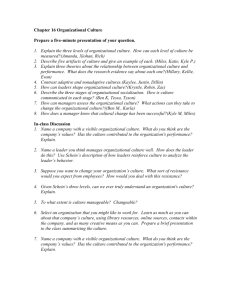

LEADERSHIP – THE PRIVILEGE OF THE FEW OR INHERITANCE

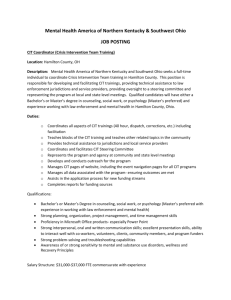

advertisement

LEADERSHIP – THE PRIVILEGE OF THE FEW OR INHERITANCE OF THE MANY? Squadron Leader P K O’Donnell OC FDS, RAF Lossiemouth Within the diverse and increasingly crowded arena of leadership debate the notion of ‘distributed’ leadership is attracting considerable interest. Also travelling under the pseudonyms: ‘dispersed’ and ‘informal’ leadership, its emergence caught the interest of eminent M.I.T. professor, Edgar H Schein, who predicted in 1996 that, ‘Perhaps the most salient aspect of future leadership will be that [it] will not be present in a few people all of the time but will be present in many people some of the time as circumstances change...Leadership will then increasingly be an emergent function rather than the property of people appointed to a formal role.’1 Within this short statement, Schein has embedded two premises in support of his assertion that increasingly the leadership function will be embodied within more people for shorter periods of time. The first of these is his prediction that the leadership role will adopt a peripatetic quality, moving from person to person concomitant with prevailing circumstances. The second, almost a corollary of the first, is that leadership will be an emergent function rather than a preordained organizational role. The humble aspiration of this paper is to make a small contribution to the wider leadership debate by conducting a brief exploration of the premises underpinning Schien’s assertion. However, before a meaningful discussion can take place, it is necessary to give shape to the idea of leadership. This paper opens, therefore, with a short discourse on the nature of leadership in order to place in context the subsequent discussion over where and by whom that leadership is exercised. ‘The final test of a leader is that he leaves behind him in other men the conviction and the will to carry on.’2 Plato’s Theory of Ideas introduced the concept that outside of time and space existed the ‘ideal’ of everything; he suggested that it is the idea that is real whilst the particular, that which we encounter in our daily lives, is merely apparent. For example, consider a horse. The term ‘horse’ refers not to a particular horse but to horses in general. If a three-legged horse were observed, it would still be recognised for what it is, despite its being somewhat removed from the ideal. The search for an understanding of the idea of leadership is much the same. When confronted by leadership, it is eminently recognisable – despite its holding a form that may be far from the ideal. Charles Handy described the search for the definitive solution to the leadership conundrum as being, ‘…another endless quest for the Holy Grail.’ 3 It could be that the definitive solution has remained so evasive because researchers and commentators have sought to mould particular examples of leadership into an ideal, only to be frustrated that their work has limited utility. Leadership cannot exist in the abstract, it must occur in relation to, or as a response to something. It is unsurprising that none of the various trait, style or contingency theories has received unanimous acceptance and that the debate over whether leadership is trainable or innate remains unresolved; for leadership finds its meaning through its interaction with the environment.4 In this context, environment is not restricted simply to ecology but to all of the constraints and opportunities under which leadership is exercised. Indeed, Schein concurs by noting that, together with the nature of the task and subordinates’ characteristics, ‘One of the most consistent findings by historians, sociologists and empirically oriented social psychologists is that what leadership should be depends on the particular situation...’ 5 McGregor provides further support through his assertion of, ‘...leadership as a relationship between the leader and the situation [rather] than as a universal pattern of characteristics possessed by certain people.’ 6 It is not the intention of this paper to be seduced into the debate over what characteristics or qualities a leader ought to possess. Equally, views over what constitutes ‘good’ leadership are avoided as this has as much to do with the characteristics of the perceiver as it does with the leader. More important here is a general understanding of the function of leadership. 1 Kotter is unequivocal, ‘Leadership produces change. That is its primary function.’ 7 He separates the notion of management, which he suggests is, ‘about coping with complexity’, from leadership, which is ‘coping with change.’ 8 The differences in function are subtle yet profound. Managers, he contends, conduct the deductive process of planning which is designed to produce orderly results; leaders, however, are involved with the inductive process of setting direction based upon gathering data and seeking patterns. Bennis’ famous conclusion that, ‘the manger does things right; the leader does the right things’ 9 no longer seems an adequate distinction. Much more compelling is the proposition that the manager supports the status quo, whilst the leader determines and facilitates change. Butcher and Meldrum’s pronouncement of ‘leadership-as-change’ support a more contemporary view. 10 To Schein, leadership and culture are interdependent to the extent that neither can be understood independent of the other. 11 He agrees that leadership and change are inter-linked, yet adds a cultural dimension, ‘…one can argue that leaders create and change culture, while managers and administrators live with them.’12 Notwithstanding the title of the individual performing the leadership function: manager, leader, commander, or co-ordinator, there will, nevertheless, be a need in all organizations for what Charles Handy calls ‘linking-pins’.13 Leaders act to hold the organization together, to provide direction and to articulate change. This is not a singular activity, but is dependent upon the shape and nature of the organization as well as the people that comprise it. In his speech to the Windsor Leadership Trust, David Varney, former CEO of the BG Group, opined that leadership also ‘…exists to create a collective effort’, he went on, ‘Leaders foster a growth environment and a culture that enhances the ability and the willingness of the people within it to achieve. 14 Although this has been but a brief foray into the nature of leadership, it provides a backdrop to the ensuing discussion over whether, increasingly, the leadership function will be embodied within more people for shorter periods of time. The nexus between leadership and the environment provides a clue to where leadership may be found. That it exists to bring about change to spur organizations towards improvement is what leadership does. These are merely reflections of the idea of leadership, the full answer is well outside of the scope of this short paper; indeed, Plato might have argued that it can be found only in the metaphysical. ‘Bureaucracies are strong on permanence but weak on political leadership. Every bureaucrat wants to do tomorrow what he did yesterday.’15 Over recent years, organizations have witnessed enormous change to both their internal and external environments. Change itself is not new. History attests to political and industrial changes that have been so profound as to be categorized as revolutions. It is the pace of change as well as a sense of its being ineluctable that places the modern phenomenon in its own class, causing some to conclude that ‘…perpetual learning and change will be the only constant.’16 At its vanguard has been technological innovation and its wake an explosion in the quantity of information. The result has been significant sociological and psychological transformations that have impacted on every level of society, from individual to global. In response, effective organizations are becoming an orchestration of ‘...large numbers of selfcontained clusters which may be called projects, business units, task forces etc.’ 17 Indeed, it is estimated that today only twenty percent of an organization’s employees are full-time.18 Contractors, suppliers, and external professionals now conduct the remainder of the organization’s activities. A consequence is that smaller autonomies now work in collaboration to produce an output that was once within the purview of an individual firm. However, autonomy does not mean isolation; indeed, within and without the organization, interdependence will be a central feature that ties employees to others. 19 Spurred by the Internet, organizations can now operate globally, not only in terms of marketing but also at a functional level. There is a growing tendency for individuals and small business units to work at dispersed locations, some of which may even work within a ‘virtual organization’. 20 As ‘knowledge workers’21 replace labourers, to speak of organizational hierarchies is becoming anathema. Related to this has been an increase in employee expectations combined with ‘...a need for greater meaning in their work lives.’22 2 Such organizational and sociological transformation has fuelled the debate over the place of the leadership function. If one accepts that the pace of change is likely to continue to escalate and that leadership is central to that change, a natural deduction is that in the future there will be a need for even more leadership.23 However, it seems unlikely that there will be much change to the leadership role at top of organizations. David Varney, drawing on his considerable experience, opined that the one thing which has not changed is, ‘...the overarching role of leadership.’ 24 Handy contributes from academia by differentiating between leadership in the middle of an organization and that at the top where, ‘...it has to be personalized...’ 25 Schein corroborates by submitting that for meaningful change to occur, it would ‘probably’ be necessary that the leadership function were embodied in a CEO or similar senior manager. 26 However, there is considerable debate surrounding the leadership function at the middle level of organizations. As autonomous and semiautonomous units increasingly characterize the organizational midlevel, one could argue that direct hierarchical control has become less relevant. In its stead is a greater encumbrance on higher-order leaders to motivate others throughout the organization to also adopt a leadership role. According to Kotter, this will be essential because, ‘...coping with change in any complex business demands initiatives from a multitude of people.’27 A model for how leadership within these multitudes might be achieved is offered by the notion of ‘distributed’ leadership. The philosophy assumes that not all of the leadershipdefining characteristics will be found within one individual; instead, these qualities will be distributed throughout the team with individuals being called upon to take the lead when their own talents match the needs of the situation. 28 The leadership role is therefore not a formal position but one that will emerge in response to the demands of a situation. Barry postulates that this may be the only acceptable approach to leading groups of highly educated, selfmotivated specialists within organizational structures such as self-managed teams.29 In essence, the worth of distributed leadership is found in its flexibility, which is borne of its responsiveness to the needs of the task, group and environment. In theory, the notion of distributed leadership supports both propositions: that in the future there will be more leadership and that it will be an emerging function. However, far from providing a panacea, it is argued that the distributed leadership model has utility only within self-managed teams established for projects, problem solving, and policy making.30 Furthermore, the model does not make it clear where responsibility lies. Perhaps, but by no means explicit, is a concept of group responsibility or even an absence of responsibility. However, outside of the most egalitarian of non-profit organizations, the probability is that responsibility or accountability will rest somewhere; if it is not found within the team then it can be assumed to be outside of it. One might conclude that the distributed leadership model simply empowers groups of subordinates to operate under the purest form of delegation. That a non-interventionist senior has given the team leave to indulge in self-management does not necessarily mean that its members perform a leadership function. Moreover, if the ultimate role of leadership is to bring about change, one ought not to be surprised when it is not found in the organizational body. Yet recent research suggests a counter view. Jon Katzenbach and his team found that, ‘If you get a critical mass of real change leaders in the middle, you have a much better chance of leading a successful major change effort.’31 They further contend that merely having a committed top team is not enough. In a seminal text32, Professor Ralph Stacey offers an alternative perspective. Although coining the term ‘extraordinary management’, in many respects he describes a function that is very similar to the idea of leadership presented in this paper. He characterizes it as being, ‘...the use of intuitive, political, group learning modes of decision – making and self organising forms of control in open-ended change situations,’33 an open-ended change situation being one in which the outcome is not known or cannot be predicted. He criticises the majority of strategic management textbooks for nourishing the received opinion that successful organizations exist in states of stability and harmony. If that were the case there would be no need for managers (leaders), for their existence is justified by situations that arise outside of a plan. In the future, organizational survival will hinge on an ability to undergo cataclysmic paradigm shifts; this in turn will necessitate extraordinary management (leadership) at every level.34 Consequently, 3 leadership activity is likely to occur in intensive bursts, will have to be highly sensitive to emerging situations, and could emanate from anywhere within the organization. According to Stacey, change is likely to occur instantaneously and without warning; it thereby undermines the worth of long-term planning. Naturally, there is an opposing view. By not developing a long-term plan with associated strategic direction, leaders at the top of the organization would be abrogating their responsibilities.35 Also, with escalating numbers of sub-cultures and quasi-autonomies acting in concert, someone has to act as conductor; the concomitant role of organizational heads as the focus for activity and the linchpin that holds together these loose collectives is, therefore, increasingly important. In addition, the decimation of organizational levels witnessed throughout the 1980s and 90s further intensifies the need for effective leadership at the top whilst reducing the requirement for midlevel leaders. Advances in real-time communications manifested in the seemingly ubiquitous Internet have facilitated a reversal in some organizations’ de-centralist policies. In 2001, Oracle’s CEO was able to report that adopting a centralized system had enabled it to exceed its $1 billion annual savings target. 36 The demise of its erstwhile semi-independent international areas also evidenced a diminution in the number of leaders required in that industry. The Internet will continue to impact on the shape and size of organizations, as well as interorganizational relationships. In his speech to the World Bank Government Borrower’s forum in 200037, David Hayden described the Internet’s growth as being ‘inexorable.’ He estimated that in the space of 5 years the global economy will have increased from less than $70 trillion to over $110 trillion, of that over 10% will be online whereas it was currently less than 2%. The enormity of this change will alter the way business is conducted and the organizational structures that enable it. Whether there will be more or fewer leaders occupying formal or emerging positions, one thing seems certain: the Internet will be central to the outcome. “The sobering truth is that our theories, models, and conventional wisdom combined appear no better at predicting an organisation’s ability to sustain itself than if we were to rely on random chance.”38 This paper has expounded the centrality of environment to leadership, a function that is justified when it brings about change. Organizations of all types have witnessed profound changes to their working practices; technological innovation as well as societal and political demands has driven much of this. Collectives, working under the umbrella of one or more parent organizations have necessitated a restructuring of organizational hierarchies as well as a review of the leadership roles within them. There is a consensus to the continuing need for effective leadership at the top of organizations. Indeed, in terms of engendering a sense of leadership within the component business units and providing coherence to their collective effort, the role is likely to become even more demanding. However, the position of leadership in other parts of the organization is less clear. Schein’s prediction that future leadership will be present in many people some of the time as circumstances change and that it will be an increasingly emergent function seems overly general and somewhat dogmatic. The application and distribution of leadership will depend upon factors such as the nature of the organization, its life cycle, and its internal and external environments. The discussion has necessarily been confined to those aspects of leadership that are immediate to the debate. However, this short sojourn into what is regarded as the most widely researched yet least understood area of organizational behaviour has provided an exposition of the complexity of the subject. There is neither snappy sound bite nor shallow generalization with which to conclude. The twenty-first century will be the beneficiary of magnificent change, some of which cannot yet be imagined. Leaders throughout all organizations, will adapt, respond, but above all else be responsible for this change. Some will find success through a distributed leadership system, others within a formalized hierarchy, and others still within a virtual domain. ‘Ah well! I am their leader, I really had to follow them!’39 4 References Schein, E. H. ‘Leadership and Organizational Culture’, in Hesselbein, F., Goldsmith, M. and Beckhard, R. The Leader of the Future, (Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1996), p68 2 New York Tribune, 14 April 1945 3 Handy, C. Understanding Organizations, Ed 4, (Penguin Books Ltd, 1999), p97 4 Ibid. p117 5 Schein, E. H. Loc. cit. 6 McGregor, D. ‘The Human Side of Enterprise’, (McGraw-Hill, 1960), cited in Kennedy, C. Managing with the Gurus, (Century Business Books, 1996), pp104 - 105 7 Kotter, J. P. ‘A Force for Change’, (The Free Press, 1990, cited in Kennedy, C. Managing with the Gurus, (Century Business Books, 1996), p109 8 Kotter, J. P. ‘What Leaders Really Do’, Harvard Business Review, May-June 1990, p104 9 Bennis, W. ‘On Becoming a Leader’, (Hutchinson, 1989), cited in Kennedy, C. Managing with the Gurus, (Century Business Books, 1996), p107 10 Butcher, D and Meldrum, M. ‘Defy Gravity’, People Management, 28 June 2001, pp40 - 42 11 Schein, E. H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, Ed 2, (Jossey-Bass, 1997), p5 12 Loc. cit. 13 Handy, C. Understanding Organizations, Op. cit., p 96 14 Varney, D. ‘Personal Reflections on Leadership: Achieving Sustained Superior Performance’, Vital Speeches of the Day, Vol. 67 Iss. 10, 1 Mar 2001, pp313-317 15 McClelland, J. S. A History of Western Political Thought, (Routledge, 1996), p755 16 Schein, E. H. ‘Leadership and Organizational Culture.’ Op. cit., p67 17 Mills, D. Q. ‘Rebirth of the Corporation’, (Wiley, 1991), cited in Handy, C. Understanding Organizations, Op. cit., p261 18 Handy, C. ‘The New Language of Organizing and its Implications for Leaders’, in Hesselbein, F. et al, op. cit., p7 19 Kotter, J. P. ‘What Leaders Really Do’, Op. cit. p105 20 Handy, C. ‘The New Language of Organizing and its Implications for Leaders’, in Hesselbein, F. et al, op. cit., p6 21 Handy, C. Understanding Organizations, Op. cit., p 348 22 Manz, C and Sims, H P. ‘Superleadership: Beyond the Myth of Heroic Leadership’, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 19, No, 9, 1991 23 Kotter, J P. ‘What Leaders Really Do’, Op. cit., p104 24 Varney, D. Loc.cit. 25 Handy, C. ‘The New Language of Organizing and its Implications for Leaders’, in Hesselbein, F. et al, op. cit., p7 26 Schein, E. H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, op. cit., p382 27 Kotter, J. P. ‘What Leaders Really Do’, Op. cit. p109 28 Barry, D. ‘Managing the Bossless Team: Lessons in Distributed Leadership’, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1991, p34 29 Ibid., p31 30 Ibid., p35 31 Katzenback, J., Beckett, F., Dichter, S., Feigen, S., Gagnon, C., Hope, Q. and Ling, T. Real Change Leaders, (Nicholas Brealey Publishing Ltd, 1997), p331 32 Stacey, R. D., Strategic Management & Organisational Dynamics, Ed 2, (Pitman Publishing, 1996) 33 Ibid., p73 34 Ibid, pxix 35 Gaddis, P. O. ‘Strategy Under Attack’, Long Range Planning, Vol. 30, No. 1, 1997, pp38-45 36 Ellison, L. ‘Leading e-Business’, Executive Excellence, Vol. 18, Iss. 3, Mar 2001, pp2-4 37 Hayden, D. ‘The Internet is a Domain of Thinking and Acting: Leadership in the E-Commerce Revolution’, Vital Speeches of the Day, Vol. 66 Iss. 6, 1 Jun 2000, pp496-500 38 Pascale, R. Managing at the Edge, (Penguin Books, 1990) 39 de Mirecourt, E. ‘Ledru-Rollin’, Les Contemporains, Vol 14, 1857 (Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin (1807-74), French politician) 1 5