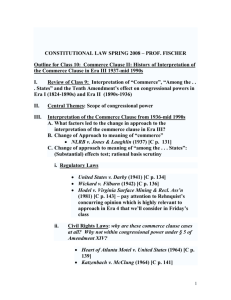

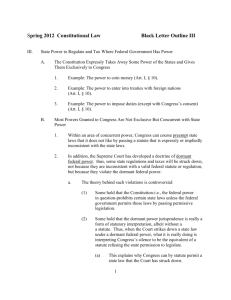

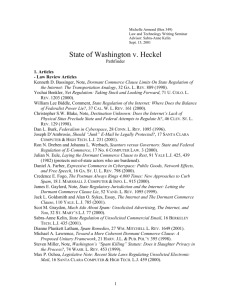

The Dormant Commerce Clause and the Internet

advertisement