DESIGN PROCESS AS A PART OF NEW PRODUCT

advertisement

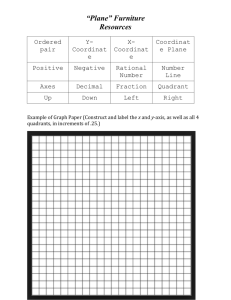

DESIGN PROCESS AS A PART OF NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT – CASE FURNITURE INDUSTRY Päivi Haapalainen*, University of Vaasa, Finland paivi.haapalainen@uwasa.fi, *corresponding author Martti Lindman, University of Vaasa, Finland martti.lindman@uwasa.fi ABSTRACT Time-based competition, first-mover advantages and a fast product development cycle time are some of the strategies used in order to gain competitive advantage in the current fastchanging competition environment. New product development (NPD) is one of the key components when implementing these strategies. Design process lies in the core of NPD, especially in the furniture industry. This paper aims at depicting the design process and the prerequisites to it being both fast as well as successful. The design process is seen as an interaction process between the designer, the entrepreneur and prototype makers. The process depiction and other results are also compared to some main NPD processes suggested in the reference literature. Three kinds of new products and related NPD processes are discussed: high tech products, low tech products with large innovations and low tech products with small innovations. This paper is based on empirical qualitative research conducted by observing and interviewing several designers and entrepreneurs in the Finnish furniture industry during the autumn of 2010. Some interesting observations have been made. It seems that the designer and the entrepreneur often see the design process in a different way: the designer feels that he should get a good picture of the company, its goals and strategies as well as current products before starting the design work whereas the entrepreneur expects the designer to create something new, more ‘out of nowhere’. This may result in products that do not suite the company thus wasting precious time. Keywords: New Product Development (NPD), design process, furniture industry INTRODUCTION Delivering a product to a customer rapidly can bring a company clear competitive advantage and the furniture industry makes no exception to this (Tammela, Canen and Helo 2008). Good quality and a low price are taken more and more for granted and this turns the focus to time (Wilding and Newton 1996). However, it is not only the actual delivery of a product to a customer being fast that can bring competitive advantage to a company but, also, bringing new products to the market quickly is important. A company developing products faster than its competitors may benefit by getting higher prices, more loyal customers, and a greater market share (Langerak and Hultink 2005). Time-based competition, first-mover advantages and fast product development cycle time are some strategies and tools for gaining these advantages. The concept of time-based competition (also called time-based performance) was introduced by Stalk in the late 1980s. In this strategy, time is seen as a resource that should not be wasted any more than any other resource. The idea of time-based competition is to reduce the cumulative lead time of a product and thus gain competitive advantage. The cumulative lead time includes various processes throughout the organisations, e.g. new product development (NPD), production, procurement, sales, and transportation. (See e.g. Tammela et al. 2008; Vickery, Dröge, Yeomans and Markland 1995.) Research in first-mover advantage or pioneering advantage shows that the first company to enter a new market often gains larger market share than companies coming to the market later. It has been noted that this applies to different situations: consumer and industrial markets as well as growing and saturated markets. (Kardes, Kalyanaram, Chandrashekaran and Dornoff 1993; Michael, 2003.) ‘Fast product development cycle time’, ‘rapid product development’, and ‘new product development speed’ are all terms that refer to attempts to speed up the product development process in order to gain competitive advantage. These concepts mean generally how fast a company can turn an idea into a product in the market place. (Chen, Damanpour and Reilly 2010; Gupta and Souder 1998.) Vickery et al. (1995) have been investigating time-based competition in the furniture industry. Historically this industry has often been connected to long delivery times. However, competition has also forced companies in this business to try to find ways of attracting more customers. Vickery et al. (1995) discovered that the product development cycle time was the sole predictor for market share in comparison to the new product introduction time, production lead time and delivery speed. In industries like the furniture industry design lies in the core of the new product development process. There are various definitions for ‘design’ in the literature. Keeping the furniture industry in mind, this paper uses the definitions of Walsh, Roy and Bruce (1988): “[design is] the configuration of elements, materials and components that give a product its particular attributes of function, appearance, durability, safety and so on” and Ulrich and Pearson (1998): “product design is the activity that transforms a set of product requirements into a specification of the geometry and material properties of an artifact”. Gupta et al. (1998) state that effective design is important to companies for various reasons. First, even though the cost of design may only be less than 10% of the whole costs of the NPD process, the decisions made in this phase determine as much as 80% of the total NPD costs. Secondly, making changes at this point is much cheaper than making changes during the actual production. Furthermore, customer satisfaction often depends on how well the product is designed. This paper focuses on the design process part of new product development in the furniture industry. The objective is to depict the design process and the prerequisites to it being both fast as well as successful. Successful in this case means that the product should meet the end customers’ needs, suite the manufacturing company’s strategy and be effective to produce by the company. This paper is built as follows: theoretical background of new product development in general and some new product development models are introduced in the next chapter. This is followed by the introduction of the empirical research as well as its results. At the end of the paper the findings are discussed in comparison with the theory introduced earlier. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND New product development Amount of innovation Product development has to be done within all industries. However, the nature of the industry (high tech vs. low tech) and the amount of innovation (incremental improvement vs. radical improvement) affects the product development process a great deal (see Figure 1.). Electronics and computers are examples of high tech industries whereas the furniture industry represents low tech industries. Banbury and Mitchell (1995) define incremental innovation as “refinements and extensions of established designs”. Compared to incremental innovations, radical innovations aim at bringing about something totally new either from a technological or some other point of view (Verganti 2006). While product development in high tech industries concentrates on technological innovations and following the rapid changes in technologies (Datar, Jordan, Kekre, Rajiv and Srinivasan 1996) the strategies in low tech industries have to be different. Typically in the furniture industry the main emphasis is on shapes, materials and ergonomics and sometimes, as Verganti (2008) presents, radical innovations are searched for in meanings. Radical improvement Incremental improvement Low tech High tech The nature of industry Figure 1: Different cases of product development. Fast product development cycle or time to market is considered an important source of competitive advantage especially in industries in which product life cycles may be even less than two years (Datar et al. 1996) but also in various other industries (see e.g. Vickery et al. 1995). Chen et al. (2009) list a number of antecedents that have an effect on new product development speed. These antecedents are goal clarity, process concurrency, iteration, team leadership, team experience, team dedication and internal integration. Menon, Chowdhury and Lukas (2002: 324) on the other hand emphasise the learning perspective: “change, flexibility, dynamism, cooperation, invention, innovation and information utilisation should be embraced” in order to gain rapid product development. Product development models Generic product development process Ulrich and Eppinger (1995) have introduced a five-phase product development process model (see Figure 2) that has influenced both academic discussion and practices in companies. The model provides tasks for each phase and also the responsibilities of the different functions of the organisation in different phases. A product development process is defined as “the sequence of steps or activities that an enterprise employs to conceive, design, and commercialise a product” (Ulrich et al. 1995: 14). Phase 1 Concept development Phase 2 Systemlevel design Phase 3 Detail design Phase 4 Testing and refinement Phase 5 Production ramp-up Figure 2: Product development process (Ulrich et al. 1995: 9). In phase 1 “Concept development” new product ideas are created based on the needs of the target market. A number of concepts are then created based on these ideas. Finally, one concept is selected for further development. A concept does not only include description of the product but also deals with market potential, competition and economical issues. In the second phase “System-level design” the product is broken down into smaller subsystems and components. Strong emphasis is also on the actual production or assembly process. (Ulrich et al. 1995.) The next phase “Detail design” takes the process even deeper. All the unique parts of the product are defined in detail: specifications of geometry, materials and tolerances are prepared. Standard parts to be purchased are identified and detailed plans for parts to be manufactured are made. In phase 4 “Testing and refinement” the product is tested from various points of view. Alpha prototypes are intended for making sure that the design works and satisfies the customer. The objective of beta prototypes is to assure that the performance and reliability of the final product is sufficient. (Ulrich et al. 1995.) The final phase “Production ramp-up” aims at preparing for the actual production. The production process is refined and workers are trained. At some point the ramp-up phase turns into full production and the product is launched to customers. (Ulrich et al. 1995.) Stage-gate model The stage-gate model seems to be the most common product development model used by companies. According to Cooper and Edgett (Cooper and Edgett 2005: 133) about 54 % of businesses use it properly with well defined stages, gates and activities but the number of companies that have some sort of stage-gate model in use is even higher. The stage-gate model is based on years of academic research with a large number of new product development projects. The first versions of the model were introduced in the beginning of the 1980s and since then it has been further developed to suit different companies and various situations. (Stage-Gate® is a registered trademark of the Product Development Institute Inc.) (Cooper et al 2005.) The stage-gate model can be considered both a philosophy as well as an operation model for product development. The main idea is to turn product development into a well-structured process with clear and well-defined stages (to go through certain activities) and gates (to make a go/kill decisions). At each gate a project may be terminated. The model consists of six stages and five gates (see Figure 3). (Cooper et al. 2005.) Gate 1 Stage 0 Stage 1 Gate 2 Stage 2 Gate 3 Gate 4 Stage 3 Stage 4 Gate 5 Stage 5 Figure 3: Stage-gate model (modified from Cooper et al. 2005: 140). The stage 0 “Discovery” is for creating/finding opportunities and new product ideas. Based on the decision at gate 1 only some ideas will continue further. The stage 1 “Scoping” means preliminary research that will quickly provide information about the opportunity/product idea which will help make the decision at gate 2. In stage 2 “Build the Business Case” further investigation is done and this leads to product definition, project justification and a project plan. This investigation is carried out on both market as well as technical aspects. This stage is again followed by a gate that will determinate some of the projects. Stage 3 titled “Development” deals with the actual design and development of the product (or even service). Some testing should also be included in this stage. If the product still has potential enough it will pass gate 4 and continue to stage 4 titled “Testing and Validation”. And finally, after gate 5 only some products go on to stage 5, “Launch”. (Cooper et al. 2005.) It is important to note that also the stage-gate model is a general model in the sense that it does not provide detailed answers to companies using it. The model gives hints for what to do and ask at each stage but the companies themselves have to modify the model to fit their own business. However, this forces the companies to actually define their new product development process which may lead to improvement. A number of other new product development models can also be found in the literature. For example Peters, Rooney, Rogerson, McQuarter, Spring and Dale (1999) introduce a new product design and development model that includes three parts: pre-design/development, design and development process and post-design development. These parts are divided into six phases: idea, concept, design, pre-production validation, production/distribution and postcompany. This model is different to the two models presented before in the sense that it links post-design development stronger into product development but otherwise the product development process is fairly similar. EMPIRICAL RESEARCH The research presented in this paper is part of a project called Experimental Design Lab, “EDEL”. The main purpose of EDEL is to create and test new ways of working for the Finnish furniture industry. One way of achieving this is to bring professional designers and manufacturing companies to work together stronger than before. This paper is based on qualitative research conducted by observing and interviewing several designers and entrepreneurs in the Finnish furniture industry during autumn 2010. A total of 8 designers were given a task to design a piece of new furniture based on a brief. Three of the designers have industrial designer qualifications and the rest are interior architects. The briefs used are as follows: a social kitchen as the heart of the home, a bedroom for senior citizens and a home office. The designers spent about four weeks in a small village in Western Finland (in periods of 1 to 2 weeks at the time) so the researcher had a possibility to observe their work and discuss with them several times. Observations were also made when the designers met with the representatives of local furniture companies and interacted with joiners. All the designers were also interviewed. A semi-structured interview was used so that the designers would have the possibility to freely describe the design process as well as their work. The themes used in the interviews included: the road through which the person became a designer the design process (e.g. starting the process, inspiration, co-operation and interaction with the furniture company) ideal way of working vs. reality In addition to the designers the researcher also discussed with several representatives of furniture companies. The objective was to illustrate the new product development processes used in the companies. RESULTS A process chart of the actual design process was drawn based on the discussions with the designers (see Figure 4). The design process is, in this case, limited to the part of the product development process the designer is mainly responsible for. This is the part of product development in which the appearance, materials as well as function(s) of a piece of furniture are decided. Although each designer has a unique approach to design work, the design process itself seems to often be fairly similar. The process begins with creating ideas. Normally a designer has a brief from the customer, e.g. to design a new dining table for the current line of products or to design a piece of furniture for senior citizens. It is not easy for a designer to point out the source of the idea in a particular case. Designers seem to “collect inspiration” wherever they go and whatever they do and then use this “collection” when they design something. Ideas may come from the nature, professional or other magazines, buildings, people, interesting shapes or colours or just about anything. There are a great number of issues to be considered when a designer is planning a new piece of furniture. One group of issues is related to the use of the furniture: the planned use or multiple ways of using the furniture, the user, non-planned use, and the space in which the furniture might be used. Another group of considerations is related to the furniture itself: shapes, colours, material, and ergonomics are all examples of these issues. Designers also have to consider the production of the furniture: how will it actually be manufactured. The structure and different parts of the furniture are important from this point of view. Sometimes creating ideas involves gathering information. The designer may not possess enough knowledge about e.g. the users or the materials. They may discuss with the representatives of the user group or read some studies about the non-familiar issue. However, the designers say, without this work a good result cannot be reached. Sketches / designs by hand Creating ideas First models Mock-ups Prototypes Sketches/ designs by using computer Figure 4: The design process. The next phase of the design process is to prepare sketches and designs either by hand or by using some computer software. For some designers sketching and creating ideas are one activity and some designers think about the idea first for so long that it is almost ready when they actually begin to draw it. Sometimes a designer makes sketches first by hand and only after that uses the computer to prepare final designs. Moving back and forth between creating ideas and making sketches and designs seems to be typical for the design process. Concrete, three dimensional models or mock-ups are built in the next phase of the process. The designers say that it is sometimes difficult, even for them, to perceive for example the proportions of the finished piece of furniture without actually seeing it and therefore mockups can be built. Sometimes a designer wants to see how the material can be used and models are built for that purpose. Shape, too, can be the reason to build a model and in this case it can be built also of other materials or in another size than the actual furniture. Based on the experience of the models the designer may go back to the previous phase and redesign some parts or the whole piece of furniture. In the final phase a prototype or more is built. The purpose of the prototype is to show what the piece of furniture will look like when produced in the actual size and of the actual material that has been designed. Building a prototype also gives viewpoints for planning the actual manufacturing process. In this phase the designer may need help from someone who builds the prototype – either the customer company or an external party. There are two important things to be noticed about the design process of furniture: 1) it is not a linear process, and 2) the designer should not be left alone with the process. The process does not often move on from one phase to another linearly. It goes back and forth between the phases and sometimes different phases can be carried out simultaneously. This makes it difficult to see how the process is actually proceeding. Even though the designer is responsible for the process, she should not be left alone with it. Strong input from the furniture manufacturing company is needed throughout the process. Designers say that it is important for them to understand the company, its history, strategy and needs. That way they can design something that suits the company. It is also important for the designers to know what the company can produce from a technological point of view. Sometimes there is crucial knowledge about the materials and manufacturing techniques in the company that should be included in the design process. Therefore the design process should be a continuous interaction process between the designer and the company which will make it possible for new product development to be both fast as well as successful. During the discussions with the designers a special case of new furniture development came up: designing totally new, innovative products. All the interviewed designers agreed that this should not/cannot be carried out by the designer alone; instead there should be a crossprofessional team. For example if the objective is to create innovations in the field of furniture for senior citizens, the team might consist of an expert in geriatrics, technological expert(s), representatives of the user group and manufacturing companies in addition to the designer. DISCUSSION The purpose of the design process presented in this paper is not to replace the product development processes introduced earlier. Instead this paper aims at opening up the product development process from the designers’ point of view to the manufacturing company and its management. Good design can bring a competitive advantage to a furniture company and in order to gain this advantage, co-operation is needed. Involvement of both the company and the designer is needed in successful new product development process which is highlighted also by Peters et al. (1999). And the more radical innovations are pursued, the more important it is to have a multi-skilled team. Another objective of this paper is to complement the earlier product development models from the furniture industry’s point of view. The main challenge in combining the design process as the designers have presented it with the earlier product development processes lies in the fact that these product development models are strongly linear: when one phase is finished, you should move to the next and no longer return to previous phases. However, the design process of a piece of furniture is more iterative. Good solutions are searched by a trial and error method. Creating ideas and concepts, designing models and building prototypes are mixed together until the solution is found. Is this because most product development models have their origin in high tech industries and furniture industry is a low tech industry? Or can the reasons be found in the differences of incremental and radical innovations? Perhaps neither of these explains the situation. It is likely that the earlier product development processes have a strong managerial view. And from this viewpoint the important matter is decision-making. The manager might not be so interested in the actual design process (that is hidden somewhere in the phases or stages) but in the results that can be used when deciding whether to continue the process or not. This could also be the viewpoint of a large company where the management might not be so involved in the actual design work. However, it seems that for the manager of a small furniture company the only way to survive might be getting interested and involved in the design process, too. REFERENCES 1. Banbury, C.M. and W. Mitchell (1995). The effect of introducing important incremental innovations on market share and business survival. Strategic Management Journal. 16, 161-182. 2. Chen, J., F. Damanpour and R. R. Reilly (2010). Understanding antecedents of new product development speed: A meta-analysis. Journal of Operations Management. 28, 1733. 3. Cooper, R. G. and S. J. Edgett (2005). New Product Development – Lean, Rapid and Profitable. Product Development Institute. 4. Datar, S., C. Jordan, S. Kekre, S. Rajiv and K. Srinivasan (1996). New product development structures: The effect of customer overload on post-concept time to market. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 13, 325-333. 5. Gupta, A. K. and W. E. Souder (1998). Key drivers of reduced cycle time. Research Technology Management. 41(4), 38-43. 6. Kardes, F. R., G. Kalyanaram, M. Chandrashekaran and R. J. Dornoff (1993). Brand retrieval, consideration set composition, consumer choice, and the pioneering advantage. Journal of Consumer Research. 20(1), 62-75. 7. Langerak, F. and E. J. Hultink (2005). The impact of new product development acceleration approaches on speed and profitability: Lessons for pioneers and fast followers. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 52(1), 30-42. 8. Menon, A., J. Chowdhury, B. A. Lukas (2002). Antecedents and outcomes of new product development speed. An interdisciplinary conceptual framework. Industrial Marketing Management. 31, 317–328. 9. Michael, S. C. (2003). First mover advantage through franchising. Journal of Business Venturing. 18(1), 61-80. 10. Peters, A. J., E. M. Rooney, J. H. Rogerson, R. E. McQuarter, M. Spring and B. G. Dale (1999). New product design and development: a generic model. The TQM Magazine. 11(3), 172-179. 11. Tammela, I., A. G. Canen and P. Helo (2008). Time-based competition and multiculturalism. A comparative approach to the Brazilian, Danish and Finnish furniture industries. Management Decision. 46(3), 349-364. 12. Wilding, R. D. and J. M. Newton (1996). Enabling time-based strategy through logistics – Using time to competitive advantage. Logistics Information Management. 9(1), 32-38. 13. Ulrich, K. T. and S. D. Eppinger (1995). Product Design and Development. New York etc.: McGraw-Hill. 14. Ulrich, K. and S. Pearson (1998). Assessing the importance of design through product archeology. Management Science. 44(3), 352-369. 15. Verganti, R. (2006). Innovating through design. Harvard Business Review. Dec, 114-122. 16. Verganti, R. (2008). Design, meanings and radical innovation: A metamodel and a research agenda. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 25, 436-456. 17. Vickery, S. K., C. L. M. Dröge, J. M. Yeomans and R. E. Markland (1995). Time-based competition in the furniture industry. Production and Inventory Management Journal. 36(4), 14-21. 18. Walsh, V., R. Roy and M. Bruce (1988). Competitive by design. Journal of Marketing Management. 4(2), 201-216.