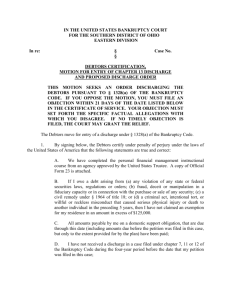

Individual Chapter 11 - National Conference of Bankruptcy Judges

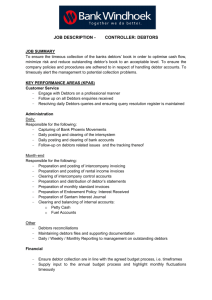

advertisement