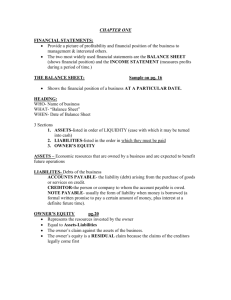

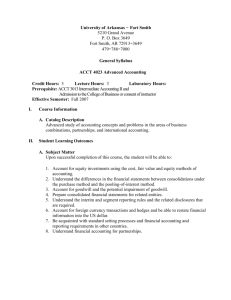

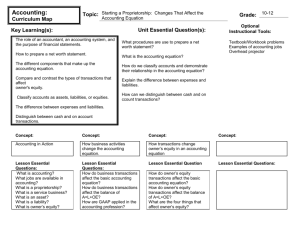

Financial Accounting 3: Module 1 course notes

advertisement