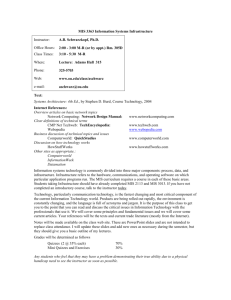

Notes on Leveraged Buyouts

advertisement

Notes on Leveraged Buyouts 1 What Is a Leveraged Buyout? • The acquisition by a small group of investors of a public or private company, financed primarily with debt. – “Taking the company private.” • This financing technique can be used by a variety of entities, including the managers of a corporation (MBO), or outside groups, such as other corporations or investment groups (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, Blackstone, Thomas H. Lee etc.). 2 1 Advantages of LBOs • Tax shields associated with heavy debt financing. • Freedom of being a private firm – long-term orientation. • Better incentive alignment of management. • Efficiency improvement. 3 LBOs in the 1980s Kaplan (1989) • 76 LBOs from 1979 – 1986. – Average size: BV of total assets = $535M. • Shareholders receive a premium of 45% (on average). • Leverage increases from 20% pre-buyout to 86% postbuyout. • Management ownership. – % equity stake go up (9% to 30% on average for all managers). – $ ownership declines (from $25M to $16M on average) • Managers cash out on average!!! • 48 of 76 LBOs go public before 1989. – These successful MBOs had large increases in operating performance and reductions in CAPX. 4 2 The Evolution of the LBO Market • LBO boom in the late 1980s and bust in early 1990s. – Buyout volume raises from $1 billion in 1980 to $60 billion in 1988. – It drops dramatically to $4 billion in 1990. • Default rates increase over time. – 2% for LBOs done between 1980-1984 and 30% for 1985-1989. • The use of junk bonds to finance LBOs increases over time. – Only one pre-1985 LBO uses junk bonds (55% of post-1985 LBOs). • Managerial participation in LBOs. – Managers cash-out more in the post-1985 LBOs. LBOs in the 1990s to Present 5 Cao and Lerner (2009) • The buyout industry is far larger and deals are getting larger. – Fundraising by US buyout funds in 2005 is nine times of 1987 level. • The returns for these investments deteriorated. – LBO funds in the 1980s earned annual return of 47%. – LBO funds in the 1990s earned just over 10%. • There is increased competition for transactions. – Auctions by sellers. – Consortium by potential buyers. – Higher risk of securing a deal. • Higher equity contribution by buyout firms. 6 3 Market Trends in Private Equity Buyouts Axelson et al. (2009) 7 Market Trends in Private Equity Buyouts Axelson et al. (2009) 8 4 Sources of Funds for LBOs • Typically, the merchant bank invites Targetco’s management to purchase some of the stock of Shellco. • LBOs are generally friendly transactions. • Some debt will be bank loans, most senior. • The rest will come from private placements with other lenders, or from public debt issues (non-investment grade). 9 An LBO Financing Example • Wavell Corp, a manufacturer of glassware was bought by Eastern Pacific, a conglomerate in the 1970s. • In 1983, Wavell management considered an MBO. • Sales $7 million, EBIT $650k, Net Income $400k. • The purchase price was $2 million. – Banks supplied $1.2 million of senior debt at an interest rate of 13%, secured by Wavell’s inventory and PPE. – An insurance company made a loan of $.6 million, subordinate debt. – The same insurance company had an equity position of $.1 million. – The Wavell management team put up $.1 million as their own equity position. 10 5 11 Interest Rates on LBO Debt Funding Axelson et al. (2009) Note: The spread is relative to LIBOR. 12 6 Debt Service on LBO Debt Funding Axelson et al. (2009) 13 Which Companies Are Good LBO Candidates? • Steady and predictable cash flow – Free Cash Flow. • Clean balance sheet with little debt and strong asset base. • Strong market position. • Divestible assets. • Strong management team. • Potential for expense reduction. • Viable exit strategy. 14 7 Potential Problems with LBOs • Bankruptcy risk. • Leverage can induce firms to choose overly risky projects. • Underinvestment. • Passing up good projects. 15 Strategic Effects of LBOs • A firm’s capital structure can affect its operations and investment decisions. – High leverage can increase costs of financial distress, impact firm’s ability to invest. • Debt (and capital structure more generally) can also affect the way competing firms interact. 16 8 Leverage and Competitive Strategy • Several possibilities may arise: – High debt firms may invest less. – Increasing leverage may cause a firm to pursue more aggressive pricing strategies in order to capture a larger market share. – But if leverage is too high, it may also encourage competitor firms to react aggressively. 17 In a Nutshell • Synergy-related explanation: – If a conglomerate is inefficient, then taking a division private and making it independent of the parent creates value. • Leverage-related explanations: – Tax advantage of debt financing. – Wealth transfers from creditors to shareholders (the LBO increases the risk of debt). 18 9 Valuation of LBOs • Free Cash Flow: Calculate FCF and discount by the WACC. • Problem: LBO’s are highly leveraged transactions in which we expect the capital structure to change rapidly. • Investors are usually expected to pay off outstanding principal according to a specific timetable ==> The firm’s debt/equity ratio falls over time, in a predictable way. • WACC approach is better for valuing situations where the debt/equity ratio remains constant. 19 Valuation of LBOs • Adjusted Present Value Approach (APV): Calculate NPV of the all-equity financed firm and add the value of the tax benefits of debt. • Advantage: This method calculates separately the value created by the project and the value created by the financing. • For this reason, it is easy to apply to a firm whose capital structure is changing over time. 20 10 The LBO Formula • Take a firm private. • Fund by borrowing against assets. • Sell off pieces to pay down debt. • Exit. – Sale. – Re-capitalization. – Come full circle with an IPO of the core – Reverse LBOs (RLBOs). LBOs and RLBOs Year RLBOs LBOs 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Total 3 1 0 10 3 11 26 34 3 5 12 39 67 40 28 18 26 37 28 33 29 22 21 496 17 15 15 46 112 153 235 212 298 299 191 181 218 180 178 209 194 202 177 183 296 167 154 3915 VC-Backed IPOs 31 77 30 138 58 46 99 75 39 40 42 113 124 176 121 178 253 127 71 261 219 44 32 2,394 Total IPOs 73 189 73 475 190 198 456 305 116 113 97 227 299 473 340 389 565 417 272 440 349 75 71 6,202 RLBO as fraction of LBOs 17.65% 6.67% 0.00% 21.74% 2.68% 7.19% 11.06% 16.04% 1.01% 1.67% 6.28% 21.55% 30.73% 22.22% 15.73% 8.61% 13.40% 18.32% 15.82% 18.03% 9.80% 13.17% 13.64% 12.67% 21 Cao and Lerner (2009) RLBO Share of VCBacked IPOs 9.68% 1.30% 0.00% 7.25% 5.17% 23.91% 26.26% 45.33% 7.69% 12.50% 28.57% 34.51% 54.03% 22.73% 23.14% 10.11% 10.28% 29.13% 39.44% 12.64% 13.24% 50.00% 65.63% 20.72% RLBO Value Share of All IPO Value 1.43% 2.45% 0.00% 0.73% 9.78% 16.17% 9.87% 2.15% 6.94% 13.87% 60.21% 40.47% 14.41% 4.15% 9.49% 10.96% 10.74% 15.96% 17.26% 12.28% 2.99% 11.24% 16.12% 13.17% RLBO Share of All IPOs 4.11% 0.53% 0.00% 2.11% 1.58% 5.56% 5.70% 11.15% 2.59% 4.42% 12.37% 17.18% 22.41% 8.46% 8.24% 4.63% 4.60% 8.87% 10.29% 7.50% 8.31% 29.33% 29.58% 8.00% 22 11 RLBOs versus IPOs RLBOS 1980 1981 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 AVG Gross Procee ds (Million ) 15.00 23.40 53.11 21.03 19.40 37.79 44.61 55.23 46.24 38.79 59.94 65.60 77.57 66.23 89.05 118.20 112.72 134.54 147.01 163.89 148.13 202.62 79.09 Underpricing (Percentag e) Total Debt/Capitali zation After IPOs 4.09 10.39 -0.14 3.21 16.37 14.00 9.08 10.44 9.37 5.81 13.48 11.92 42.72 54.21 31.67 15.06 10.30 15.41 20.01 49.21 33.17 56.38 53.98 53.28 61.73 46.29 59.28 58.06 45.79 49.08 47.16 44.01 32.05 54.93 39.65 40.72 51.18 34.29 38.58 36.52 47.87 Cao and Lerner (2009) Non-Buyout backed IPOs Total UnderGross Debt/Cap pricing Proceeds italization (Perce (Million) After ntage) IPOs 13.70 29.30 12.76 23.32 23.06 33.95 13.94 37.29 33.59 39.13 30.59 70.77 41.53 31.38 32.76 37.90 34.57 49.91 40.76 33.72 56.24 31.45 40.95 28.50 25.60 43.87 32.44 24.76 49.14 13.64 26.20 59.33 14.91 27.38 56.27 13.86 30.33 56.55 28.27 22.81 54.81 20.29 23.15 70.92 15.16 22.54 62.30 22.04 24.60 80.26 73.00 13.77 64.77 61.25 9.41 142.38 15.34 20.34 145.53 9.24 27.52 52.47 32.80 27.84 23 Characteristics of RLBOs Cao and Lerner (2009) Mean Median Standard Deviation Min Max 6.87 3.08 3.55 0.17 27.25 2876.18 1258.40 4426.83 2.8 27582.4 14.22 13 7.95 1 41 55.3% 52.6% 26.4% 5% 100% 37.9% 36.2% 20.5% 0% 85.1% 44.0% 42.9% 20.6% 0% 100% Director/Management Ownership Before IPO 66.2% 68.5% 23.2% 6.9% 100% Director/Management Ownership After IPO 36.0% 35.1% 26.8% 0% 86.9% 29.19% 0 46.56% 0 1 14.09% 0 24.81% 0 1 Years of staying private after LBO Buyout Group Capital Managed Prior to RLBO ($ Million) Buyout Group Age Before RLBO Buyout Group Ownership Before IPO Buyout Group Ownership After IPO Board Share of Buyout Group Chairman from Buyout group CEO, President, and Chairman from Buyout Group 24 12 RLBO Performance Cao and Lerner (2009) Average Monthly Excess Return (Equal Weighted) 0.60% 0.40% 0.20% 0.00% 1 -0.20% 2 3 4 5 -0.40% -0.60% 25 RLBO Performance Cao and Lerner (2009) Average Monthly Excess Return (Value Weighted) 2.00% 1.50% 1.00% 0.50% 0.00% 1 2 3 4 5 26 13 Summary of RLBO Performance Cao and Lerner (2009) • RLBOs appear to consistently outperform other IPOs and the market as a whole. • No evidence of a deterioration of returns appears over time. • RLBOs sharply outperform the market in the first, fourth, and fifth year after going public. • Much of the outperformance seems associated with the larger RLBOs. • There is no evidence that more leveraged RLBOs perform more poorly than their peers. 27 Appendix: Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. 28 14 Who we are? • KKR, one of the world’s largest and most successful private equity firms, has completed buyout transactions that are among the most complex in history. The firm’s investment approach, however, is fundamentally simple: KKR acquires industry-leading companies and works with management to grow and improve them and thereby create shareholder value. • Established in 1976 and led by co-founding members Henry Kravis and George Roberts, KKR has completed more than 150 transactions with an aggregate enterprise value of over $279 billion. As of December 31, 2006, KKR’s equity investments were valued at over $74 billion on over $30 billion of invested capital, a multiple of 2.5 times. Our investors include corporate and public pension plans, financial institutions, insurance companies, and university endowments. 29 Our principles • KKR operates as an investment firm, not as a conglomerate or a holding company. Each company in our portfolio is independently managed and financed. Each has its own board of directors, which includes KKR representatives. There are no cross-holdings. Cash flow from one company cannot be used in another company. • We are "involved," patient investors, not traders. The average time period we own a company is eight years, although a number of investments have exceeded ten years. • We take a long-term view of a company's performance. We are never concerned with quarter-to-quarter results, but rather focus on cash flow and look at results over a number of years. • Management is our partner in creating value. Our portfolio company managers have a significant amount of their personal net worth invested in their companies because we believe strongly that the best managers think like - and are - owners. 30 15 A time-tested approach to build value • KKR’S goal since its founding has been to achieve high rates of return for the KKR Funds by investing large amounts of capital for long-term appreciation. • KKR has executed management buyouts of large, mature companies; taken leveraged "build-ups" from having no assets at all into the Fortune 500; made acquisitions in traditional growth industries; pioneered leveraged investments in such novel fields as reinsurance and resort properties; created stand-alone, independent companies from large corporate parents; and made equity infusions to restructure highly leveraged public companies, setting new standards for creativity, innovation and flexibility in the process. • ….KKR’s long-standing recognition of the fact that the closing of an acquisition is only the beginning of the process of delivering value. For KKR, success in private equity investing depends not only on identifying and consummating acquisitions, but also cultivating and nurturing them. • ….. after a deal is done and the headlines are gone, KKR embarks on years of diligent work along with the managements of its portfolio companies to realize the full potential of its acquisitions. 31 Deal origination • KKR evaluates hundreds of potential investments each year. Once an opportunity has been identified, KKR employs a number of strategies to secure a transaction. Whenever possible, KKR works with companies and managers on an exclusive basis to develop transactions, as it has done with several of its portfolio companies. • Management teams at existing KKR companies often provide pivotal assistance by lending their expertise and judgment in identifying and assessing opportunities. Together, these capabilities enable KKR to analyze large, multi-faceted, multi-billion dollar enterprises that few others would be able to review adequately. 32 16 Structuring and financing transactions • ……KKR’s transactional capabilities are enhanced by its significant presence in the capital markets. Throughout its history, KKR has been able, regardless of prevailing market conditions or available financing sources, to engineer the largest, most complex and most advantageous financings in the marketplace. No buyout group has more experience raising bank debt, high-yield debt or equity in the marketplace, and because of the scope of its activities, KKR has typically been able to receive the best possible financing terms. 33 Overseeing portfolio companies (I) • Over the years, KKR’s involvement in helping its companies enhance shareholder value has become widely recognized, and the manner in which KKR executives fulfill their roles as active directors has been viewed, by many, as a model of effective corporate governance. The expertise KKR brings to its portfolio companies includes • Attracting Strong Management • Management and Employee Incentivization -- In addition to attracting talented executives, KKR has been an innovator in its work to structure management incentives and compensation plans that align the interests of management and shareholders. A requirement of engagement for all managers of KKR companies is that they make a significant investment in their businesses, sharing directly in both the rewards and risks of equity ownership. 34 17 Overseeing portfolio companies (II) • Helping Portfolio Companies Arrange Financings -KKR continually seeks to optimize the capital structure of each portfolio company. With KKR’s assistance, virtually every one of its portfolio companies has been able to access efficient sources of capital over time. At the appropriate time, KKR has taken a number of companies public, generally using proceeds to deleverage and reduce the inherent risk for KKR and its investors. KKR’s level of involvement does not change after the offering; KKR typically remains a controlling shareholder and continues its oversight role, assisting in the formulation of strategy and evaluating management. Such efforts tend to translate into superior results, with many of KKR’s companies outperforming their industry peers after they go public. 35 Overseeing portfolio companies (III) • Providing Effective Oversight -- The core oversight role that KKR plays on a day-to-day basis through its position on the Boards of Directors of its portfolio companies is vitally important. KKR works closely with each management to put into place a rigorous infrastructure to monitor corporate results on a consistent and continual basis. The objective is to instill a discipline that translates into predictable and superior performance. • Maximizing Value When Exiting Investments -- The duration of the average KKR investment is typically five to ten years, with the firm’s exit strategy being the final step in generating value. KKR seeks to maximize the value it can obtain through its exit strategy by carefully selecting the timing and method of sale. 36 18