Gender and Reproductive Health Study

Policy Brief No. 6

Understanding of sexual harassment among Year 6 and Year 12 students in

Jakarta, West Java, West Nusa Tenggara and South Sulawesi

Iwu Dwisetyani Utomo, Peter McDonald, Terence Hull,

Ariane Utomo, and Anna Reimondos

Sexual harassment can be defined as unwelcome

behaviour of a sexual nature. It can take the form

of an unwelcome sexual advance, a request for

sexual favour, verbal or physical conduct or a

gesture of a sexual nature, or any other behaviour

of a sexual nature that might reasonably be

expected or be perceived to cause offence or

humiliation to another (UN 2005). Some examples

of specific behaviours that can be classified as

constituting sexual harassment include:

Verbal, making sexual comments about a person’s

clothing, anatomy or looks, asking personal

questions about social or sexual life, making sexual

comments or innuendo; Non-verbal, staring at

someone, following a person, making sexual

gestures with hands; Physical, touching the

person’s clothing, hair or body and hugging,

kissing, patting or stroking (UN na).

cases of sexual harassment. Adults who oversee

and work in educational settings have a duty to

provide safe environments that support and

promote children’s dignity and development (UN

2006b).

In this paper we examine the actions teachers and

students would take in response to sexual

harassment. The first part of the analysis

examines the responses of 521 teachers regarding

their understanding of sexual harassment, as

judged by whether they classify a series of

behaviours as constituting sexual harassment or

not as well as the actions they would take if a

student came to them with a report of sexual

harassment. The second part examines what

actions students would take in response to

unwanted physical touching, using data from 1,837

class 6 students and 6,555 class 12 students.

In recent years, the issue of sexual harassment of

children and adolescents has gained prominence

(Jones et al 2008). A large scale worldwide study

conducted by the United Nations found that

children are vulnerable to sexual and genderbased violence in educational settings (UN 2006a).

Although both males and females can be either

the victims or the offenders in cases of sexual

harassment, typically girls are particularly

vulnerable of being victims of unwanted sexual

behaviour from male classmates or teachers (UN

2006b).

Research from the US has highlighted the negative

effects that can result from sexual harassment in

school settings. For example, 40 percent of

students that were sexually harassed did not go to

school or skipped certain classes (American

Association of University Women, 1993; Fitzgerald,

1993). Victims of sexual harassment may also

suffer from negative psychosocial impacts such as,

depression, loss of appetite, disturbed sleep, low

self esteem, fear, and embarrassment (Gruber and

Fineran, 2007; Hand and Sanches, 2000; Lee et al.,

1996). Most worrying, perpetrators of sexual

harassment can be either students or adults.

Students report incidents of sexual harassment

more than teachers. Teachers and school

administrators might know about sexual

harassment by a male teacher of his female

students, but do not intervene (Wishnietsky,

1991).

Sexual harassment of children can have significant

negative effects on health and safety, enrolment

and educational achievement, as well as dignity,

self esteem and social relationships (Jones et al

2008). In more severe cases of sexual violence of

girls, unwanted pregnancies may be another

consequence.

While schools may in some cases be environments

in which sexual harassment occurs, they can also

be a place where children learn about sexual

harassment, and a place where they can

potentially seek help and support from teachers in

In Indonesia, media coverage of sexual harassment

in the school setting often reports severe

misconduct on the part of teachers including oral

sex, sexual intercourse and anal sex with students.

1

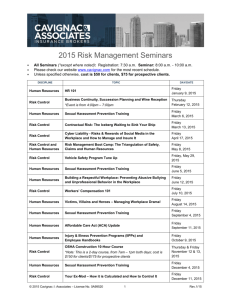

Figure 1. Percentage of teachers who classify a

behaviour as constituting sexual harassment, by sex

Cases that have been brought to court have

resulted in strong sanctions being applied to the

teacher (Kompas, 2008a and 2008b). But other

forms of sexual harassment by teachers upon

students such as touching, staring, using

inappropriate sexual words, and requesting sexual

favours so the student can pass exams are under

reported (Kompas, 2008c). Sexual violence may

often go unreported unless it is manifested in

extreme or serious behaviour because of the

culture of the teacher being seen as being in an

authority position.

Menjadi obyek pornografi

Diperkosa

Dipaksa memperlihatkan tubuh

tanpa busana

Dipaksa memegang bagian

kelamin orang lain

Dipegang-pegang bagian kelamin

Diraba/dicolek bagian tubuhnya

Dipandangi sehingga merasa tidak

nyaman

Dikatai-katai dengan ucapan tidak

senonoh

Dicemooh

Unlike studies of sexual harassment in the school

setting conducted in the United States, there are

no studies yet on this issue in Indonesia. Published

studies relate to sexual harassment specifically

rape in the conflict areas of Aceh, Papua and Timor

Leste as well as rape during the May 1998 riots

before the Soeharto resignation (Kamaruzzaman,

2003; Primariantari, 1999; Blackburn, 1999;

Wandita, 1998), but there are no studies of sexual

harassment in the school environment. This paper

seeks to understand sexual harassment and how

to deal with sexual harassment among teachers

and students in both general school and Islamic

religious schools in four provinces in Indonesia.

Perempuan

Laki-laki

0

20 40 60 80 100

Persentase (%)

Teachers in South Sulawesi stand out as being the

least likely to classify any behaviour as constituting

sexual harassment, compared to the teachers in

other provinces. Only 37 per cent of teachers in

Sulawesi classified unwelcome staring (Dipandangi

sehingga merasa tidak nyaman) as constituting

sexual harassment as compared to 60 per cent of

teachers in Jakarta, and 63 per cent of teachers in

West Java.

Large differences also emerged by school type.

Although there were no major differences in

classification of the less severe cases of sexual

harassment represented by the first three

behaviours, for the more serious behaviours,

teachers in religious schools were more likely to

classify that behaviour as sexual harassment

compared to teachers in non-religious schools.

These conclusions are also supported by further

logistic regression results.

Results for teachers

Definitions of sexual harassment

Teachers were presented with a list of nine

different behaviours ranging from being ridiculed

(verbal) to being raped (physical) and were asked

whether they believed each behaviour could be

classified as constituting sexual harassment. Table

1 shows the percentage of teachers who believed

a particular behaviour was a form of sexual

harassment, by selected characteristics of the

teachers, the province and the type of school

where they taught. Differences between teachers

according to the different demographic and school

characteristics were tested using chi-square tests.

Responses to sexual harassment

Teachers were also asked to identify what their

response would be if a student came to them to

report a case of sexual harassment. Seven

different responses were presented, with multiple

responses allowed. Nearly all teachers indicated

that they would try and calm the student down.

The next most frequent response was to discuss

the situation with fellow teachers (96%), and

report the incident to the parents of the child

(82%).

The key differences that emerged in teachers’

classification of sexual harassment were by sex,

province and whether or not the school was

religious. In general, female teachers were more

likely to classify a behaviour as constituting sexual

harassment.

Due to the high percentage of teachers that would

discuss the situation with fellow teachers, there

2

the incident to their teachers. These results are

also confirmed in the logistic regression.

were no significant differences of engaging in this

action by different teacher and school

characteristics, as shown in Table 2. However

there were some interesting province level

differences in the likelihood of reporting the

incident to the head of the school, or to the police.

In particular teachers in South Sulawesi were more

likely to indicate that they would report the

behaviour to the police, or to the head of the

school compared to teachers in the other

provinces. This result could be due to the fact that

teachers in South Sulawesi also appeared to have a

narrower definition of sexual harassment, which

included only the relatively serious cases of

physical harassment, as compared to teachers in

Jakarta who were more likely to consider verbal or

non-physical behaviours as constituting sexual

harassment

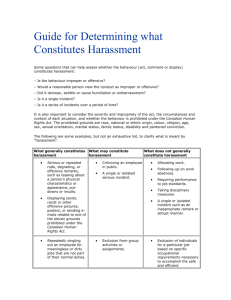

Student responses to sexual harassment

Students were also presented with seven possible

actions and were asked to indicate which ones

they would engage in if someone touched them in

an unwanted way.

Figure 2 shows the overall responses, comparing

class 6 students with students in class 12. In

general, class 6 students would be considerably

more likely to report such a behaviour to an

authority figure such as a parent, police, teacher,

or school head. In contrast class 12 students were

more likely to handle the matter themselves by

expressing anger and resisting the perpetrator or

by telling their friends about the incident.

The bivariate analyses for class 6 and class 12

students are shown in Tables 3 and 4 respectively.

For class 12 in particular, girls were much more

likely to report a case of unwanted touching or

take some other action. Boys were more likely to

say that they would do nothing (3% of girls vs. 22%

of boys).

In some cases, the behaviour of students appears

to show a significant shift from class 6 to class 12.

For example in class 6, it is students in Jakarta and

West Barat that are the most likely to report the

incident to their teachers but class 12 students in

these two provinces are the least likely to report

3

Table 1 Percentage of teachers who classify a behaviour as constituting sexual harassment, by sex

%

**

79

86

Dipegang

-pegang

bagian

kelamin

%

*

81

87

Dipaksa

memegang

bagian

kelamin orang

lain

%

*

81

86

Dipaksa

memperlihatkan

tubuh tanpa

busana

%

*

81

87

%

Dikatai-katai

dengan

ucapan tidak

senonoh

%

Jenis kelamin

Laki-laki

Perempuan

44

41

53

56

Dipandangi

sehingga

merasa tidak

nyaman

%

*

51

59

Propinsi

Jakarta

Jawa Barat

Nusa Tenggara Barat

Sulawesi

**

44

51

41

33

***

56

66

52

40

***

60

63

56

37

86

86

82

74

85

86

86

76

85

85

86

77

85

85

87

77

**

85

85

84

71

85

84

86

77

129

146

152

94

Jenis sekolah

Sekolah umum

Sekolah Agama Islam

**

48

39

55

55

55

56

***

75

89

***

77

91

***

78

89

***

78

90

***

76

88

***

78

88

247

274

Kategori sekolah

Sekolah Unggulan

Sekolah non unggulan

46

40

**

60

50

58

53

82

83

84

84

84

83

83

85

80

84

83

84

263

258

83

84

84

84

82

83

521

Dicemooh

Total

43

55

55

Note: * p<0.10, ** o<0.05, *** p<0.001 [Tested using a chi-square test]

Diraba/dicole

k bagian

tubuhnya

4

Diperkosa

Menjadi

obyek

pornografi

%

**

78

85

%

**

80

86

Total N

233

286

Table 2. Percentage of teachers that would take a particular action in response if a student reported a case of sexual harassment

Menenangkan

siswa/siswi

yang

bersangkutan

%

Marah

Melaporkan

pada

orangtua

Melaporkan

pada polisi

Mendiskusikan

dengan

sesama guru

%

*

78

84

%

%

47

53

97

95

Mendiskusikan/

melaporkan

pada kepala

sekolah

%

Mendiamkan

saja/tidak

melakukan

apa-apa

%

Total N

81

75

4

4

233

286

Jenis kelamin

Laki-laki

Perempuan

96

98

%

*

31

38

Propinsi

Jakarta

Jawa Barat

Nusa Tenggara Barat

Sulawesi

*

98

98

97

93

***

29

29

32

56

*

77

86

78

87

***

39

51

50

64

94

97

97

95

***

65

71

91

82

2

7

2

4

129

146

152

94

Jenis sekolah

Sekolah umum

Sekolah Agama Islam

97

97

37

32

82

81

48

52

95

96

80

75

3

5

247

274

50

51

95

96

75

79

*

5

2

263

258

50

96

77

4

521

Kategori sekolah

Sekolah Unggulan

Sekolah non unggulan

97

97

34

35

*

85

78

Total

97

35

82

Note: * p<0.10, ** o<0.05, *** p<0.001 [Tested using a chi-square test]

5

Figure 2. Response that would be taken if unwanted touching occurred, by class.

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

89

79

78

67

Class 6

59

44

38

34

21

Class 12

48

24

20

13 11

6

Table 3. Percentage of Class 6 students that would take a particular action in response if a student reported a case of sexual harassment

Marah

dan

melawan

Melaporkan

pada

orangtua

Melaporkan

pada polisi

Menceritakan

pada teman

Melaporkan

pada guru

Melaporkan

pada

kepala

sekolah

%

%

%

%

%

%

***

70

***

69

35

27

65

48

18

894

88

87

34

21

68

48

8

942

Propinsi

Jakarta

Jawa Barat

Nusa Tenggara Barat

Sulawesi

***

86

75

79

75

***

89

76

72

74

***

36

29

33

41

***

22

27

27

18

***

73

74

61

56

48

51

47

45

***

6

14

14

18

534

497

426

380

Jenis sekolah

Sekolah umum

Sekolah unggulan

***

82

76

80

76

**

37

31

*

22

26

**

70

63

47

49

**

11

15

1,063

774

Kategori sekolah

Sekolah Unggulan

Sekolah non unggulan

80

78

*

77

80

**

32

37

**

22

26

***

64

71

***

45

52

13

12

1,039

798

Total

79

78

34

24

67

48

13

1,837

Jenis kelamin

Laki-laki

Perempuan

***

Note: * p<0.10, ** o<0.05, *** p<0.001 [Tested using a chi-square test]

7

Mendiamkan

saja/tidak

melakukan

apa-apa

%

Total N

***

Table 4. Percentage of Class 12 students that would take a particular action in response if a student reported a case of sexual harassment

Marah

dan

melawan

Melaporkan

pada

orangtua

Melaporkan

pada polisi

Menceritakan

pada teman

Melaporkan

pada guru

Melaporkan

pada

kepala

sekolah

Jenis kelamin

Laki-laki

Perempuan

%

***

76

99

%

***

34

78

%

***

17

24

%

***

41

46

%

***

27

47

%

***

17

23

%

***

22

3

Propinsi

Jakarta

Jawa Barat

Nusa Tenggara Barat

Sulawesi

***

92

91

87

85

***

63

58

60

56

***

21

17

24

24

***

46

44

43

41

***

36

34

43

42

***

17

16

24

25

***

11

9

10

15

1,703

1,872

1,632

1,348

Jenis sekolah

Sekolah umum

Sekolah unggulan

***

88

91

***

58

61

21

21

44

44

**

38

40

20

21

***

13

8

3,862

2,693

Kategori sekolah

Sekolah Unggulan

Sekolah non unggulan

**

89

90

***

58

61

21

21

44

44

***

34

45

***

18

24

11

11

3,852

2,703

Total

89

59

21

44

38

20

11

6,555

Note: * p<0.10, ** o<0.05, *** p<0.001 [Tested using a chi-square test]

8

Mendiamkan

saja/tidak

melakukan

apa-apa

Total N

2,818

3,737

harassment in schools, identification of

the perpetrators whether they are

teachers or other adults working in the

school environment or other students

and whether the school authorities

tolerate sexual harassment behaviour.

School policies and programs need to be

developed and socialised regularly to

protect students and teachers from

sexual harassment.

Conclusion

Our survey results show that female

teachers were more likely to classify

behaviour as sexual harassment

comparing to male teachers. There are

some provincial differences where

teachers in South Sulawesi were the

least likely to classify any behaviour as

constituting sexual behaviour compared

to teachers in other provinces.

Teachers in religious schools were

significantly more likely to classify

behaviour such as being touched,

touching in the genital area, being forced

to touch another’s genitals, forced to be

naked, rape and being treated as a

sexual object as sexual harassment

compared to teachers in non-religious

schools. If students were harassed,

teachers would calm students, talk with

fellow teachers and report the incident

to the parents of the child.

References

American Association of University Women,

1993. Hostile hallways: the AAUW survey on

sexual harassment in America’s schools.

Washington DC.

Blackburn, S., 1999. Gender violence and the

Indonesian political transition. Asian Studies

Review, 23/4: 433-448.

Fitzherald, L.F., 1993. Sexual harassment:

violence against women in workplace.

American Psychologist, 48: 1070-1076.

Gruber, J.E. and Fineran, S. 2007. The impact

of Bullying and sexual harassment on middle

and high school girls. Violence Against

Women, 13/6: 627-643.

Among students, if harassed, girls were

more likely to report and take action

compared to boys. Year 6 students were

more likely to report harassment to

parents, police or teachers and school

principals while Year 12 students will

handle the matter themselves by

resisting the perpetrator or talking with

friends.

Hand, J. and Sanches, L. 2000. Badgering or

bantering? Gender differences in experience of

and reaction to, sexual harassment among

U.S. high school students. Gender & Society,

14: 718-746.

Jones, N., K. Moore, E. Villar-Marquez & E.

Broadbent. 2008. Painful lessons: The politics

of preventing sexual violence and bullying at

school. Working Paper 295 Overseas

Development Institute.

<http://dspace.cigilibrary.org/jspui/bitstream/12

3456789/25134/1/WP%20295%20%20Painful%20Lessons.pdf?1> Accessed 14

March 2012

This exploratory study has contributed to

knowledge of sexual harassment in the

school setting in Indonesia and has

revealed that students as young as Year

6 have a good understanding of sexual

harassment and who to report to in case

of harassment. Further study needs to

investigate the actual incidence of sexual

Kamaruzzaman, S., 2003. Mass rape in

situation of armed conflict (1989-1998) in

Naggroe Aceh Darussalam Province,

9

Indonesia. LLM thesis submitted to Faculty of

Law, University of Hongkong.

<http://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/UN_sys

tem_policies/(UNHCR)policy_on_harassment.p

df> Accessed 11 July 2012

Kompas, 2008a. Religious teachers had anal

sex with 26 Kindergarten students (Guru ngaji

sadomi 26 murid TK).

http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2008/04/10/0

3310597/guru.ngaji.sodomi.26.murid.tk.

Access 10 July, 2012.

United Nations. 2006a. World Report on

Violence Against Children. <

http://www.unicef.org/violencestudy/>

Accessed 11 July 2012

United Nations 2006b. United Nations

Secretary-General's Report on Violence

against Children

<http://www.unicef.org/violencestudy/reports/S

G_violencestudy_en.pdf> Accessed 11 July

2012

Kompas, 2008b. Anal sex, highest of children

crime (Sadomi, kasus kejahatan anak

tertinggi).

http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2008/04/10/2

2173758/sodomi.kasus.kejahatan.anak.tertingg

i. Access 10 July, 2012.

Kompas, 2008c. Male teacher caught kissing

female students (Pak guru ciumi 7 murid

perempuan).

http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2008/11/04/1

0080790/Pak.Guru.Ciumi.7.Murid.Perempuan.

Access 10 July, 2012.

Lee, V.E., Croninger, R.G., Linn, E. And Chen,

X., 1996. The culture of sexual harassment in

secondary school. American Educational

Research Journal, 33: 383-417.

Pellegrini, A.D., 2002. Bullying, victimization,

and sexual harassment during the transition to

middle school. Educational Psychologist, 37/3:

151-163.

Primariantari, R. 1999. Women, violence, and

gang rape in Indonesia. Cardozo Journal of

International and Comparative Law, 7: 245276.

Wandita, G., 1998. The tears have not

stopped: Political upheaval, ethnicity, and

violence against women in Indonesia. Gender

and Development, 6/3: 34-41.

Wishnietsky, D.H., 1991. Reported and

unreported teacher-student sexual

harassment. The Journal of Education

Research, 83/3: 164-169.

United Nations (na) What is sexual harassment

<http://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/pdf/wha

tissh.pdf> Accessed 10 March 2012

United Nations. 2005. UNHCR’s Policy on

Harassment, Sexual Harassment, and Abuse

of Authority.

10

Research team members:

Australian Demographic and Social Research

Institute –Australian National University

(ADSRI-ANU):

Dr. Iwu Dwisetyani Utomo (Principal Investigator I)

Prof. Peter McDonald (Principal Investigator II)

Prof. Terence Hull

pregnancy and delivery; human growth and

development; reproductive technology; social aspects of

reproductive health; moving towards liberal culture and

its consequences; family institution; violence and sexual

crimes and religious aspects of reproductive health. The

coverage of each topic and the accuracy of the materials

provided in the textbook were evaluated by the team.

Consultant:

Prof. Saparinah Sadli

A content analysis was also performed using a gender

content analysis. Areas evaluated included: public and

domestic spheres; education and gender; social

leadership roles; arts; technology; roles in

environmental sustainability; violence and photos or

pictures used in the textbooks. All fields were evaluated

according to whether the material was male or female

dominated; mostly male or female content; and degree

of equality between males and females.

Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN)

Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta:

Dra. Ida Rosyidah, MA.

Dra. Tati Hartimah, MA.

Dr. Jamhari Makruf

Hasanuddin University:

Prof. Nurul Ilmi Idrus

Gender analysis was conducted by evaluating the text

and pictures used in Sport and Healthy Living

(PENJASKES); Science and Biology; Social Sciences and

Islamic Religion, Bahasa Indonesia and English Language

school textbooks for year 1,6, 9 and 12. In the second

stage a survey of Year 6 (N=1837) and Year 12 students

(N=6555), teachers (N=521) and school principals (N=59)

in Jakarta, West Java, West Nusa Tenggara and South

Sulawesi was conducted (N=8972) to evaluate

respondents’ understanding regarding reproductive

health and gender. The sampling of schools was

performed in several stages. First, in every province two

districts were selected, one urban and one rural. Two

public schools and two religious schools were selected in

each selected district that represented the best school

and a medium performing school. Thus in every

province, 16 schools were selected. In the selected

schools, all students in Years 6 and 12 participated in the

survey and filled in the self administered questionnaire

in class. The research team gave instructions and stayed

in class so that students may ask questions if they don’t

understand. Following the survey, qualitative in‐depth

interviews were conducted among school teachers and

principals, local religious leaders and policy makers. A

series of policy briefs will be developed from this study.

The research team was led by Dr. Iwu Dwisetyani Utomo

and Prof. Peter McDonald.

Correspondence: Iwu.Utomo@anu.edu.au or

Peter.McDonald@anu.edu.au

Description of the Study: Integrating Gender

and Reproductive Health Issues in the

Indonesian National School Curricula

In the first stage of this two‐stage study, content analysis

of more than 300 primary and secondary school textbooks

was undertaken on issues relating to reproductive and

sexual health education and gender. The second stage was

a school‐based survey conducted in Jakarta, West Java,

West Nusa Tenggara and South Sulawesi.

For the content analysis the team analysed the national

Curriculum to see if reproductive health was specifically

mentioned and searched for relevant words that

indicating content relevant to reproductive health issues.

After identifying in grades, subjects and semesters where

reproductive and sexual health information is given,

textbooks based on the curriculum from various

publishers were selected. School textbooks analysed

included: Sport and Healthy Living (PENJASKES); Science

and Biology; Social Sciences and Islamic Religion.

An evaluation module was developed for the analysis of

13 fields of reproductive and sexual health. These were:

genital hygiene; STDs; HIV and AIDS; female reproductive

problems; male reproductive health problems;

Acknowledgement: This policy brief is made possible by funding from the AusAID through the Australian Development

Research Award, Ford Foundation, ADSRI-ANU and the Indonesian National Planning Bureau-BAPPENAS.

Jakarta, 11 January 2012.

Australian Demographic and Social Research Institute

The Australian National University

Canberra ACT 0200, AUSTRALIA

http://adsri.anu.edu.au Enquiries: +61 2 6125 3629

11