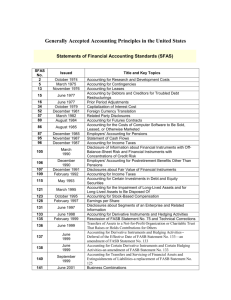

The Impact of the SEC on the First 100 Statements of the FASB

advertisement