THALIDOMIDE FOR SEVERE SYSTEMIC ONSET JUVENILE RHEUMATOID

ARTHRITIS: A MULTICENTER STUDY

THOMAS J. A. LEHMAN, MD, SHARON J. SCHECHTER, BS, ROBERT P. SUNDEL, MD, SHEILA K. OLIVEIRA, MD,

ANNA HUTTENLOCHER, MD, AND KAREN B. ONEL, MD

Thirteen children with difficult systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis were treated with thalidomide. At 6 months, 11 of

the 13 were able to reduce their use of prednisone (P < .002), with a concurrent improvement in erythrocyte sedimentation rate

(P < .0001) and an increase in hemoglobin level (P < 0.005). Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis improvement scores $50% were

obtained by 10 of the 13 children. (J Pediatr 2004;145:856-7)

hildren with severe systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (SoJRA) often have a poor outcome because of chronic

inflammation and corticosteroid side effects.1 Current alternatives to corticosteroids include autologous stem cell

transplantation, cyclosporine, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, intravenous gammaglobulin, etanercept, and infliximab.

None is consistently successful.2-6

Thalidomide is a unique anti-inflammatory agent that suppresses angiogenesis, cellular adhesion molecule expression, and

production of tumor necrosis factor-a and interleukin-6.7 We previously reported the use of thalidomide in 2 children with

SoJRA.8 This report includes 13 children with SoJRA treated at 4 institutions. Our findings suggest that thalidomide is a useful

corticosteroid-sparing agent with an acceptable level of side effects when used in low dosage.

C

METHODS

The patients were drawn from four different institutions (Hospital for Special

Surgery in New York, NY; Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Boston, Mass;

Universidade F Rio De Janeiro, Brazil; and the University of Wisconsin, School of

Medicine, Madison, Wis). Two were reported previously.8 Patients were selected for

inclusion because they had failed conventional therapy according to their attending

physicians.

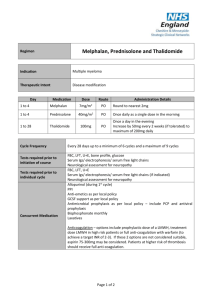

Thalidomide was given at an initial dose of 2 mg/kg per day, rounded to the nearest 50

mg. If no toxicity was noted in 2 weeks, the dose was increased to 3 to 5 mg/kg per day if

necessary (7 of 13 patients). Informed consent was obtained, and all US patients were entered into the system for Thalidomide education and prescribing safety (STEPS) program.9

Monthly visits included physical examination, joint count, complete blood count,

erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and biochemical profile. Prednisone dosage, thalidomide

dosage, and evidence of thalidomide toxicity were recorded at each visit. Statistical analysis,

including testing for normality and paired t tests, was performed with the use of GraphPad

InStat GraphPad Software, Inc (San Diego, Calif).

RESULTS

Seven girls and six boys with a mean age of 10.15 ± 1.66 years were included. All

patients were #16 years of age at the onset of SoJRA. When studied, their ages ranged

from 3 to 23 years. All patients were followed for 6 months. Prior therapy included

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, methotrexate, etanercept, and corticosteroids in all

cases. Five had received cyclosporine A and azathioprine and two had received

SoJRA

STEPS

856

Systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

System for Thalidomide education and prescribing safety

From the Division of Pediatric Rheumatology, Hospital for Special Surgery, and the Department of

Pediatrics, Sanford Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York,

New York; the Division of Immunology, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; Pediatric

Rheumatology, Universidade F Rio

De Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil;

and the Department of Pediatrics,

University of Wisconsin Medical

School, Madison, Wisconsin.

Dr Lehman is the recipient of a grant

from Celgene to measure cytokine

levels before, during, and after thalidomide therapy in children with systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid

arthritis.

Submitted for publication Mar 28,

2004; last revision received Jun 2,

2004; accepted Aug 4, 2004.

Reprint requests: Thomas J.A.

Lehman, MD, Division of Pediatric

Rheumatology, Hospital for Special

Surgery, 535 E 70th St, New York,

NY 10021. E-mail: goldscout@aol.

com.

0022-3476/$ - see front matter

Copyright ª 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights

reserved.

10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.020

cyclophosphamide. None had achieved adequate disease

control defined as a sustained rise in hemoglobin above 11

g/dL or reduction in erythrocyte sedimentation rate by at least

50% and absence of fever (present in 8 of 13), rash (9 of 13), or

other systemic manifestations.

Eleven of the 13 patients had a sustained response to

thalidomide with adequate disease control. Most showed

improvement within 4 weeks. For the 13 patients, the mean

prednisone dosage decreased from 14.8 ± 3.8 mg/d to 5.1 ± 2.3

mg/d (P < .002) over the 6 months, and 6 were able to

discontinue prednisone.

The mean erythrocyte sedimentation rate fell from 54 ±

8.2 to 23 ± 6.3 mm/h (P < .001.) In 7 of the 13 children, the

erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal after 6 months.

Ten of the 11 patients had a sustained rise in serum

hemoglobin. The mean serum hemoglobin concentration rose

from 10.4 ± 0.53 to 12.0 ± 0.40 g/dL (P < .005). Four patients

had a rise in serum hemoglobin level $2 g/dL.

The mean joint count fell from 19.1 ± 8.2 to 6.1 ± 2.6

(P = .07). No patient had a rise in joint count. Ten of the 13

children achieved JRA improvement scores $50%, according

to the criteria for the preliminary definition of improvement in

juvenile arthritis.10

Side effects were minor. No child had clinically evident

neurotoxicity. Short-lived paresthesiae (15 to 30 minutes)

manifested as numbness and tingling were common during the

first weeks of thalidomide administration. In all cases, the next

dose of thalidomide was held until these symptoms resolved.

All of the patients in the study were able to continue

thalidomide at the same (9 of 13) or a decreased dosage at the

investigator’s discretion. Sedation was a common effect.

Giving the daily dose at bedtime minimized inconvenience.

Improved sleep patterns were noted by families. Constipation

was reported by some but resolved with dietary adjustments.

Thalidomide is a well-known teratogen. All subjects of

reproductive age agreed to use effective forms of birth control

and were carefully monitored for possible pregnancy according

to the STEPS protocol. No patient became pregnant during

the course of this study.

DISCUSSION

This report expands our report of two SoJRA children

who improved dramatically with thalidomide.8 It documents

the efficacy of thalidomide in 11 additional children with

SoJRA at varied institutions treated by different physicians.

Previously, all had failed conventional therapy.

Children receiving thalidomide must be monitored for

prolonged paresthesiae or other evidence of neurotoxicity.

Several children in this series had brief paresthesiae, but none

required discontinuation of thalidomide. Sedative effects and

constipation remain manageable concerns. Thalidomide is

well known as a teratogen and must not be used by women

who are at risk of becoming pregnant. This risk is not present

in young children and can be minimized in adolescents by

rigorous use of the STEPS protocol. These potential side

effects suggest that thalidomide should be restricted to

Thalidomide for Severe Systemic Onset Juvenile Rheumatoid

Arthritis: A Multicenter Study

children with SoJRA who are inadequately responsive to

other agents.

Thalidomide is the progenitor of a novel class of

immunomodulatory agents that downregulate the inflammatory mediators tumor necrosis factor-a, interleukin-6, and

nuclear factor-kB as well as affecting angiogenesis, apoptosis,

and endothelial cell signaling.11 New derivatives termed

ImiDs, which appear to share the anti-inflammatory activities

of thalidomide without the teratogenic or sedative effects or

neurotoxicity, are under active investigation.7,11

In summary, we report beneficial effects of thalidomide

in 11 of 13 children with severe SoJRA who had failed

previous therapy. Although the risk of toxicity from

thalidomide is real, none of our patients had deleterious side

effects. The risks of the low dosage of thalidomide used in this

study are acceptable when compared with the permanent

physiologic and psychologic sequelae associated with prolonged high-dose corticosteroid therapy. Further, the possible

toxicities of thalidomide are small when compared with those

of autologous stem cell transplantation and other proposed

salvage therapies for severe SoJRA. Until a larger controlled

study is completed, therapy with thalidomide should be

reserved for those children with SoJRA who have failed

conventional therapy.

REFERENCES

1. Lomater C, Gerloni V, Gattinara M, Mazzotti J, Cimaz R, Fantini F.

Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a retrospective study of 80

consecutive patients followed for 10 years. J Rheumatol 2000;27:491-6.

2. Wulffraat NM, Brinkman D, Ferster A, Opperman J, ten Cate R,

Wedderburn L, et al. Long-term follow-up of autologous stem cell

transplantation for refractory juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Bone Marrow

Transplant 2003;32(Suppl 1):S61-4.

3. Silverman ED, Cawkwell GD, Lovell DJ, Laxer RM, Lehman TJA,

Passo MH, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of systemic

juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized placebo controlled trial: Pediatric

Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2353-8.

4. Wallace CA, Sherry DD. Trial of intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide

and methylprednisolone in the treatment of severe systemic-onset juvenile

rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1852-5.

5. Shaikov AV, Maximov AA, Speransky AI, Lovell DJ, Giannini EH,

Solovyev SK. Repetitive use of pulse therapy with methylprednisolone and

cyclophosphamide in addition to oral methotrexate in children with systemic

juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: preliminary results of a long-term study.

J Rheumatol 1992;19:612-6.

6. Gattorno M, Buoncompagni A, Faraci M, Pistoia V. Early treatment of

systemic onset juvenile chronic arthritis with low-dose cyclosporin A. Clin

Exp Rheumatol 1995;13:409-10.

7. Weber D. Thalidomide and its derivatives: new promise for multiple

myeloma. Cancer Control 2003;10:375-83.

8. Lehman TJA, Striegel KH, Onel KB. Thalidomide therapy for

recalcitrant systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Pediatr 2002;140:

125-7.

9. Zeldis JB, Williams BA, Thomas SD, Elsayed ME. STEPS:

a comprehensive program for controlling and monitoring access to

thalidomide. Clin Ther 1999;21:319-30.

10. Giannini EH, Ruperto N, Revelli A, Lovell DJ, Felson DT, Martini A.

Preliminary definition of improvement in juvenile arthritis. Arthritis Rheum

1997;40:1202-9.

11. Dredge K, Marriot JB, Dalgliesh AG. Immunological effects of

thalidomide and its chemical and functional analogs. Crit Rev Immunol

2002;22:425-37.

857