Birthday Story of Private John G. Burnett, Captain Abraham

advertisement

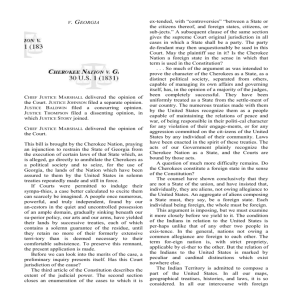

Birthday Story of Private John G. Burnett, Captain Abraham McClellan’s Company, 2nd Regiment, 2nd Brigade, Mounted Infantry, Cherokee Indian Removal, 1838–39. This letter tells the story of the Trail of Tears, as recalled by John G. Burnett, a soldier in the U.S. Army. Burnett had been friends with a number of the Cherokee but, as a soldier, had to help forcibly relocate them to Oklahoma in 1837–1838. The letter is written to his children on his eightieth birthday. "In the year 1828, a little Indian boy living on Ward creek had sold a gold nugget to a white trader, and that nugget sealed the doom of the Cherokees. In a short time the country was overrun with armed brigands [gangs] claiming to be government agents, who paid no attention to the rights of the Indians who were the legal possessors of the country. Crimes were committed that were a disgrace to civilization. Men were shot in cold blood, lands were confiscated. Homes were burned and the inhabitants driven out by the gold-hungry brigands. ... "The removal of Cherokee Indians from their life long homes in the year of 1838 found me a young man in the prime of life and a Private soldier in the American Army. Being acquainted with many of the Indians and able to fluently speak their language, I was sent as interpreter into the Smoky Mountain Country in May, 1838, and witnessed the execution of the most brutal order in the History of American Warfare. I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes, and driven at the bayonet point into the stockades [jail.] And in the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and forty-five wagons and started toward the west. "One can never forget the sadness and solemnity of that morning. Chief John Ross led in prayer and when the bugle sounded and the wagons started rolling many of the children rose to their feet and waved their little hands good-by to their mountain homes, knowing they were leaving them forever. Many of these helpless people did not have blankets and many of them had been driven from home barefooted." Source: North Carolina Digital History: http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchistnewnation/4532 From A Letter by Wilson Lumpkin To Eli S. Shorter, J.P.H. Campbell, and Alferd Iverson, Esqrs, May 4th, 1835 By 1835, having won his case for Indian removal in 1830 and with an ally in the White House in the person of Andrew Jackson, Governor Lumpkin of Georgia could call for a change in federal policy that offered protection for the remnants [remains] of the southeastern tribes. "I consider it a perfect farce [mockery] and degrading to the Government of the Union, under existing circumstances, to pretend any longer to consider or treat these unfortunate remnants of a once mighty race as independent nations of people, capable of entering into treaty stipulations[treaties] as such. These conquered and subdued remnants deserve the magnanimous [gracious] and liberal support and protection of the Government, and should be treated with tender regard, as orphans and minors who are incapable of managing and protecting their own patrimony [rights]. This course of policy, if pursued by the Federal Government, would soon relieve the States from the inquietudes [troubles] of an Indian population, and settle the Indians in a land of hope where they would be shielded and protected from the enormous and degrading frauds which have been so often perpetrated [committed] on these sons of the forest by an avaricious [greedy] and selfish portion of our white population....” Source: from Wilson Lumpkin, The Removal of the Cherokee Indians from Georgia, New York: Arno Press, 1969, pp 339-340 Sally M. Reece, Letter to Reverend Daniel Campbell, July 25, 1828 Missionaries preaching Christianity had been living among the Native American groups for decades. Originally employed by the US government on a mission to "civilize," the Natives, the results varied. Some missions focused solely on the conversion to Christianity, while others did include the teaching of Western culture, with or without the approval of the government. "First I will tell you about the Cherokees. I think they improve. They have a printing press and print a paper which is called the Cherokee Phoenix. They come to meeting on Sabbath days. They wear clothes which they made themselves. "Some though rude, have shoes and stockings. They keep horses, cows, sheep and swine. Some have oxen. They cultivate fields. They have yet a great many bad customs but I hope these things will soon be done away with. They have thought more about the Savior lately. I hope this nation will soon become civilized and enlightened." Source: The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents (Bedford Series in History and Culture) by Theda Perdue "We have unexpectedly become civilized" Cherokee Phoenix and Indians' Advocate vol. 1, no. 51 (Wednesday, March 4, 1829), p. 2 The Cherokee Phoenix was the national newspaper and an important tool in Native American resistance read not only by Native Americans, but also by American citizens and Europeans. "The Indians were represented as incapable of learning the arts of civilized life, and at the same time treated in most uncivil manner. They were savagely revengeful, because they had the spirit to resent the murder of their friends & relations. They were rogues and thieves, because, not knowing the method of legal processes to obtain justice, and if they did, their oath decreed to non-availing, they retaliated in the same way. They were drunkards, because intoxicating liquors were introduced among them. They were disinclined to the study of books, because of some few superficially educated under bad instruction had betrayed their countrymen and had set bad examples. They were stubborn, because they loved the land that had been endeared to them as an inheritance of their fathers. This flood of inconsistency [accusations] raged with violence over the heads of our Chiefs & swept with its waves, from under their feet, the earth, for which they had struggled for ages past. In this way our territory diminished, and our inheritance was circumscribed [limited] to its present bounds [boundaries]. "Our Chief displaced wonderful forbearance [patience] in this trials, and maintained the faith of treaties, with the United States, whose chief magistrate [judge] also exercised the spirit of paternal affection, and adhered to his engagements as pledged to us by treaties. With caution have we passed the strong shoals [winds] of opposition, and its mingled cruelties to the light of civilization. The sun has arise[n] in our moral horizon is fast advancing to its meridian [midpoint]. We hail it with joy! Although a part of our nation have detached themselves from us, to follow the chase, in the western wilds, and we are invited to retrograde [reverse] to savageism, with strong talks and inducements as bribes our appetite for our present enjoyments if is too strong to relinquish them because we have tasted their sweets and are contented." Source: North Carolina Digital History; http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchistnewnation/5234#comment-1780 from A Brief View of the Present Relations between the Government and People of the United States and the Indians within Our National Limits by Jeremiah Evarts, 1829 The American Board of Commissions for Foreign Missions was responsible for establishing most of the church missions and schools among the Cherokee and other southern tribes. Jeremiah Evarts was its leader and here provides arguments against the Indian Removal Act pending in Congress in 1829. "In the various discussions, which have attracted public attention within a few months past, several important positions, on the subject of the rights and claims of the Indians, have been clearly and firmly established. At least, this is considered to be the case, by a large portion of the intelligent and reflecting men in the community. Among the positions thus established are the following: 1. The American Indians, now living upon lands derived from their ancestors, and never alienated nor surrendered, have a perfect right to the continued and undisturbed possession of these lands. 2. Those Indian tribes and nations, which have remained under their own form of government, upon their own soil, and have never submitted themselves to the government of the whites, have a perfect right to retain their original form of government, or to alter it, according to their own views of convenience and propriety. 3. These rights of soil and of sovereignty are inherent in the Indians, till voluntarily surrendered by them; and cannot be taken away by compacts between communities of whites, to which compacts the Indians were not a party. 4. From the settlement of the English colonies in North America to the present day, the right of Indians to lands in their actual and peaceable possession, and to such form of government as they choose, has been admitted by the whites; though such admission is in no sense necessary to the perfect validity of the Indian title.... 9. By the constitution of the United States, the exclusive power of making treaties with the Indians was conferred on the general government; and, in the execution of this power, the faith of the nation has been many times pledged to the Cherokees, Creeks, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and other Indian nations. In nearly all these treaties, the national and territorial rights of the Indians are guaranteed to them, either expressly, or by implication. Treaty of New Echota, 1835 In December of 1835 a small group of Cherokee leaders including Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot negotiated a removal treaty with the United States. An overwhelming majority of the Cherokee disapproved of the treaty as evidenced in a petition presented by Chief John Ross to the United States Senate prior to its vote to approve. The Treaty of New Echota was ratified by a margin of one vote. Disapproval among the Cherokee resulted in the murder of John Ridge who had joined his father in signing the treaty. WHEREAS the Cherokees are anxious to make some arrangements with the Government of the United States whereby the difficulties they have experienced by a residence within the settled parts of the United States under the jurisdiction and laws of the State Governments may be terminated and adjusted; and with a view to reuniting their people in one body and securing a permanent home for themselves and their posterity in the country selected by their forefathers without the territorial limits of the State sovereignties, and where they can establish and enjoy a government of their choice and perpetuate such a state of society as may be most consonant with their views, habits and condition; and as may tend to their individual comfort and their advancement in civilization. And whereas the Cherokee people at their last October council at Red Clay, fully authorized and empowered a delegation or committee of twenty persons of their nation to enter into and conclude a treaty with the United States commissioner then present, at that place or elsewhere and as the people had good reason to believe that a treaty would then and there be made or at a subsequent council at New Echota which the commissioners it was well known and understood, were authorized and instructed to convene for said purpose.... ARTICLE 1. The Cherokee nation hereby cede relinquish and convey to the United States all the lands owned claimed or possessed by them east of the Mississippi river, and hereby release all their claims upon the United States for spoliations of every kind for and in consideration of the sum of five millions of dollars to be expended paid and invested in the manner stipulated and agreed upon in the following articles But as a question has arisen between the commissioners and the Cherokees whether the Senate in their resolution by which they advised “that a sum not exceeding five millions of dollars be paid to the Cherokee Indians for all their lands and possessions east of the Mississippi river” have included and made any allowance or consideration for claims for spoliations it is therefore agreed on the part of the United States that this question shall be again submitted to the Senate for their consideration and decision and if no allowance was made for spoliations that then an additional sum of three hundred thousand dollars be allowed for the same. from TREATY WITH THE CHEROKEE, 1835, as found at INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES, Oklahoma State University Library Electronic Publishing Center. Major Ridge, 1835 In December 1835, the U.S. resubmitted the treaty to a meeting of 300 to 500 Cherokees at New Echota. Older now, Major Ridge spoke of his reasons for supporting the treaty: "I am one of the native sons of these wild woods. I have hunted the deer and turkey here, more than fifty years. I have fought your battles, have defended your truth and honesty, and fair trading. The Georgians have shown a grasping spirit lately; they have extended their laws, to which we are unaccustomed, which harass our braves and make the children suffer and cry. I know the Indians have an older title than theirs. We obtained the land from the living God above. They got their title from the British. Yet they are strong and we are weak. We are few, they are many. We cannot remain here in safety and comfort. I know we love the graves of our fathers. We can never forget these homes, but an unbending, iron necessity tells us we must leave them. I would willingly die to preserve them, but any forcible effort to keep them will cost us our lands, our lives and the lives of our children. There is but one path of safety, one road to future existence as a Nation. That path is open before you. Make a treaty of cession. Give up these lands and go over beyond the great Father of Waters." Source: Thurman Wilkins, Cherokee Tragedy: The Story of the Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People (New York: Macmillan, 1970), 276-77; quoted in Ehle, Trail of Tears, 294. Catherine Beecher, Circular Addressed to the Benevolent Ladies of the U. States, December 29, 1829 Many women at the time regarded the treatment of the Cherokees and other Indians as immoral. The call to action came from Catherine Beecher, a prominent educator and writer, calling on women to petition Congress to defeat the Indian Removal Act. "The present crisis in the affairs of the Indian nations in the United States demands the immediate and interested attention of all who make claims to benevolence or humanity. The calamities now hanging over them threaten not only these relics of an interesting race, but, if there is a Being who avenges the wrongs of the oppressed, are causes of alarm to our whole country. "The following are the facts of the case:- This continent was once possessed only by the Indians and the earliest accounts represent them as a race numerous, warlike and powerful. When our forefathers sought refuge from oppression on these shores, this people supplied their necessities and ministered their comfort. .. "Ever since the existence of this nation, our general government, pursuing the course alike of policy and benevolence, have acknowledge these people as free and independent nations, and has protected them in the quiet possessions of their land... Our government also, with parental care, has persuaded the Indians to forsake their savage life, and to adopt the habits and pursuits of civilized nations, while the charities of Christian and the labours of missionaries have sent to them the blessings of the gospel to purify and enlighten.... "And where can be the harm of letting a few of our red neighbors, on a small remnant of their own territory, exercise the rights which God has given them? They have not the power to injure us; and, if we treat them kindly and justly, they will not have the disposition. They have not intruded upon our territory, nor encroached upon our rights. They ask only the privilege of living unmolested in the places where they were born, and in possession of those rights, which we have acknowledged and guaranteed. "May a gracious Providence avert from this country the awful calamity of exposing ourselves to the wrath of heaven, as a consequence of disregarding the cries of the poor and defenseless and perverting to purposes of cruelty and oppression, that power which was given us to promote the happiness of our fellow-men." Source: The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents (Bedford Series in History and Culture) by Theda Perdue Petition by ladies in Steubenville, OH, against Indian removal There were small pockets of opposition to the removal of Cherokees in Georgia and occasionally groups of people, such as the Quakers and an occasional abolitionist championed their rights. These women from Steubenville, Ohio used their only political right, the right of petition, to protest the Cherokee removal and to argue in favor of Native American natural rights. Their petition was ignored. MEMORIAL OF THE LADIES OF STEUBENVILLE, OHIO, Against the Forcible removal of the Indians without the limits of the United States FEBRUARY 15, 1830 To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States. The memorial of the undersigned, residents of the state of Ohio, and town of Steubenville, RESPECTFULLY SHEWETH: That your memorialists [petitioners] are deeply impressed with the belief, that the present crisis in the affairs of the Indian nations, calls loudly on all who can feel for the woes of humanity, to solicit, with earnestness, your honorable body to bestow on this subject, involving, as it does, the prosperity and happiness of more than fifty thousand of our fellow Christians, the immediate consideration demanded by its interesting nature and pressing importance. It is readily acknowledged, that the wise and venerated [respected] founders of our country's free institutions have committed the powers of Government to those whom nature and reason declare the best fitted to exercise them; and your memorialists would sincerely deprecate [frown upon] any interference on the part of their own sex with the ordinary political affairs of the country, as wholly unbecoming the character of the American females. Even in private life, we may not presume to direct the general conduct, or control the acts of those who stand in the near and guardian relations of husbands and brothers; yet all admit that there are times when duty and affection call on us to advise and persuade, as well as to cheer or console. And if we approach the public Representatives of our husbands and brothers, only in the humble character of suppliants [beggars] in the cause of mercy and humanity, may we not hope that even the small voice of female sympathy will be heard? When, therefore, injury and oppression threaten to crush a hapless [helpless] people within our borders, we, the feeblest of the feeble, appeal with confidence to those who should be representatives of national virtues as they are the depositaries of national powers[lawmakers] , and implore them to succor [help] the weak and unfortunate. In despite of the undoubted national right which the Indians have to the land of their forefathers, and in the face of solemn treaties, pledging the faith of the nation for their secure possession of those lands, it is intended, we are told, to force them from their native soil, to compel them to seek new homes in a distant and dreary wilderness. To you, then, as the constitutional protectors of the Indians within our territory, and as the peculiar guardians of our national character, and our counter's welfare, we solemnly and honestly appeal, to save this remnant of a much injured people from annihilation, to shield our country from the curses denounced on the cruel and ungrateful, and to shelter the American character from lasting dishonor. And your petitioners will ever pray. Lewis Cass, Removal of the Indians, January, 1830 Lewis Cass was the governor of the Michigan territory prior to statehood and dealt with Indians on the frontier. He was also a proponent of “Popular Sovereignty,” where each state should be allowed to decide its stance on slavery. THE destiny of the Indians, who inhabit the cultivated portions of the territory of the United States, or who occupy positions immediately upon their borders, has long been a subject of deep Solicitude [consideration] to the American government and people. Time, while it adds to the embarrassments and distress of this part of our population, adds also to the interest which their condition excites, and to the difficulties attending a satisfactory solution of the question of their eventual disposal [removal]. To the operation of the physical causes, which we have described, must be added the moral causes connected with their mode of life, and their peculiar opinions. Distress could not teach them providence, nor want industry. As animal food decreased, their vegetable productions were not increased. Their habits were stationary and unbending; never changing with the change of circumstances. How far the prospect around them, which to us appears so dreary, may have depressed and discouraged them, it is difficult to ascertain [determine,] as it is also to estimate the effect upon them of that superiority, which we have assumed and they have acknowledged. The cause of this total failure cannot be attributed to the nature of the experiment, nor to the character, qualifications, or conduct, of those who have directed it. But there seems to be some insurmountable [overwhelming] obstacle in the habits or temperament of the Indians, which has heretofore prevented, and yet prevents, the success of these labors. Whatever this may be, it appears to be confined to the tribes occupying this part of the continent. In Mexico and South America, a large portion of the aboriginal [native] race has accommodated itself to new circumstances, and forms a part of the same society with their conquerors. Impressed with the conviction, that a removal from their present position and from the vicinity [area near] of our settlements, to the regions beyond the Mississippi, can alone preserve from final extinction the remnant [last of] of our aboriginal [native] population, a number of benevolent men have associated themselves, and established a society under the appellation [name] of ‘The Indian Board, for the Emigration, Preservation, and Improvement of the Aborigines of America,’ The Indians would go, and go speedily and with satisfaction. A few perhaps might linger around the site of their council-fires; but almost as soon as the patents could he issued to redeem the pledge made to them, they, would dispose of their possessions and rejoin their countrymen. And even should these prefer ancient associations to future prospects, and finally melt away before our people and institutions, the result must be attributed to causes, which we can neither stay nor control. If a paternal authority is exercised over the aboriginal colonies and just principles of communication with them, and of intercommunication among them, are established and enforced, we may hope to see that improvement in their condition, for which we have so long and so vainly looked. Thomas Jefferson Excerpt from Letter to William Henry Harrison, 1803 Our system is to live in perpetual peace with the Indians, to cultivate an affectionate attachment from them, by everything just and liberal which we can do for them within the bounds of reason, and by giving them effectual protection against wrongs from our own people. The decrease of game rendering their subsistence by hunting insufficient, we wish to draw them to agriculture, to spinning and weaving. When they withdraw themselves to the culture of a small piece of land, they will perceive how useless to them are their extensive forests, and will be willing to pare them off from time to time in exchange for necessaries for their farms and families. As to their fear, we presume that our strength and their weakness is now so visible that they must see we have only to shut our hand to crush them, and that all our liberalities to them proceed from motives of pure humanity only. Should any tribe be fool-hardy enough to take up the hatchet at any time, the seizing the whole country of that tribe, and driving them across the Mississippi, as the only condition of peace, would be an example to others, and a furtherance of our final consolidation. Source: Contending Voices. John Hollitz and A. James Fuller. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. Tecumseh, Excerpt from Speech in 1811– “Sleep Not Longer, O Choctaws and Chicasaws” Have we not courage enough remaining to defend our country and maintain our ancient independence? Will we calmly suffer the white intruders and tyrants to enslave us? The annihilation of our race is at hand unless we unite in one common cause against the common foe. Think not, brave Choctaws and Chicasaws, that you can remain passive and indifferent to the common danger, and thus escape the common fate. Your people, too, will soon be as falling leaves and scattering clouds before their blighting breath. You, too, will be driven away from your native land and ancient domains as leaves are driven before the wintry storms. Before the palefaces came among us, we enjoyed the happiness of unbounded freedom, and were acquainted with neither riches, wants nor oppression. How is it now? Wants and oppression are our lot; for are we not controlled in everything? Are we not being stripped day by day of the little that remains of our ancient liberty? Do they not even kick and strike us as they do their black-faces? How long will it be before they will tie us to a post and whip us, and make us work for them in their cornfields as they do them? Shall we wait for that moment or shall we die fighting before submitting to such ignominy? The white usurpation in our common country must be stopped, or we, its rightful owners, be forever destroyed and wiped out as a race of people. I am now at the head of many warriors backed by the strong arm of English soldiers. Choctaws and Chickasaws, you have too long borne with grievous usurpation inflicted by the arrogant Americans. Source: Contending Voices. John Hollitz and A. James Fuller. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. Excerpt from Indian Removal Act 1830 An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That it shall and may be lawful for the President of the United States to cause so much of any territory belonging to the United States, west of the river Mississippi, ... as he may judge necessary, to be divided into a suitable number of districts, for the reception of such tribes or nations of Indians as may choose to exchange the lands where they now reside... And be it further enacted, That in the making of any such exchange or exchanges, it shall and may be lawful for the President solemnly to assure the tribe or nation with which the exchange is made, that the United States will forever secure and guaranty to them, and their heirs or successors, the country so exchanged with them;... And be it further enacted, That upon the making of any such exchange as is contemplated by this act, it shall and may be lawful for the President to cause such aid and assistance to be furnished to the emigrants as may be necessary and proper to enable them to remove to, and settle in, the country for which they may have exchanged; and also, to give them such aid and assistance as may be necessary for their support and subsistence for the first year after their removal. And be it further enacted, That it shall and may be lawful for the President to cause such tribe or nation to be protected, at their new residence, against all interruption or disturbance from any other tribe or nation of Indians, or from any other person or persons whatever... And be it further enacted, That for the purpose of giving effect to the Provisions of this act, the sum of five hundred thousand dollars is hereby appropriated, to be paid out of any money in the treasury, not otherwise appropriated. Chief Justice John Marshall Excerpt from Worcester v. Georgia The Cherokee nation...is a distinct community, occupying its own territories, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter. Source; Printed with the permission of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History Excerpt from Memorial and Protest of the Cherokee Nation, 1836 The Cherokees were happy and prosperous under a scrupulous observance of treaty stipulations by the government of the United States, and from the fostering hand extended over them, they made rapid advances in civilization, morals, and in the arts and sciences. Little did they anticipate, that when taught to think and feel as the American citizen, and to have with him a common interest, they were to be despoiled by their guardian, to become strangers and wanderers in the land of their fathers, forced to return to the savage life, and to seek a new home in the wilds of the far west, and that without their consent. We wish to remain on the land of our fathers. We have a perfect and original right to remain without interruption or molestation. The treaties with us, and laws of the United States made in pursuance of treaties, guaranty our residence and our privileges, and secure us against intruders. Source; Printed with the permission of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History