Cherokee Readings PDF

advertisement

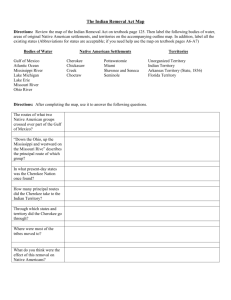

Meyer Individuals and Society Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears Overview by Dr. Meyer (from learnnc.org, georgiatribeofeasterncherokee.com, wsharing.com, wikimapia.org, wikipedia.org, Worcester v. Georgia at oyez.org, and other sources) 1. Cherokee culture derives from the Mississippian (Moundbuilders) and the Pisgah cultures that settled in what is now the southeastern United States in the first half of the second millennium A.D. (c. 1000-1500). The first town known to be Cherokee, Dugilyui (or Tugaloo, by the English), dates from about 1450. Mounds still exist at the site in Tugaloo State Park in Georgia. The first European contact with the Cherokee dates from the Spaniard De Soto’s mission (1540) that resulted in the “discovery” of the Mississippi River. A hundred years later, the English settlers of North America regularly traded with the Cherokee. This contact eventually brought small pox to the tribe (as it did other Amerindians), devastating the Cherokee—an epidemic in the 1730s killed as many as 50% of the population. By 1805, the Cherokee numbered only about 12,000. 2. Relations between the Cherokee and the Americans varied over the next century as suited the tribe. During the Yamasee War (1730s SC and NC) the Cherokee stayed neutral; when Creek emissaries came to negotiate an alliance against the Carolinians the Cherokee listened patiently and then killed each of the Creek envoys. During the French and Indian War, the Cherokee initially helped the British against the Shawnee, but later turned against them, leading raiding parties along the Appalachian backcountry including an attack on Fort Dobbs. The tribe sided with the British against the Americans during the War of Independence, but during the Creek War (1813-1814) formed a strong alliance with the Americans. With Cherokee help, the Americans, led by Andrew Jackson defeated the Creeks in Alabama at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. After the battle, Jackson promised Chief Junaluska (who literally saved Jackson’s life in an attack by a Creek prisoner) that the Cherokee would live forever on their traditional land. “As long as the sun shines and the grass grows,” Jackson exclaimed, “there shall be friendship between us, and the feet of the Cherokee shall be toward the east.” 3. Whether Jackson meant it or not, it was unlikely that the promise would be fulfilled; for the U.S. had already begun planning for the eventual takeover of Indian lands. Treaties signed in the 1780s and 1790s punished the Cherokee for siding with Britain and forced them to cede land. The U.S. wanted them either to assimilate or leave. The Treaty of Holston (1795) tried to facilitate assimilation by giving the Indians farm implements and building a road through the territory. The treaty read: “That the Cherokee nation may be led to a greater degree of civilization, and to become herdsmen and cultivators, instead of remaining in a state of hunters, the United States will from time to time furnish gratuitously the said nation with useful implements of husbandry, and further to assist the said nation in so desirable a pursuit.” Jackson himself negotiated a similar treaty in 1817. Given the choice of adopting European ways or moving beyond the limits of the U.S., many Cherokee chose the latter. 4. By the 1820s, many Cherokee who had stayed in the East adopted cultural and economic patterns of whites. In return for ceding [cede] land, the U.S. paid the Cherokee in farm implements. Some Cherokee farms grew into small plantations, worked by black slaves—a 1809 census counted 583 “Negro slaves” living in the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee built gristmills, sawmills, and blacksmith shops, encouraged missionaries to set up English language schools to educate their children, and used a syllabary developed by Sequoyah to translate English to Cherokee to encourage literacy. Under the leadership of Major Ridge and John Ross, they built a new capitol for the Cherokee Nation, at New Echota in Georgia, and began developing a written constitution, modeled after the U.S. Constitution. 5. The Cherokee might have held off white settlement, but two things happened in 1829 to work against them. First, Andrew Jackson became President of the United States and a year later call for Indian removal. The Indian Removal Act passed Congress in May 1830. The law ordered the removal of all Indian nations in the southeastern U.S. to land in the “Great American Desert” beyond the Arkansas River. Although it was a betrayal of Jackson’s promise to Chief Junaluska, one Jackson biographer, Robert Remini, insists Jackson acted to save the Indians from annihilation. Remini argues that the states and settlers would have taken the Indian lands regardless and so Jackson’s actions made sure that the Indians would get something for their land and would be safely removed. He has a point. The law was very popular among whites living in the region because it opened up new land for their development. But it was not without its critics, including from the likes of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, and vociferously by New Jersey Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen (1844 Whig candidate for Vice President), as well as from religious groups, notably the Quakers and Moravians. Meyer Individuals and Society Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears 6. Secondly, gold was discovered on Cherokee lands. It was only a matter of time before prospectors would be swarming in. Desirous of controlling the gold mining, the State of Georgia enacted a series of laws (December 1830) imposing its will on the Cherokee. Asserting its sovereignty over the lands within its borders, Georgia barred the Cherokee from holding tribal council or in any other way attempting to govern themselves. They were prohibited from selling or renting their land, except to the State, as well as from mining for gold. Georgia also ordered a general survey of Cherokee land (and Creek land in southern Georgia) for the purpose of preparing for an eventual lottery, giving away vacated Indian land. 7. Cherokee leaders successfully challenged Georgia in the U.S. Supreme Court. On advice from Frelinghuysen, the Cherokee hired former U.S. Attorney General William Wirt to lead their case. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the case for lack of standing, but the Cherokee won in the case of Worcester v. Georgia. The opinion, written by Chief Justice John Marshall, declared the Georgia laws unconstitutional. Georgia did not have the authority to bring the Cherokee under its control because while it resided within the boundaries of the state, “the Cherokee nation [was] a distinct community occupying its own territory [and all interaction] between the United States and this nation, [was], by our constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States.” Despite the Court’s decision, President Jackson sided with Georgia. He famously replied to the ruling, “Mr. Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” 8. Most Cherokee wanted to stay on their land, but some saw this as the final straw. Led by Major Ridge, they called for the tribe to negotiate a new treaty wherein they would accept removal and receive proper compensation. They formed a Treaty Party and presented a resolution to discuss the plan to the Cherokee National Council in October 1832. It was defeated. Principal Chief John Ross led the majority opposing any further cessions of land. The U.S. government submitted a new treaty to the Cherokee National Council in 1835. John Ross persuaded the council not to approve the treaty. He continued to negotiate with the federal government, trying to strike a better bargain for the Cherokee people, but deep divisions remained within the tribe. In December 1835, the U.S. resubmitted the treaty to a rump meeting of Cherokee at New Echota. Twenty men, none of them elected officials of the tribe, signed the treaty, ceding all Cherokee territory east of the Mississippi to the U.S. in exchange for $5 million and new homelands in Indian Territory. Despite protests by Cherokee and whites, alike, the Senate ratified the treaty in May 1836 by a single vote. 9. In December 1837, the U.S. government informed the Cherokee that the clause in the Treaty requiring them to “remove to their new homes within two years from the ratification of the treaty” would be enforced. The following May, President Van Buren sent General Winfield Scott to lead the expulsion. Federal troops and state militia began to move the Cherokee into stockades. Three groups left in the summer, traveling from present-day Chattanooga by rail, boat, and wagon, primarily on the water route, but many still awaited removal. Conditions in the stockades deteriorated. Food, water, medicine, and clothing were in short supply. Diseases raged through the camps. Many died. Those travelling over land were delayed by a summer drought and did not begin their trek until the fall. In October and November, 12 groups, each led by a respected Cherokee leader and accompanied by a doctor, and sometimes a missionary, set off on an 800 mile-journey overland to the west. Most were on foot; those riding in the wagons were usually only the sick, the aged, children, and nursing mothers with infants. They were heading north in winter. The route was chosen because of dependable ferries over the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and a well-travelled road between the rivers, but it turned out to be the more difficult. Heavy autumn rains washed away roads; scarcity of game made hunting futile. The last detachments did not arrive in the west until March. No one knows exactly how many Cherokee on the Trail of Tears—estimates suggest that between a fifth and as many as a quarter of their population (perhaps 3,000). The U.S. never paid the $5 million it promised. ASSIGNMENT: In your group, complete the vocabulary (underlined words/phrases) and then divide up the readings and answer the questions. Discuss your answers with each other and submit one copy of your answers. Reading #1: Jackson Message to Congress ‘On Indian Removal’ 1. Giving specific examples of tone and word choice, what is Jackson’s general attitude toward Indians? 2. Giving specific evidence from the document, what were the advantages of Indian removal to the United States? 3. Giving specific evidence from the document, what were the advantages of Indian removal to the Indians? Meyer Individuals and Society Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears 4. Could Jackson be wrong about the importance of ancestral land to the Indians, as opposed to Americans? Discuss. Reading #1: Transcript of President Andrew Jackson's Message to Congress 'On Indian Removal' (1830) Andrew Jackson's Annual Message http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=25&page=transcript It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation. Two important tribes have accepted the provision made for their removal at the last session of Congress, and it is believed that their example will induce the remaining tribes also to seek the same obvious advantages. The consequences of a speedy removal will be important to the United States, to individual States, and to the Indians themselves. The pecuniary advantages which it promises to the Government are the least of its recommendations. It puts an end to all possible danger of collision between the authorities of the General and State Governments on account of the Indians. It will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters. By opening the whole territory between Tennessee on the north and Louisiana on the south to the settlement of the whites it will incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier and render the adjacent States strong enough to repel future invasions without remote aid. It will relieve the whole State of Mississippi and the western part of Alabama of Indian occupancy, and enable those States to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power. It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community. What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization and religion? The present policy of the Government is but a continuation of the same progressive change by a milder process. The tribes which occupied the countries now constituting the Eastern States were annihilated or have melted away to make room for the whites. The waves of population and civilization are rolling to the westward, and we now propose to acquire the countries occupied by the red men of the South and West by a fair exchange, and, at the expense of the United States, to send them to land where their existence may be prolonged and perhaps made perpetual. Doubtless it will be painful to leave the graves of their fathers; but what do they more than our ancestors did or than our children are now doing? To better their condition in an unknown land our forefathers left all that was dear in earthly objects. Our children by thousands yearly leave the land of their birth to seek new homes in distant regions. Does Humanity weep at these painful separations from everything, animate and inanimate, with which the young heart has become entwined? Far from it. It is rather a source of joy that our country affords scope where our young population may range unconstrained in body or in mind, developing the power and facilities of man in their highest perfection. These remove hundreds and almost thousands of miles at their own expense, purchase the lands they occupy, and support themselves at their new homes from the moment of their arrival. Can it be cruel in this Government when, by events which it can not control, the Indian is made discontented in his ancient home to purchase his lands, to give him a new and extensive territory, to pay the expense of his removal, and support him a year in his new abode? How many thousands of our own people would gladly embrace the opportunity of removing to the West on such conditions! If the offers made to the Indians were extended to them, they would be hailed with gratitude and joy. And is it supposed that the wandering savage has a stronger attachment to his home than the settled, civilized Christian? Is it more afflicting to him to leave the graves of his fathers than it is to our brothers and children? Rightly considered, the policy of the General Government toward the red man is not only liberal, but generous. He is unwilling to submit to the laws of the States and mingle with their population. To save him from this alternative, or perhaps utter annihilation, the General Government kindly offers him a new home, and proposes to pay the whole expense of his removal and settlement. Meyer Individuals and Society Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears Reading #2: Chief John Ross protests the Treaty of New Echota 1. What words did Ross use to describe the U.S. government? 2. According to Ross, who were the people who signed the treaty? Did they have the authority to sign the treaty? 3. If the majority of Cherokee had not agreed to the removal, and if the proper government procedures, as outlined in the Cherokee constitution had not been followed, why did the U.S. insist the treaty was valid? Chief John Ross protests the Treaty of New Echota Letter from Chief John Ross to the Senate and House of Representatives, from Red Clay Council Ground, Cherokee Nation, September 28, 1836. In Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Papers of Chief John Ross, Volume 1, 1807–1839 (University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, Oklahoma, 1985). (http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newnation/4500) It is well known that for a number of years past we have been harassed by a series of vexations, which it is deemed unnecessary to recite in detail, but the evidence of which our delegation will be prepared to furnish. With a view to bringing our troubles to a close, a delegation was appointed on the 23rd of October, 1835, by the General Council of the nation, clothed with full powers to enter into arrangements with the Government of the United States, for the final adjustment of all our existing difficulties. The delegation failing to effect an arrangement with the United States commissioner, then in the nation, proceeded, agreeably to their instructions in that case, to Washington City, for the purpose of negotiating a treaty with the authorities of the United States. After the departure of the Delegation, a contract was made by the Rev. John F. Schermerhorn, and certain individual Cherokee, purporting to be a “treaty, concluded at New Echota, in the State of Georgia, on the 29th day of December, 1835, by General William Carroll and John F. Schermerhorn, commissioners on the part of the United States, and the chiefs, headmen, and people of the Cherokee tribes of Indians.” A spurious Delegation, in violation of a special injunction of the general council of the nation, proceeded to Washington City with this pretended treaty, and by false and fraudulent representations supplanted in the favor of the Government the legal and accredited Delegation of the Cherokee people, and obtained for this instrument, after making important alterations in its provisions, the recognition of the United States Government. And now it is presented to us as a treaty, ratified by the Senate, and approved by the President [Andrew Jackson], and our acquiescence in its requirements demanded, under the sanction of the displeasure of the United States, and the threat of summary compulsion, in case of refusal. It comes to us, not through our legitimate authorities, the known and usual medium of communication between the Government of the United States and our nation, but through the agency of a complication of powers, civil and military. By the stipulations of this instrument, we are despoiled of our private possessions, the indefeasible property of individuals. We are stripped of every attribute of freedom and eligibility for legal self-defence. Our property may be plundered before our eyes; violence may be committed on our persons; even our lives may be taken away, and there is none to regard our complaints. We are denationalized; we are disfranchised. We are deprived of membership in the human family! We have neither land nor home, nor resting place that can be called our own. And this is effected by the provisions of a compact which assumes the venerated, the sacred appellation of treaty. We are overwhelmed! Our hearts are sickened, our utterance is paralized, when we reflect on the condition in which we are placed, by the audacious practices of unprincipled men, who have managed their stratagems with so much dexterity as to impose on the Government of the United States, in the face of our earnest, solemn, and reiterated protestations. The instrument in question is not the act of our Nation; we are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people. The makers of it sustain no office nor appointment in our Nation, under the designation of Chiefs, Head men, or any other title, by which they hold, or could acquire, authority to assume the reins of Government, and to make bargain and sale of our rights, our possessions, and our common country. And we are constrained solemnly to declare, that we cannot but contemplate the enforcement of the stipulations of this instrument on us, against our consent, as an act of injustice and oppression, which, we are well persuaded, can never knowingly be countenanced by the Government and people of the United States; nor can we believe it to be the design of these honorable and highminded individuals, who stand at the head of the Govt., to bind a whole Nation, by the acts of a few unauthorized individuals. And, therefore, we, the parties to be affected by the result, appeal with confidence to the justice, the magnanimity, the compassion, of your honorable bodies, against the enforcement, on us, of the provisions of a compact, in the formation of which we have had no agency. Meyer Individuals and Society Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears Reading #3: A Soldier recalls the Trail of Tears 1. How did this man feel about the Cherokee people? What particular passages relay these emotions? 2. What was his opinion about the actions taken by the United States government? Use evidence from the text to support your answer. 3. Give two different examples of what Burnett did to try to ease the suffering of the Cherokee. 4. How did Burnett represent Andrew Jackson? Did he think Jackson behave honorably? Why or why not? A soldier recalls the Trail of Tears From “Birthday Story of Private John G. Burnett, Captain Abraham McClellan’s Company, 2nd Regiment, 2nd Brigade, Mounted Infantry, Cherokee Indian Removal, 1838–39.” (http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-newnation/4532) (edited for length) Children: This is my birthday, December 11, 1890, I am eighty years old today. I was born at Kings Iron Works in Sullivan County, Tennessee, December the 11th, 1810. I grew into manhood fishing in Beaver Creek and roaming through the forest hunting the deer and the wild boar and the timber wolf. … On these hunting trips I met and became acquainted with many of the Cherokee Indians, hunting with them by day and sleeping around their camp fires by night. I learned to speak their language, and they taught me the arts of trailing and building traps and snares. … The removal of Cherokee Indians from their life long homes in the year of 1838 found me a young man in the prime of life and a Private soldier in the American Army. Being acquainted with many of the Indians and able to fluently speak their language, I was sent as interpreter into the Smoky Mountain Country in May, 1838, and witnessed the execution of the most brutal order in the History of American Warfare. I saw the helpless Cherokee arrested and dragged from their homes, and driven at the bayonet point into the stockades. And in the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and fortyfive wagons and started toward the west. One can never forget the sadness and solemnity of that morning. Chief John Ross led in prayer and when the bugle sounded and the wagons started rolling many of the children rose to their feet and waved their little hands good-by to their mountain homes, knowing they were leaving them forever. Many of these helpless people did not have blankets and many of them had been driven from home barefooted. On the morning of November the 17th we encountered a terrific sleet and snow storm with freezing temperatures and from that day until we reached the end of the fateful journey on March the 26th, 1839, the sufferings of the Cherokee were awful. The trail of the exiles was a trail of death. They had to sleep in the wagons and on the ground without fire. And I have known as many as twenty-two of them to die in one night of pneumonia due to ill treatment, cold, and exposure. . . . I made the long journey to the west with the Cherokee and did all that a Private soldier could do to alleviate their sufferings. When on guard duty at night I have many times walked my beat in my blouse in order that some sick child might have the warmth of my overcoat. I was on guard duty the night Mrs. Ross died. When relieved at midnight I did not retire, but remained around the wagon out of sympathy for Chief Ross, and at daylight was detailed by Captain McClellan to assist in the burial like the other unfortunates who died on the way. … The long painful journey to the west ended March 26th, 1839, with four-thousand silent graves reaching from the foothills of the Smoky Mountains to what is known as Indian territory in the West. And covetousness on the part of the white race was the cause of all that the Cherokee had to suffer. . . . In the year 1828, a little Indian boy living on Ward creek had sold a gold nugget to a white trader, and that nugget sealed the doom of the Cherokee. In a short time the country was overrun with armed brigands claiming to be government agents, who paid no attention to the rights of the Indians who were the legal possessors of the country. Crimes were committed that were a disgrace to civilization. Men were shot in cold blood, lands were confiscated. Homes were burned and the inhabitants driven out by the gold-hungry brigands. Chief Junaluska was personally acquainted with President Andrew Jackson. Junaluska had taken 500 of the flower of his Cherokee scouts and helped Jackson to win the battle of the Horse Shoe, leaving 33 of them dead on the field. And in that battle Junaluska had drove his tomahawk through the skull of a Creek warrior, when the Creek had Jackson at his mercy. Chief John Ross sent Junaluska as an envoy to plead with President Jackson for protection for his people, but Jackson’s manner was cold and indifferent toward the rugged son of the forest who had saved his life. He met Junaluska, heard his plea but curtly said, “Sir, your audience is ended. There is nothing I can do for you.” The doom of the Cherokee was sealed. Washington, D.C., had decreed that they must be driven West and their lands given to the white man[. It is] the blackest chapter on the pages of American history.