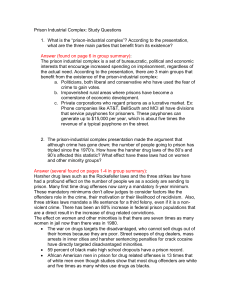

Sentencing And Corrections In The 21st Century: Setting The Stage

advertisement