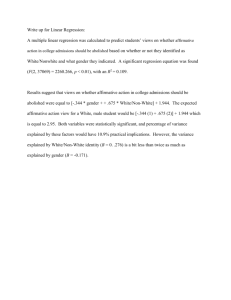

Affirmative Action - Institute for Research on Poverty

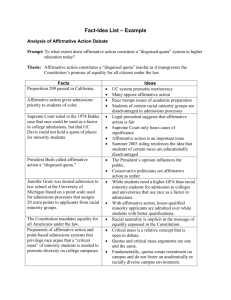

advertisement