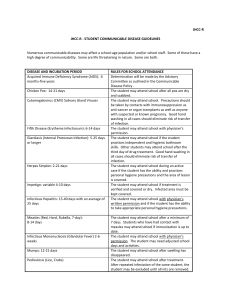

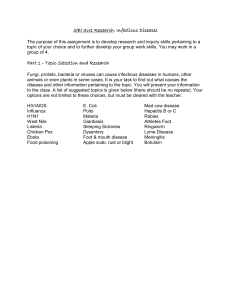

1.1 The scope and concerns of public health

advertisement