. To the extent that the auditor judges certain identified deficiencies not to be significant matters (and the Task Force believes that not all identified deficiencies will necessarily be significant matters), there would be no requirement to document these deficiencies. 62. Accordingly, the Task Force believes that it remains appropriate not to impose a specific requirement that all identified deficiencies be communicated to management in writing. However, the Task Force agreed that it would be appropriate to include a reference to the overarching requirement in ISA 230 (Redrafted) in relation to the documentation of discussions of significant matters with management to draw the auditor’s attention to the need to consider whether identified deficiencies, even if not qualifying as significant deficiencies, would nonetheless be significant matters requiring documentation under ISA 230 (Redrafted). For identified deficiencies that are not considered significant matters, the Task Force agreed that guidance be provided to indicate that the auditor may nevertheless find it helpful to document the discussions of such matters with management (see paragraph A22). 63. With regard to the communication principles in paragraphs 9 and 10 of ED-ISA 265, the Task Force agreed that these would be clearer if the ISA were to first require the auditor to communicate significant deficiencies in writing to both management and those charged with governance, and then any other identified deficiencies to management, with no requirement that the latter be communicated in writing. (See paragraphs 9 and 11 in the revised draft). The Task Force believes that this restructuring clarifies the original intent of the IAASB and responds to the concerns expressed by some of the above respondents. 64. With regard to comments from two of the respondents above that the guidance in paragraph A10 in ED-ISA 265 seemed to suggest that the communication with management would have to be in writing, the Task Force believes that this concern will have been addressed through a revision of this guidance to limit its context to significant deficiencies only, as further discussed under Issue F above. The Task Force did not believe that specific guidance would be necessary regarding the form of the auditor’s communication with management, given that such communication may be made orally. 25 ISA 230 (Redrafted), “Audit Documentation.” Agenda Item 3-A Page 17 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1720 65. Finally, the Task Force agreed that where the auditor has discussed the facts and circumstances of the auditor’s findings with management to confirm the existence of identified deficiencies, the auditor may consider an oral communication of these deficiencies to have been made to management at the time of the discussions. Therefore, in such circumstances, the auditor would not need to repeat the communication subsequently. (See paragraph A22). Matters for IAASB Consideration Q. Does the IAASB agree that there should not be a requirement that the auditor communicate identified deficiencies to management in writing? Q. Does the IAASB agree that it would be appropriate to include a reference to ISA 230 (Redrafted) in the guidance in relation to the overarching requirement to document discussions of significant matters with management? Q. Does the TF agree that paragraphs 9 and 11 as restructured in the revised draft clarify the communication principles in this ISA? Q. Does the IAASB agree with the further guidance provided in paragraph A22 in the revised draft in relation to treating the requirement to communicate to management as having been discharged at the time the auditor first discusses the identified deficiencies with management? I. Deficiencies Involving Management 66. Paragraph 9(b) of the ED proposed that the auditor be required to communicate all nontrivial deficiencies identified during the audit to management unless it would be inappropriate to communicate directly to them in the circumstances. Para A13 of the ED proposed guidance on circumstances when it may be inappropriate to communicate directly to management. 67. Several respondents26 noted that the ED did not explain what the auditor should do in those circumstances. In addition, they questioned whether these matters should be treated as significant deficiencies. Some of them suggested that it would be helpful to include a reference to ISA 250 (Redrafted)27 in relation to the requirement for the auditor to report management’s non-compliance with laws or regulations to those charged with governance. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 68. 26 27 The Task Force agreed that guidance should be provided as to the action the auditor should take if it is inappropriate to communicate deficiencies involving management directly to management. The Task Force is of the view that such deficiencies should be treated as significant deficiencies by definition because they would always merit the attention of those charged with governance. Given this presumption, the auditor should then be under an obligation to communicate these deficiencies to those charged with governance, as required ACAG, Basel, CAPB, CEBS, FEE, GT, ICAEW, IRBA and IRE. ISA 250 (Redrafted), “Consideration of Laws and Regulations in an Audit of Financial Statements.” Agenda Item 3-A Page 18 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1721 by the ED. The Task Force also agreed that a reference to ISA 250 (Redrafted) would be appropriate in relation to describing management’s non-compliance with laws or regulations as one type of deficiency involving management that it would be appropriate to communicate to those charged with governance. 69. Accordingly, the Task Force proposes that guidance be provided in paragraph A16 to explain these points. J. Follow-up by the Auditor on Deficiencies Communicated in the Prior Period 70. A respondent (DTT) noted that ED-ISA 265 was not clear regarding the auditor’s responsibility to follow up in the current year on deficiencies or significant deficiencies identified and communicated in the prior year. The respondent suggested that guidance on this matter be provided in the application material. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 71. The Task Force believes that following up on deficiencies identified and communicated in the prior period is an implicit part of the auditor’s risk assessment procedures under ISA 315 (Redrafted). In particular, paragraph 9 of ISA 315 (Redrafted) requires that “when the auditor intends to use information obtained from the auditor’s previous experience with the entity and from audit procedures performed in previous audits, the auditor shall determine whether changes have occurred since the previous audit that may affect its relevance to the current audit.” The Task Force nevertheless believes that a clarification to ISA 315 (Redrafted) would be appropriate in this regard. 72. Accordingly, the Task Force proposes that a conforming amendment be made to the guidance to that requirement as follows: Information Obtained in Prior Periods A10. The auditor’s previous experience with the entity and audit procedures performed in previous audits may provide the auditor with information about such matters as: 73. Past misstatements and whether they were corrected on a timely basis. The nature of the entity and its environment, and the entity’s internal control (including deficiencies in internal control). Significant changes that the entity or its operations may have undergone since the prior financial period, which may assist the auditor in gaining a sufficient understanding of the entity to identify and assess risks of material misstatement. Extant paragraph A11 of ISA 315 (Redrafted) then explains the need for appropriate follow-up: A11. The auditor is required to determine whether information obtained in prior periods remains relevant, if the auditor intends to use that information for the purposes of the current audit. This is because changes in the control environment, for example, Agenda Item 3-A Page 19 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1722 may affect the relevance of information obtained in the prior year. To determine whether changes have occurred that may affect the relevance of such information, the auditor may make inquiries and perform other appropriate audit procedures, such as walk-throughs of relevant systems. K. Illustrative Reports 74. A respondent (EY) suggested that illustrative report wording would be helpful, particularly in relation to the requirement and guidance in paragraphs 11(b) and A19 to A21 of the ED regarding the content of the written communication. Preliminary Task Force Views and Recommendations 75. The Task Force is of the view that illustrative wording for the written communication would be unnecessary given that the principles regarding the content of the written communication, as set out in paragraph 11(b) of the ED, are quite clear. Further, firms should be given flexibility to draft their own written communications using their own styles appropriate to the circumstances of their local environments. Indeed, there would be a risk that any illustrative wording in the ISA would become a de facto reporting standard, which would be contrary to the principle that such communication be simply a by-product of the audit. Agenda Item 3-A Page 20 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1723 Appendix List of Respondents Abbreviation Name Professional Organizations AIA Association of International Accountants AICPA American Institute of Certified Public Accountants ACCA The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants CALCPA California Society of Certified Public Accountants CIPFA Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy CAGC Certified General Accountants, Canada CNCC Compagnie Nationale des Commissaires aux Comptes (CNCC) and the Conseil Supérieur de l’Ordre des Experts-Comptables (CSOEC) DnR Den norske Revisorforening FEE Fédération des Experts Comptables Européens FICPA Florida Institute of Certified Public Accountants HKICPA Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants ICAI ICAP ICAS ICJCE IDW ICPAK ICPAS Institute of Chartered Accountants in Ireland Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland Instituto de Censores Jurados de Cuentas de España Institut der Wirtschaftsprufer Institute of Certified Public Accountants of Kenya Institute of Certified Public Accountants of Singapore ICABC Institute of Chartered Accountants of British Columbia ICAEW The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales IIA Institute of Internal Auditors IRE Institut des Réviseurs d’Entreprises JICPA The Japanese Institute of Certified Public Accountants SAICA The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants National Auditing Standard Setters APB UK Auditing Practices Board CICA Auditing and Assurance Standards Board of the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants IRBA Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (also a Regulator) NZICA Professional Standards Board of the New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants Firms BDO BDO Global Coordination B.V. BTR Baker Tilly Russaudit Ltd DTT Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu EY Ernst & Young Global Agenda Item 3-A Page 21 of 22 Control Deficiencies – Significant ED Comments IAASB Main Agenda (September 2008) Page 2008·1724 Abbreviation Name GT Grant Thornton International KPMG KPMG PwC PricewaterhouseCoopers Public Sector Organizations ACAG Australasian Council of Auditors-General OAGNZ Office of the Controller and Auditor-General of New Zealand SNAO Swedish National Audit Office UKNAO UK National Audit Office USGAO US Government Accountability Office WAO Wales Audit Office Regulators and Oversight Authorities Basel Basel Committee on Banking Supervision CEBS Committee of European Banking Supervisors CPAB Canadian Public Accountability Board EC European Commission Individuals and Others JM Dr. Joseph Maresca CPA, CISA EFAA European Federation of Accountants and Auditors for SMEs EI European Issuers Agenda Item 3-A Page 22 of 22