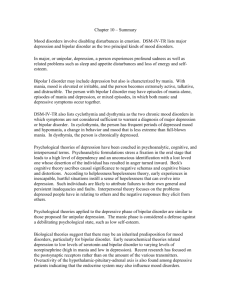

Depressive personality styles and bipolar spectrum disorders

advertisement