- Kritika Kultura

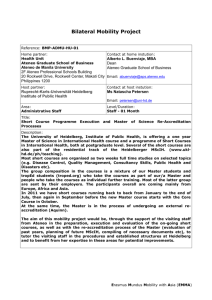

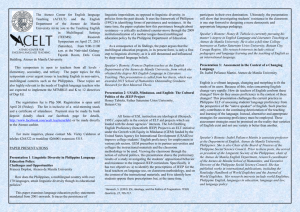

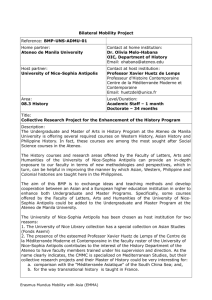

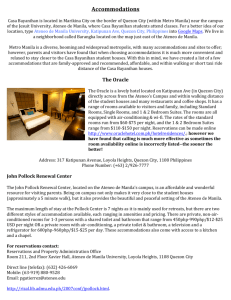

advertisement