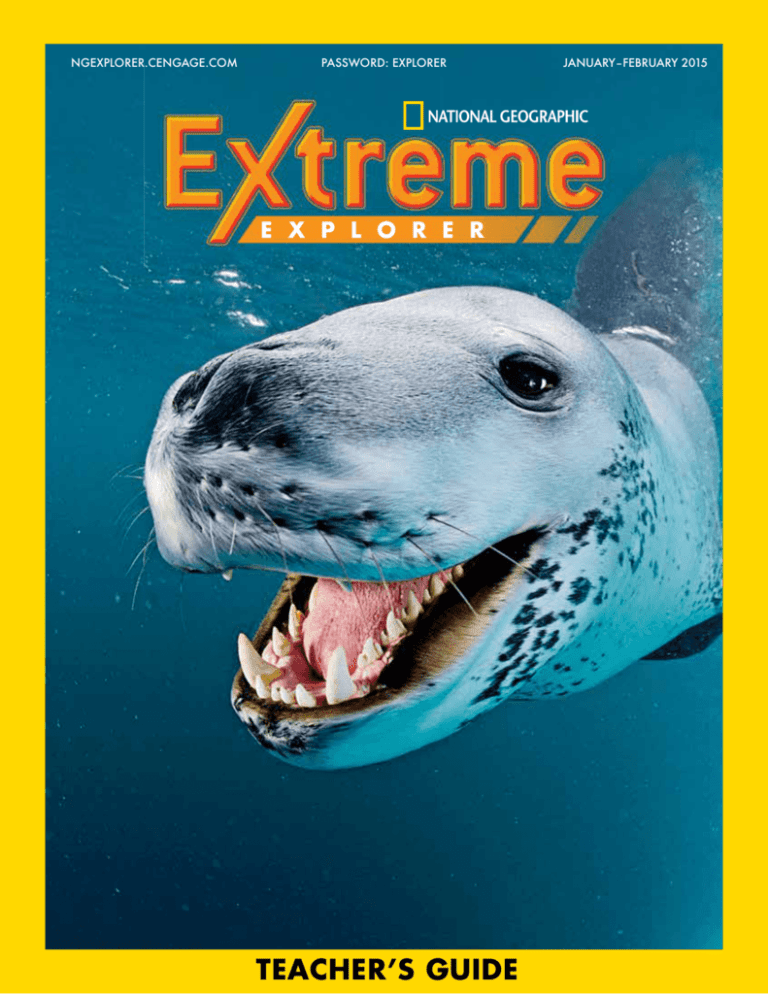

NGEXPLORER.CENGAGE.COM

PASSWORD: EXPLORER

E X P L O R E R

TEACHER’S GUIDE

JANUARY–FEBRUARY 2015

Frozen: Overview

Summary

Next Generation Science Standards

• From the outside, icebergs look like huge chunks

of ice floating in the ocean. In fact, these frozen

environments are teeming with life.

• Many icebergs support a vast food web that spreads

on, under, around, and even inside their icy surfaces.

Marine biologist Gregory S. Stone braved the frigid

waters to learn more about how these food webs work.

Curriculum in This Article

Common Core State Standards

• Analyze how a particular sentence, paragraph,

chapter, or section fits into the overall structure of

a text and contributes to the development of the

ideas. (RI.6.5)

• Analyze the structure an author uses to organize a

text, including how the major sections contribute

to the whole and to the development of the ideas.

(RI.7.5)

• Analyze in detail the structure of a specific

paragraph in a text, including the role of particular

sentences in developing and refining a key concept.

(RI.8.5)

• Draw evidence from literary or informational

texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

(W.6/7/8.9.b)

• S cience and Engineering Practice: Developing and

Using Models

• Disciplinary Core Idea: Cycles of Matter and Energy

Transfer in Ecosystems—Food webs are models that

demonstrate how matter and energy are transferred

between producers, consumers, and decomposers

as the three groups interact within an ecosystem.

Transfers of matter into and out of the physical

environment occur at every level. Decomposers

recycle nutrients from dead plant or animal matter

back to the soil in terrestrial environments or to

the water in aquatic environments. The atoms that

make up the organisms in an ecosystem are cycled

repeatedly between the living and nonliving parts of

the ecosystem.

• Crosscutting Concept: Energy and Matter

Materials Needed

•p

lain white paper, index cards, sentence strips, plastic

bags, a dictionary, a thesaurus, and slips of paper

• Vary sentence patterns for meaning, reader/listener

interest, and style. (L.6.3.a)

• C hoose language that expresses ideas precisely and

concisely, recognizing and eliminating wordiness

and redundancy. (L.7.3.a)

• Use verbs in the active and passive voice and in

the conditional and subjunctive mood to achieve

particular effects. (L.8.3.a)

• Performance Expectation: Develop a model to

describe the cycling of matter and flow of energy

among living and nonliving parts of an ecosystem.

(MS-LS2-3)

• t he Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute's Antarctic

environment interactives at: http://polardiscovery.whoi.

edu/antarctica/ecosystem.html

Additional Resources

• Learn more about Antarctic iceberg ecosystems:

▶http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/

data/2001/12/01/html/ft_20011201.2.html

▶http://archive.audubonmagazine.org/features0901/

To access the projectable edition of this

article, go to the Teacher tab for this

magazine at ngexplorer.cengage.com.

truenature.html

• Build an Antarctic Marine Food Web:

▶http://www.pbslearningmedia.org/asset/lsps07_int_

oceanfoodweb/

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T1

January–February 2015

Frozen: Background

Fast Facts

• An iceberg is a huge chunk of freshwater ice that floats

in the ocean. It forms when a large piece of ice breaks

off from an ice shelf or glacier.

• T

o officially be classified as an iceberg, ice must rise

more than five meters above the ocean and cover an

area of 500 square meters.

• Although icebergs appear barren, they actually support

vast food webs. As in all other food webs, those found

on icebergs begin with energy from the sun. That

energy then transfers through a widening web of

organisms.

• I cebergs are much larger than they appear. Only 10

to 20 percent of an iceberg is visible above the water's

surface.

• Marine biologist Gregory S. Stone studied the nonliving

factors and organisms that make up an iceberg food

web, including:

▶diatoms: single-celled aquatic phytoplankton.

that use photosynthesis to make their own food

and get nutrients from dirt on the iceberg.

• I n the Northern Hemisphere, most icebergs break off

of glaciers in Greenland. Almost all icebergs in the

Southern Hemisphere come from Antarctica.

• Th

e average iceberg exists for three to six years before

it melts.

▶k rill: tiny shrimp-like crustaceans that eat

diatoms and are the primary food source for

many marine mammals and fish.

▶comb jellies: invertebrates that eat krill, small

fish, and even other comb jellies.

▶crabeater seals: the most numerous type of seal

in the world that ironically eat krill—not crabs.

These seals can grow up to 2.5 m long and weigh

up to 400 kg.

▶Adélie penguins: a type of penguin that eats tiny

aquatic animals including krill, fish, and squid.

▶p etrels: seabirds that live near icebergs, the

ice pack, and cold ocean waters surrounding

Antarctica and whose diets include krill, other

small crustaceans, mollusks, squid, and fish.

▶l eopard seals: seals with slender bodies, long

fore-flippers, large heads, and sharp teeth that

are a major predator of young crabeater seals and

penguins.

▶orcas (killer whales): toothed whales that are

apex predators in Antarctic waters, eating fish,

squid, penguins, seals, and other whales. They

are the only natural predator of leopard seals.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T2

January–February 2015

Frozen: Prepare to Read

Activate Prior Knowledge

Vocabulary

1. P

rior to conducting this activity, draw a picture of

1. Prior to conducting this activity, write each Wordwise

Sharing Ideas about Icebergs

Mix and Match to Master Definitions

an iceberg on a piece of plain white paper. Add these

words to your drawing: food, provide, alive, energy,

and ecosystem.

2. G

ive each student a piece of plain white paper.

Instruct students to quickly sketch a picture of an

iceberg. Then challenge them to each think of five key

words related to icebergs. Instruct students to add

those words to their drawings.

3. I nvite students to post their drawings on the board.

As a class, examine and compare the selected words.

How many students wrote words that tell what an

iceberg is (ice), what it's like (frozen), or what it does

(floats)? Point out papers where students chose to take

a different approach. Invite those students to explain

why they chose each word.

4. Th

en display the image you drew. Did students have

any of these words on their drawings? If not, why do

they think you chose these words? Encourage students

to share their thoughts with the class.

word on a separate index card.

2. Display page 6 of the projectable edition. Invite

volunteers to read the words and their definitions

aloud. Lead a class discussion to examine each

definition in as much detail as possible.

3. Divide the class into small groups. Show students

the cards. Explain that you will pick two cards and

read them aloud. Give groups two minutes to write

a sentence that uses both words in a way that tells

what each word means. Use the cards consumer and

producer to provide an example. (A producer makes its

own food, but becomes food when a consumer eats it.)

4. Choose two new cards, and begin the challenge.

After each combination, instruct groups to share

their sentences. Encourage the class to evaluate

each. When you're finished, invite students to share

what they learned about each word.

ELL Connection

Piecing Together Definitions

1. Prior to conducting this activity, write each Wordwise

word and its definition on a sentence strip. Cut the

strips apart so there is one word on each piece. Place

the pieces for each definition in separate plastic bags.

2. Display the Wordwise words on page 6 of the

projectable edition. Review each term with the class.

Then remove the words from one bag. As a class,

rearrange the words in the proper order. Which

definition did students unscramble?

3. Guide students as they unscramble the other three

definitions. Then divide the class into four groups.

Give each group a bag. Have them unscramble the

definition. Then rotate the bags so groups have a

chance to unscramble each definition.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T3

January–February 2015

Frozen: Language Arts

Explore Reading

Explore Writing

1. I nvite volunteers to look up the word structure in a

1. T

ell students to imagine that they're research assistants

Examining Text Structure

Writing About the Ecology of Icebergs

dictionary and a thesaurus. Explore each reference.

Challenge students to explain how the definition and

synonyms relate to a text. Guide them to recognize

that texts are built, just like buildings, organisms, and

systems. And like these other things, texts and their

parts can be built in different ways.

2. D

isplay pages 2-3 of the projectable edition.

Encourage students to guess what the article is

about and some of the main ideas it might address.

Then review the four basic types of text structure:

chronology, comparison, cause/effect, and problem/

solution. Discuss how the writer might use each of

these approaches throughout the article.

2. A

fter the expedition, Dr. Stone plans to write an article

for National Geographic magazine. He wants to be as

thorough as possible, so he's asked his team members

to write a short summary of what they saw and

learned, how the trip changed their ideas about the

ecology of icebergs, and why it changed their ideas.

3. A

ssign each student a partner. Instruct partners to

research the article for content to include in their

summaries. Then tell them to analyze the information

and reflect upon their findings to evaluate how their

views of iceberg ecology changed.

3. G

ive each student an Activity

Master. Assign each student a

reading partner. Based upon

the grade-level priorities below,

challenge pairs to identify,

analyze, and explain parts of

the text. Instruct students to

record this information on

their Activity Masters. Then

rejoin as a class. Invite students

to share and compare their results.

on an expedition with marine biologist Gregory S.

Stone to learn more about the ecology of icebergs.

4. I nvite pairs to share their summaries. Encourage

students to identify key points that caused their

classmates' views to change. Which reasons were

most common? Which made the most sense? Were all

reasons supported with evidence from the text?

Activity Master,

page T6

How and Why to Use Variety in Text

1. I nstruct students to choose a paragraph from the

article and rewrite it as noted below.

Common Core Grade-Level Differentiation

Grade 6:

▶Have students choose one sentence, paragraph,

or section in the article, analyze how it fits into

the overall structure of the text, and explain how

it contributes to the development of the ideas.

Grade 7:

▶Instruct students to identify the overall text

structure, analyze how the major sections

contribute to the whole, and explain how they

contribute to the development of the ideas.

Grade 8:

▶Instruct

students to select one paragraph, analyze

the role of key sentences in that paragraph, and

explain their role in developing and refining a

key concept.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Explore Language

Common Core Grade-Level Differentiation

Grade 6:

▶Limit students to simple sentences with no more

than eight words each. Examine the results to

show why it's important to vary sentence patterns

for meaning, reader/listener interest, and style.

Grade 7:

▶Encourage students use vague language and wordy

or redundant prose. Examine the results. Point

out that this is why writers choose language that

expresses ideas precisely and concisely.

Grade 8:

▶Instruct students to change the paragraph's

voice (active/passive) or mood (conditional/

subjunctive). Examine how this affects the text.

Page T4

January–February 2015

Frozen: Science

Explore Science

Interpreting A Frozen Food Web

Developing a Larger Antarctic Food Web

1. D

isplay the diagram on page 7 of the projectable

1. P

rior to conducting this activity, write the following

edition. Invite a volunteer to read the introductory text

aloud. Then examine the organisms in the diagram

with the class. Instruct students to identify each as a

plant or animal, and as a producer or consumer.

on slips of paper: orca, petrel, Weddel seal/fur seal,

amphipods, pteropod, crabeater seal, ctenophores,

fish, squid, leopard seals, krill, copepods, penguins,

baleen whales, jellyfish, phytoplankton, salps. You will

also need to: cover a bulletin board with blue paper;

get a stapler, index cards, and markers; and download

the Antarctic summer environment interactive at:

http://polardiscovery.whoi.edu/antarctica/ecosystem.html.

2. R

emind the class that food webs consist of overlapping

food chains. Give students a moment to examine the

food web in the diagram. How many food chains

does it contain? (6) Invite volunteers to trace the

path of each.

2. E

xplain that the food web in the article includes just

a few of the organisms that live in, on, and around

Antarctic icebergs. Display the interactive. Click a few

dots. Introduce students to more Antarctic organisms.

3. C

ompare and contrast the food chains. Guide

students to recognize that they all have the same

beginning. (diatoms, a single-cell plant) Point out

that they are different lengths. (3-5 steps) Explore

how they flow together to create the food web.

3. G

ive each student or pair of students a slip of paper.

Tell them to conduct research to find out what their

organism eats and what eats it. Suggest that they begin

with data on the interactive. Then have students draw

and identify their organisms on the cards.

Understanding Energy Transfer

1. D

isplay page 7 of the projectable edition. Point

out that this type of diagram is called a "food web"

because it shows who eats what in an ecosystem.

What else does it show? (the transfer of energy)

4. I nstruct students to staple their cards to the bulletin

board. Then have them draw lines connecting their

organism to those that it eats and those that eat it.

Once all lines are drawn, examine this area's food web.

2. T

o illustrate what this means, draw a large triangle

shaped like the one below on the board:

Extend Science

Seasonal Changes in a Food Web

1. P

rior to conducting this activity, download the

Antarctic summer and winter environment

interactives at: http://polardiscovery.whoi.edu/antarctica/

ecosystem.html.

3. I nform students that a diagram showing energy

transfer in a food web is shaped like this. Why? (A

food web begins with a set amount of energy. Each

time a new organism uses energy, the total amount

of available energy decreases.)

2. I nvite students to name plants and animals they

see during different times of the year. Make a list.

Then display the summer and winter interactives

for students to compare. (Jellyfish, phytoplankton,

and salps only appear in summer. Juvenile krill only

appear in winter.) Ask: Based on this information,

which season is depicted in the food web diagram on

page 7 of your magazine? (summer) How do you know?

(Diatoms (phytoplankton) only appear in summer.)

4. E

xplain that an energy transfer diagram is also

divided into levels. Producers, who use energy

from sunlight to make their own food, are located

at the bottom. They're followed by primary

consumers, secondary consumers, etc. The final

consumer at top gets the least amount of energy.

5. I nvite volunteers to draw energy transfer diagrams

for each food chain in the food web and a

cumulative diagram for the entire food web.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer 3. G

uide students to recognize that seasonal variations

affect food webs—even in Antarctica.

Page T5

January–February 2015

Frozen!

Name:

Activity Master

Examining Text Structure

Explain

Explain

© 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

Analyze

Analyze

Identify

Identify

Use this graphic organizer to identify, analyze, and explain key parts

of the text.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T6

January–February 2015

Frozen!

Assessment

Name:

Read each question. Fill in the circle next to the correct answer or write your response on the lines.

Which of these is a producer in an iceberg food web?

krill

diatom

petrel

2. How are the food chains in a food web organized?

They are parallel.

They are perpendicular.

They overlap.

3. Where do icebergs get the nutrients that plants need to grow?

from water

from land

from air

4. Where does the energy in an iceberg food web come from?

the ice

the plants

the sun

5. How are an iceberg food web and a desert food web the same? How are they different?

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T7

January–February 2015

© 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

1. Frozen!

Name: Answer Key

Activity Master

Examining Text Structure

Use this graphic organizer to identify, analyze, and explain key parts

of the text.

Identify

Identify

Grade 6: Students should choose one sentence, paragraph, or section of the article.

Grade 7: Students should identify the overall text structure.

Grade 8: Students should identify one paragraph.

Grade 7: Students should analyze how the major sections contribute to the whole.

Grade 8: Students should analyze the role of key sentences in that paragraph.

Grade 6: Students should explain how the selected sentence, paragraph, or section contributes

to the development of the ideas.

Grade 7: Students should explain how the major sections contribute to the development of the

ideas.

Grade 8: Students should explain the role of key sentences in developing and refining a key

concept.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T6A

T6

January–February 2015

© 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

Explain

Explain

Analyze

Analyze

Grade 6: Students should analyze how the selected sentence, paragraph, or section fits into the

overall structure of the text.

Frozen!

Assessment

Name:

Answer Key

Read each question. Fill in the circle next to the correct answer or write your response on the lines.

Which of these is a producer in an iceberg food web?

krill

diatom

petrel

2. How are the food chains in a food web organized?

They are parallel.

They are perpendicular.

They overlap.

3. Where do icebergs get the nutrients that plants need to grow?

from water

from land

from air

4. Where does the energy in an iceberg food web come from?

the ice

the plants

the sun

5. How are an iceberg food web and a desert food web the same? How are they different?

Possible responses: Both begin with the sun, which provides energy for producers to

make their own food through photosynthesis. Both contain several types and levels of

consumers in overlapping food chains. Energy is transferred from one organism to

another in both. Due to their locations, they contain different organisms.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T7A

January–February 2015

© 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

1. Spinosaurus: Overview

Summary

Materials Needed

• Spinosaurus was the biggest carnivore to ever live on

Earth. Inspired by a mysterious fossil, paleontologist Nizar

Ibrahim set out on a quest that ended with a surprising

revelation: Spinosaurus lived mostly in the water.

• a dictionary

• strips

of paper

• paper bags

• "The

Search for Spinosaurus" poster

Curriculum in This Article

• National Geographic's "Building the Beast" interactive

at: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2014/10/

Common Core State Standards

spinosaurus/beast-graphic

• Trace/delineate and evaluate the argument and

specific claims in a text. (RI.6/7/8.8)

• With some guidance and support from peers and

adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed

by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a

new approach, (focusing on how well purpose and

audience have been addressed). (W.6/7/8.5)

• Use the relationship between particular words to

better understand each of the words. (L.6/7/8.5.b)

• National Geographic's "Pieces of the Puzzle" interactive

at: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2014/10/

spinosaurus/puzzle-graphic

• National Geographic's "'River Monster'—50Foot Spinosaurus" video at: http://video.

nationalgeographic.com/video/magazine/140911-ngmsuperjaws?source=relatedvideo

• National Geographic's "A Behind-the-Scenes Look

at Assembling Spinosaurus" video at: http://video.

Next Generation Science Standards

nationalgeographic.com/video/proof/a-behind-the-sceneslook-at-assembling-spinosaurus?source=relatedvideo

• Performance Expectation: Construct an explanation

that predicts patterns of interactions among

organisms across multiple ecosystems. (MS-LS2-2)

• National Geographic's "Bigger Than T. rex" video at:

• S cience and Engineering Practice: Constructing

Explanations and Designing Solutions

• National Geographic audio critique at: http://ngm.

• Disciplinary Core Idea: Interdependent

Relationships in an Ecosystem—Similarly, predatory

interactions may reduce the number of organisms or

eliminate whole populations of organisms. Mutually

beneficial interactions, in contrast, may become

so interdependent that each organism requires the

other for survival. Although the species involved

in these competitive, predatory, and mutually

beneficial interactions vary across ecosystems, the

patterns of interactions of organisms with their

environments, both living and nonliving, are shared.

http://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/news/140911spinosaurus-discovery-vin?source=relatedvideo

nationalgeographic.com/2007/12/bizarre-dinosaurs/holtzdinosaur-photography

Additional Resource

• Watch

Nizar Ibrahim describe the search for

Spinosaurus:

▶http://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/ng-live/

ibrahim-dinosaur-lecture-nglive?source=relatedvideo

• Crosscutting Concept: Patterns

To access the projectable edition of this

article, go to the Teacher tab for this

magazine at ngexplorer.cengage.com.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T8

January–February 2015

Spinosaurus: Background

Fast Facts

• Spinosaurus aegyptiacus was first discovered by German

paleontologist Ernst Stromer. Between 1910 and 1914,

Stromer and his team uncovered two partial skeletons

while searching for fossils in the Egyptian Sahara. The

collection, housed in a Munich museum during World

War II, was destroyed during an Allied raid in April

1944.

• In 2008, paleontologist Nizar Ibrahim purchased some

strange fossils from a man in Egypt. The next year, after

viewing partial dinosaur skeletons in Italy, Ibrahim

began to suspect that one of his own strange fossils was

part of the same species, Spinosaurus.

• Spinosaurus

was more than 15.2 meters long, 6 meters

high, and weighed about 5.4 tonnes. It was the largest

carnivore to ever live on Earth.

• Had

they lived at the same time, Spinosaurus would

have dwarfed Tyrannosaurus rex. The largest T. rex

was just 12.3 meters from head to tail.

• Spinosaurus was named for the two-meter sail on its

spine. The name, Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, translates to

"spine lizard of Egypt."

• Ibrahim set out on a search that led him to sandstone

cliffs in the Sahara. There, he found additional remains

of this dinosaur that lived during the middle of the

Cretaceous period, 100 to 94 million years ago.

• To uncover Spinosaurus' secrets, Ibrahim used a CTscanner to digitally reconstruct the dinosaur. His results

yielded several notable characteristics:

▶It had a long neck and an extended trunk.

▶It had several characteristics similar to a

crocodile: a long, narrow head, nostrils halfway

up its skull, and cone-shape teeth.

▶It had dense bones. The sea cow has similar

bones, which it uses control its buoyancy in

water.

▶It had flat back feet that looked like paddles, or

webbed feet.

▶Its tail vertebrae looked a lot like the vertebrae in

a flexible fish's tail.

• After studying the dinosaur's body and comparing it

to animals living today, Ibrahim came to a conclusion:

Spinosaurus was adapted for life in the water. It is the

first known semi-aquatic dinosaur.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T9

January–February 2015

Spinosaurus: Prepare to Read

Activate Prior Knowledge

Vocabulary

1. Instruct students to think about a time they lost

1. Display page 14 of the projectable edition and zoom

2. Now tell them to imagine that they weren't the one

2. Invite a volunteer to highlight ecosystem each time

Setting the Scene for a Difficult Search

Tackling Higher Level Scientific Terms

something really important. How did they search for

it? Where did they search for it? Did they search more

because it was really important?

who lost it. Would this make it harder to find? Why?

3. Finally, present students with this scenario and

invite them to respond: What if the thing you were

searching for was a dinosaur fossil. You knew it was

buried somewhere in the desert, but you had no idea

where. And you only knew of one other person who had

ever found any part of this fossil before. However, you

couldn't ask that person for advice because he found the

bones over a hundred years ago. What would you do?

in on the Wordwise words. Give students a moment

to examine the terms. How are three of the four terms

connected? (They contain the word ecosystem.)

it appears. Point out that in one case it's a Wordwise

word. In the other two, it's part of the definition.

3. Explain to students that as they start to encounter

higher level scientific terms, this practice will become

more common. Definitions may contain words they

don't understand. Ask: What should you do if you ever

run into this problem? (Look up the unknown words.)

4. Invite a volunteer to read aloud the word ecosystem

and its definition. Discuss the definition as a class.

Then invite another volunteer to read aloud the

definition for apex predator. Identify apex as a

potentially confusing word, and have a volunteer

look it up in a dictionary. Discuss how hearing the

definition helped them understand the term apex

predator and its connection to ecosystem.

5. Repeat this process with the remaining terms.

Encourage students to make their own connections

between fossil record and ecosystem. Then challenge

students to explain why each of these terms might be

important in an article about a dinosaur.

ELL Connection

Vocabulary Matching Game

1. Display the Wordwise words on page 14 of the

projectable edition. Invite volunteers to read aloud the

words and their definitions. Discuss each.

2. Then divide the class into small groups. Give each

group eight strips of paper and a paper bag. Instruct

students to write one Wordwise word or one definition

on each strip and to put the papers in their bags.

3. State one word or definition. Instruct groups to each

pull a paper from their bags. If it's the definition for

the word or the word, they keep the strip. If it's not,

the strip goes back in the bag. Continue until one

group has removed all papers from its bag.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T10

January–February 2015

Spinosaurus: Language Arts

Explore Reading

Explore Writing

1. Ask students what they do when they want to prove

1. A

s a class, review the poster "The Search for

Investigating Claims

Crafting a Journal

that something is true. (They find evidence.) Explain

that writers and scientists do the same thing. When

they make a claim, they supply reasons that tell why

something happened and evidence that shows how.

2. Display pages 8-9 of the projectable edition. Invite a

volunteer to read aloud the headline and deck, and

encourage students to comment on what they see.

3. Point out that the writer makes two specific claims

on this page. (Spinosaurus was the world's oddest

dinosaur. It ruled the river of giants.) Tell students

that they will discover the reasons and evidence she

used to support these claims as they read the article.

Discuss why it's important for readers to evaluate this

information. Introduce the grade-level objective below

to explore how this can be done.

4. Give each student a copy of the

Activity Master. Have them read

the article on their own. As they

do, direct students to use the

graphic organizer to trace and

evaluate the reasons and evidence

that the writer uses to support

each claim. Challenge them to

identify one other claim the writer

makes and evaluate it as well.

Spinosaurus." Discuss the chain of events that led to

Ibrahim's discovery.

2. I nstruct students to imagine that they are Nizar

Ibrahim, the paleontologist who tracked down

Spinosaurus. Challenge them to create a journal,

written from Ibrahim's perspective. Tell students to

include an entry corresponding to each event on the

poster as well as four other important moments during

his journey. Suggest that they review the article before

writing to ensure that they cover events in the proper

order and include relevant and interesting facts.

3. G

ive students time to write a first draft. Then have

them switch with a partner. Instruct students to review

the entries and make helpful suggestions regarding

content, grammar, punctuation, spelling, and style.

Instruct students to revise their work. Then invite

them to share their journals—and their insights on

Ibrahim's work—in small groups.

Explore Language

Examining Relationships Between Words

Activity Master,

page T13

5. When students are finished, instruct them to share

and compare their results with a partner.

illustrating various types of word relationships:

Grade 6:

▶Instruct students to distinguish claims that are

supported by reasons and evidence from claims

that are not.

Grade 7:

▶Direct students to assess whether the reasoning is

sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient to

support the claims.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer the word oddest, insert a note above it, and write

strangest on the note. Ask: How are these words related?

(synonyms) Explain that synonyms are a type of word

relationship. Recognizing these relationships helps

readers understand both words better.

2. U

se words from the article to create analogies

Common Core Grade-Level Differentiation

Grade 8:

▶Challenge students to scan the article to ensure

that no irrelevant evidence is introduced.

1. D

isplay pages 8-9 of the projectable edition. Highlight

▶dig : find :: bury : hide (cause/effect)

▶sand : desert :: water : river (part/whole)

▶Sahara : desert :: rib : bone (item/category)

▶puzzle : riddle :: rock : stone (synonym)

▶ancient : new :: dangerous : safe (antonyms)

3. H

ave students create article-based analogies of their

own. Collect the analogies. Write them on the board,

deleting one word in each relationship. Challenge

students to fill in the missing words. Discuss how the

relationship helped them understand each word.

Page T11

January–February 2015

Spinosaurus!: Science

Explore Science

Coexistence in a Prehistoric Ecosystem

Using Patterns to Decipher Spinosaurus

1. Prior to conducting this activity, download the

1. Instruct students to review the section "Building the

Beast" on page 14 of their magazines. Challenge them

to outline the process Ibrahim used to build and then

interpret the Spinosaurus skeleton.

following National Geographic assets. Create five

Investigation Stations with one item at each station.

▶"Building the Beast" interactive at: http://ngm.

nationalgeographic.com/2014/10/spinosaurus/beastgraphic

▶"Pieces of the Puzzle" interactive at: http://ngm.

nationalgeographic.com/2014/10/spinosaurus/puzzlegraphic

▶"'River Monster'—50-Foot Spinosaurus" video

at: http://video.nationalgeographic.com/video/

magazine/140911-ngm-superjaws?source=relatedvideo

▶"A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Assembling

Spinosaurus" video at: http://video.

nationalgeographic.com/video/proof/abehind-the-scenes-look-at-assemblingspinosaurus?source=relatedvideo

▶"Bigger Than T. rex" video at: http://video.

nationalgeographic.com/video/news/140911spinosaurus-discovery-vin?source=relatedvideo

2. Invite students to share and compare their lists.

Challenge them to identify the various ways that

Ibrahim relied on patterns to solve the Spinosaurus

puzzle. (He used patterns to make comparisons with

sketches, photos, and bones of related dinosaurs. He

use anatomical patterns to reconstruct the dinosaur.

He used patterns in the anatomy and behavior of

modern-day animals to interpret what the dinosaur

looked like, how it acted, and where it lived.)

Extend Science

Rewriting Dinosaur History

1. Prior to conducting this activity, download the

National Geographic audio critique at: http://ngm.

2. Display page 10 of the projectable edition. Zoom in on

the last paragraph of the introduction and highlight

the last sentence: How could so many predators coexist

in one ecosystem?

3. Explain that the German scientist who discovered

Spinosaurus bones 100 years ago was the first to pose

this question. When Nizar Ibrahim began digging into

Spinosaurus, this was one of the questions he hoped

to answer. As he began investigating the dinosaur, he

formed a hypothesis—Spinosaurus mostly lived in the

water. Ibrahim needed evidence to prove this.

nationalgeographic.com/2007/12/bizarre-dinosaurs/holtzdinosaur-photography.

2. Display two or three samples of the audio critique

for students. Discuss how ideas about dinosaurs have

changed over the years. Then divide the class into

small groups. Challenge groups to use what they've

learned to write their own audio critiques about

Spinosaurus.

4. Remind students that scientific research follows a

process. Scientists identify a question, propose an

answer; conduct research to find evidence supporting

the claim; and use the evidence to show why the

answer is correct.

5. Divide the class into five groups. Instruct groups

to review the article to collect as much evidence

as possible. Then have groups visit each station for

additional evidence that explains how the predators

could coexist. Encourage groups to use their findings

to craft a report that supports Ibrahim's conclusion.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T12

January–February 2015

Spinosaurus!

Name:

Activity Master

Investigating a Writer's Claims

Identify and evaluate two claims the writer makes about Spinosaurus.

Identify and evaluate another claim that you find as you read the text.

Key PSpinosaurus

oint: The bone Ibrahim Claim:

wasled theNizar worldʼs

on an oddest

amazing journey. dinosaur.

Reasons and Evidence: Identify Reasons

Identify Evidence

Claim:

Spinosaurus

ruled the

river

Key Point: He discovered one of the oddest of

dinosaurs giants. that ever lived. Reasons and Evidence: Identify

Reasons

Evaluate Claim

Identify Evidence

Evaluate Claim

Identify Evidence

Evaluate Claim

Claim:

Key Point: Reasons and Evidence: Identify

Reasons

National Geographic Extreme Explorer

Page T13

January–February 2015

© 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

Spinosaurus!

Name:

Assessment

Read each question. Fill in the circle next to the correct answer.

Why did the ancient Sahara ecosystem puzzle scientists?

The Sahara was full of rivers and swamps.

There were too many carnivores.

The animals were all extremely large.

2. Why are there typically one or two apex predators in an ecosystem?

There isn't enough food to support more.

Only the biggest animals can be apex predators.

Apex predators always rule the land.

3. At what point did Nizar Ibrahim realize that Spinosaurus lived mostly in the water?

when he found the bones

when he saw the photos and sketches

when he saw the finished skeleton

4. Which of these clues helped Ibrahim reach this conclusion?

similarities between Spinosaurus and animals living today

Spinosaurus' size and the structure of its sail

streaks in the original fossil Ibrahim found

5. © 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

1. What did Ibrahim's conclusion prove?

Spinosaurus was a predator.

Spinosaurus had its own niche.

Spinosaurus lived in the Sahara.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T14

January–February 2015

Spinosaurus!

Name: Answer Key

Activity Master

Investigating a Writer's Claims

Identify and evaluate two claims the writer makes about Spinosaurus.

Identify and evaluate another claim that you find as you read the text.

Key PSpinosaurus

oint: The bone Ibrahim Claim:

wasled theNizar worldʼs

on an oddest

amazing journey. dinosaur.

Reasons and Evidence: Identify Reasons

Possible Response: Spinosaurus

looked different from any

dinosaur he'd ever seen.

Identify Evidence

Possible Response: It was

bigger than a T. rex, had a

head like a crocodile, bones

like a sea cow, a tail like that

of a flexible fish, a giant sail,

and back feet that reminded

Ibrahim of paddles.

Claim:

Spinosaurus

ruled the

river

Key Point: He discovered one of the of

giants

oddest dinosaurs that ever lived. Reasons and Evidence: Identify

Reasons

Identify Evidence

Possible Response:

Spinosaurus was a huge,

dangerous predator that lived

mostly in the water.

Possible Response:

Spinosaurus was 15 m long,

bigger than T. rex. With

nostrils halfway up its skull and

long, sharp, cone-shape teeth,

it could easily hide in the

water and catch prey. It was

the apex predator with its own

niche in a river ecosystem.

Evaluate Claim

Answers will vary. Students

should cite grade-level criteria

when evaluating claims.

Evaluate Claim

Answers will vary. Students

should cite grade-level

criteria when evaluating

claims.

Claim:

Answers

will vary.

Key Point: Reasons and Evidence: Identify

Reasons

Answers will vary.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer

Identify Evidence

Answers will vary.

Page T13A

Evaluate Claim

Answers will vary. Students

should cite grade-level

criteria when evaluating

claims.

January–February 2015

© 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

Spinosaurus!

Name:

Assessment

Read each question. Fill in the circle next to the correct answer.

Why did the ancient Sahara ecosystem puzzle scientists?

The Sahara was full of rivers and swamps.

There were too many carnivores.

The animals were all extremely large.

2. Why are there typically only one or two apex predators in an ecosystem?

There isn't enough food to support more.

Only the biggest animals can be apex predators.

Apex predators always rule the land.

3. At what point did Nizar Ibrahim realize that Spinosaurus mostly lived in the water?

when he found the bones

when he saw the photos and sketches

when he saw the finished skeleton

4. Which of these clues helped Ibrahim reach this conclusion?

similarities between Spinosaurus and animals living today

Spinosaurus' size and the structure of its sail

streaks in the original fossil Ibrahim found

5. © 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

1. What did Ibrahim's conclusion prove?

Spinosaurus was a predator.

Spinosaurus had its own niche.

Spinosaurus lived in the Sahara.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T14A

January–February 2015

Call of the Wildflowers: Overview

Summary

Materials Needed

• For plants to reproduce, pollination must occur. For

some plants, this means attracting a bat. Biologist

Ralph Simon has a theory about how this happens.

He says some flowers use sound to attract bats.

• a dictionary

• index cards

• scissors

• Ralph Simon's video "Bats and Flowers" at: http://www.

Curriculum in This Article

rsimon.de/www.rsimon.de/Movies.html

Common Core State Standards

• Integrate information presented in different media

or formats as well as in words to develop a coherent

understanding of a topic or issue. (RI.6.7)

• the National Geographic "Call of the Bloom" photo

gallery at: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2014/03/

bat-echo/tuttle-photography#/04-blue-mahoe-pollenladen-bat-670.jpg

• C ompare and contrast a text to an audio, video,

or multimedia version of the text, analyzing each

medium’s portrayal of the subject. (RI.7.7)

• National

Geographic interactive "Form Feeds Function"

at: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2014/03/bat-echo/

• Evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of using

different mediums to present a particular topic or

idea. (RI.8.7)

• art supplies including construction paper, markers,

scissors, and pipe cleaners

• Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a

topic and convey ideas, concepts, and information

through the selection, organization, and analysis of

relevant content. (W.6/7/8.2)

• National

Geographic video "Untamed Americas: TubeLipped Nectar Bat" at: http://channel.nationalgeographic.

plant-interactive

• "Flower Power" poster

com/channel/untamed-americas/videos/tube-lipped-nectarbat/?source=searchvideo

• Ensure that pronouns are in the proper case. (L.6.1.a)

• Explain the function of phrases and clauses. (L.7.1.a)

Additional Resources

• E xplain the function of verbals. (L.8.1.a)

•R

ead more about Ralph Simon's theory:

▶http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2014/03/bat-echo/

mcgrath-text

Next Generation Science Standards

• Performance Expectation: Use argument based

on empirical evidence and scientific reasoning

to support an explanation for how characteristic

animal behaviors and specialized plant structures

affect the probability of successful reproduction of

animals and plants respectively. (MS-LS1-4)

• S cience and Engineering Practice: Engaging in

Argument from Evidence

• Disciplinary Core Idea: Growth and Development

of Organisms—Plants reproduce in a variety of

ways, sometimes depending on animal behavior and

specialized features for reproduction.

• Crosscutting Concept: Cause and Effect

National Geographic Extreme Explorer ▶ www.rsimon.de

• Learn more about Merlin Tuttle's work with bats:

▶http://news.nationalgeographic.com/

news/2014/02/140215-merlin-tuttle-smithsonian-batconservation-international-viruses-science-animals/

▶http://www.merlintuttle.com

To access the projectable edition of this

article, go to the Teacher tab for this

magazine at ngexplorer.cengage.com.

To access the free whiteboard lesson for

this article, go to the Teacher tab for this

magazine at ngexplorer.cengage.com.

Page T15

January–February 2015

Call of the Wildflowers: Background

Fast Facts

• Pollination is the process that leads to the creation of

new seeds. For pollination to occur, pollen must move

from the male parts of a flower to the female parts.

• The stamen is the male part of a flower. Its parts

include:

•F

or seeds to grow, pollen must be transferred between

flowers of the same species.

•M

ore than 80% of flowering plants depend on animals

for pollination.

•B

ats are important pollinators in desert and tropical

climates, particularly in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the

Pacific Islands.

▶anther: the part that produces pollen

▶filament: the long, thin stalk that holds up the

anther

• The entire female reproductive part is called the carpel.

The carpel contains these main parts:

▶stigma: the sticky top of the stigma where pollen

collects

•A

tube-lipped nectar bat has the longest tongue of any

mammal. It's one-and-a-half times the length of its

body. That makes it the only animal that can reach the

nectar of a particular flower in Ecuador.

▶style: the tissue that connects the stigma to the

ovary

▶ovary: the bottom of the carpel where seeds grow

into plants

• Some plants are self-pollinating. Pollen from an anther

can pollinate the stigma on the same plant. Other plants

are cross-pollinating. Wind, water, or animals must

transfer pollen from one plant to another. Animals that

do this are called pollinators.

• Animals don't transfer pollen on purpose. Most often,

pollination is a by-product that occurs when animals

go to flowers for food. To get to a flower's nectar, the

animal rubs against the stamen. Pollen on the anther

sticks to the animal's body. When the animal moves

on to the next flower, it transfers that pollen to the new

flower's stigma.

• While food is a great lure, flowers have developed

specific characteristics over time to ensure that they

attract the right pollinators. For example, flowers that

rely on butterflies often have bright red or purple

flowers. Those that need flies often have a putrid smell.

• Bats rely on echolocation to find their way. Biologist

Ralph Simon studies the structures of flowers that

depend on bats for pollination. He's found that these

flowers have parts that affect sound, such as shapes that

reflect sounds, that allow a bat to use echolocation to

find the flowers.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T16

January–February 2015

Call of the Wildflowers: Prepare to Read

Activate Prior Knowledge

Vocabulary

1. Read the combinations below to the class. After each,

1. Display the Wordwise words on page 23 of the article.

What Does It Mean to Communicate?

Organizing Pollination Words

take a class vote to see if students think these two

organisms ever communicate with one another.

▶a person and a dog

▶a skunk and a snake

▶a mother and baby cheetah

2. After the final vote, tell students that communication

takes place in all three combinations. However, how

and why these organisms communicate can be very

different.

3. Provide examples: People pat dogs to show their

affection. Dogs wag their tails in appreciation. Skunks

send a strong smelling message when hissing snakes

attack, and mother cheetahs demonstrate survival

skills for their babies.

4. Guide students to understand that there are many

2. Challenge students to use their cards to illustrate

a meaningful connection between two or more

vocabulary words. For example, they could put the

words in sequence. (pollen + pollinator = pollination)

Or they could show the relationship between words.

(stamen → anther)

3. Invite volunteers to share their combinations.

Encourage them to make as many logical connections

as possible.

ELL Connection

different types of communication, and each type of

communication has a purpose.

5. Then inform the class that the article they are about

Review the definitions with the class. Then give each

student seven index cards. Have them write each

vocabulary word on a separate index card. Instruct

them to cut the remaining card into thirds and write a

plus sign, an equal sign, and an arrow on the pieces.

Examining Connections Among Words

1. Display the Wordwise words on page 23 of the

to read is about a biologist named Ralph Simon. He

says that some flowers use sound to communicate with

bats. Encourage students to share their thoughts on

Simon's theory.

projectable edition. Highlight the words pollen,

pollinate, and pollinator.

2. Challenge students to explain how these words are

alike and different. Guide them to recognize that all

three words have the same root word: pollen. Review

the definition of pollen with the class.

3. Point out that the other two words end with the

suffixes -ate and -or. Invite volunteers to look these

suffixes up in a dictionary. Review the meaning of

each. (The verb suffix -ate means "to act on." The noun

suffix -or means "one who does a thing.") Read the

definitions and review how the suffix determined the

meaning of each.

4. Examine the three remaining words. They share a

different connection. What is it? (They are parts of a

flower.) Explore this connection and the link between

the plant parts and the other vocabulary words.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T17

January–February 2015

Call of the Wildflowers: Language Arts

Explore Reading

Explore Writing

1. P

rior to reading the article, download Ralph Simon's

1. P

oint out to students that this article brings up three

Learning Through a Multi-Media Approach

Write an Explanatory Essay

video "Bats and Flowers" at: http://www.rsimon.de/www.

rsimon.de/Movies.html. Also download the National

Geographic "Call of the Bloom" photo gallery at: http://

ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2014/03/bat-echo/tuttlephotography#/04-blue-mahoe-pollen-laden-bat-670.jpg.

2. D

isplay pages 17-18 of the projectable edition.

Encourage students to examine the photo and describe

what they see. Then invite a volunteer to read aloud

the headline and deck. Brainstorm ideas with students

about what they expect to learn as they read the article.

3. A

ssign each student a partner. Instruct pairs to read

the article. As they do, tell them to take detailed notes

outlining what they learn and citing the source of this

information, such as the text, an image, a caption, a

diagram, etc.

4. A

fter students finish reading the article, display the

video and photo gallery. Instruct students to record

anything new that they learn from these two sources.

Then challenge them to examine their notes from

the perspective outlined in the grade-level guidelines

below. When all pairs are finished, rejoin as a class.

Encourage students to share what they learned.

Common Core Grade-Level Differentiation

Grade 6:

▶Give each pair an index card. Challenge them to

use the card in a creative way to show what they

learned about the topic. Require them to integrate

information from all three sources.

Grade 7:

▶Instruct students identify three key points they

learned about the topic. Challenge them to analyze

how this information was conveyed in the article,

video, and photos. Compare and contrast the

effectiveness of each approach.

Grade 8:

▶Encourage students to evaluate the advantages and

disadvantages of using text, photos, diagrams, and

videos to present evidence that flowers call bats.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer key questions: How do plants call bats? Why do plants

call bats? and Why do bats come when a plant calls?

Inform students that the best way to answer each of

these questions is through an explanatory text.

2. I nform students that an explanatory text denotes

authority on a topic. Because of that, it commands a

formal writing style. As in other essays, an explanatory

essay begins with a topic sentence that introduces

the main idea. That idea is developed through facts,

details, definitions, quotes, examples, visuals, etc.

Transitional words and phrases connect the ideas and

help the text flow smoothly. A concluding statement

supporting the explanation ties everything together.

3. P

air students. Give each

student a copy of the

Activity Master. Have pairs

select a question to address

and then review the article

to find and record relevant

information. Instruct

Activity Master,

students to use the Activity

page T20

Master as a guide to write a short

explanatory essay addressing their topic. Encourage

each pair to include a visual in their report.

Explore Language

Ensuring Proper Grammar Usage

1. R

eview the proper grade-level objective with students:

▶Grade 6: Pronouns—When do you use the

subjunctive, objective, or possessive case?

▶Grade 7: Phrases and clauses—What's the

function of each in specific sentences?

▶Grade 8: Verbals—What are gerunds, participles,

and infinitives and what do they do?

2. D

ivide the class into small groups. Instruct students

to use information from the article to write a "How To

Connect" guide for a plant or a bat. Challenge them to

include at least three examples of the grammar topic

they just reviewed.

Page T18

January–February 2015

Call of the Wildflowers: Science

Explore Science

Utilizing Evidence and Scientific Reasoning

Calling All Bats!

1. Prior to conducting this activity, download the

1. To complete this activity, gather art supplies including

construction paper, markers, scissors, and pipe

cleaners.

National Geographic interactive "Form Feeds

Function" at: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.

com/2014/03/bat-echo/plant-interactive.

2. Point out to the class that if a flower needs a particular

2. Display pages 16-17 of the article. Read the deck

aloud, and highlight the words "find evidence." Then

display page 18. Zoom in on the second paragraph

of the introduction. Highlight the words "claim" and

"argues." Ask: When you put all of these words together,

what do they tell you?

3. Guide students to recognize that the article explains

a new theory. Biologist Ralph Simon has gathered

evidence through experiments and observations to

prove his theory. He then combined this evidence

with scientific reasoning to support his argument that

plants use sound to attract bats.

4. Challenge students to make their own scientific

arguments using information in the article. Instruct

students to review the article to collect evidence that

supports Simon's theory. Then display the "Form

Feeds Function" interactive. Encourage students to

discuss and interpret the information on each screen

and record further evidence that supports Simon's

theory.

5. Divide the class into small groups. Instruct students

to pool their evidence and review it from a scientific

standpoint. Encourage groups to identify key facts and

details that support Simon's theory. Then rejoin as a

class. Challenge each group to determine whether or

not Simon has enough evidence to prove his theory

that plants call to bats.

kind of pollinator, it must do something to encourage

the animal to visit. Invite volunteers to describe how

they think the flower could do this.

3. Display the poster "Flower Power." Explain to students

that the poster tells about four ways flowers attract

bats. Examine each method in detail to identify the

most important factors of each component. (Sound:

curved leaves; Position: hangs out in the open; Shape:

deep, narrow flower; Smell: smells like garlic or has

musty or slightly rotten smell) Discuss reasons why

Ralph Simon's theory about sound is so important.

4. Instruct students to sit in small groups. Give each

group an assortment of supplies. Then challenge each

group member to create his or her own model of a

flower built to attract a bat. Encourage groups to share

ideas about how they could show each characteristic,

particularly smell. Allow students to study the images

in their magazines for examples.

5. When all models are finished, invite volunteers to

share their flowers with the class. Encourage them to

explain how their flower's design makes it attractive to

bats.

Extend Science

Bat Parts: Answering a Flower's Call

1. Prior to conducting this activity, download the

National Geographic video "Untamed Americas:

Tube-Lipped Nectar Bat" at: http://channel.

nationalgeographic.com/channel/untamed-americas/

videos/tube-lipped-nectar-bat/?source=searchvideo.

2. Display the video for the class. Based on the evidence

in the video, challenge students to construct an

argument that bats and plants have complimentary

parts that help each organism survive.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T19

January–February 2015

Call of the Wildflowers

Activity Master

Name:

Write an Explanatory Essay

Supporting Details

Page T20

Ideas for Visuals

January–February 2015

Words and Their Definitions

Use this graphic organizer to record important information from the article. Then on the back write

an explanatory essay that answers a question about plants, bats, and pollination.

Topic Sentence:

Important Facts

Concluding Statement:

National Geographic Extreme Explorer © 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

Call of the Wildflowers

Name:

Assessment

Read each question. Fill in the circle next to the correct answer or write your response on the lines.

How does Ralph Simon say some flowers call to bats?

They reflect sounds.

They make high-pitched sounds.

They follow sounds.

2. Which type of plant is best at calling bats?

one with red leaves

one with fuzzy leaves

one with curved leaves

3. How does calling bats help flowers?

It makes flowers produce pollen.

It turns the flower into a pollinator.

It leads to pollination.

4. Why would a bat want to answer this call?

It will lead the bat to food.

It will help the bat find a home.

It will keep the bat safe from predators.

5. © 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

1. Explain in four steps how a plant uses sound to call a bat.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T21

January–February 2015

Call of the Wildflowers

Activity Master

Name:

Write an Explanatory Essay

Answer Key

Use this graphic organizer to record important information from the article. Then on the back write

an explanatory essay that answers a question about plants, bats, and pollination.

Supporting Details

Wordwise words are likely choices,

but words may vary depending on

the question selected.

Words and Their Definitions

Students' responses will vary but should relate to the question they choose to address.

Topic Sentence:

Important Facts

Details will vary depending on the

question selected. However, all

details should come directly from the

article and should support the topic.

January–February 2015

Students may choose to use a photo

or diagram from the article, or they

may elect to use information from the

article to create a diagram of their

own.

Ideas for Visuals

Facts will vary depending on the

question selected. However, all facts

should come directly from the article

and should support the topic.

Concluding Statement:

Page T20

T20A

Concluding statements should reiterate the topic sentence and relate to the question answered in the essay.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer © 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

Call of the Wildflowers

Answer Key

Name:

Assessment

Read each question. Fill in the circle next to the correct answer or write your response on the lines.

How does Ralph Simon say some flowers call to bats?

They reflect sounds.

They make high-pitched sounds.

They follow sounds.

2. Which type of plant is best at calling bats?

one with red leaves

one with fuzzy leaves

one with curved leaves

3. How does calling bats help flowers?

It makes flowers produce pollen.

It turns the flower into a pollinator.

It leads to pollination.

4. Why would a bat want to answer this call?

It will lead the bat to food.

It will help the bat find a home.

It will keep the bat safe from predators.

5. Explain in four steps how a plant uses sound to call a bat.

Student responses should relate the information in the diagram "Calling Bats:" 1. A bat

makes high-pitched sounds as it flies. 2. The sounds hit a curved leaf. 3. The sounds echo

off the leaf. 4. The bat follows the echoes to the flower.

National Geographic Extreme Explorer Page T21A

January–February 2015

© 2015 National Geographic Learning. All rights reserved. Teachers may copy this page to distribute to their students.

1.