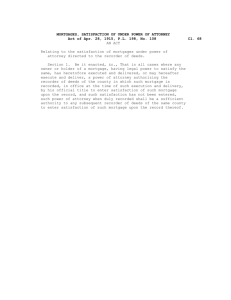

uniform residential mortgage satisfaction act

advertisement