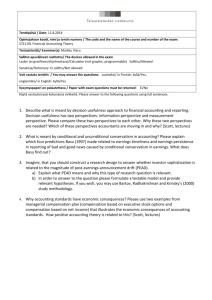

Empirical research on accounting choice

advertisement