Darkness over Hawaii: The Annexation Myth Is the Greatest

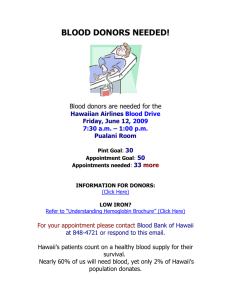

advertisement