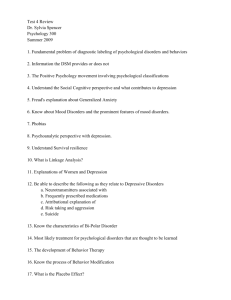

Unit Summary

advertisement