Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions

advertisement

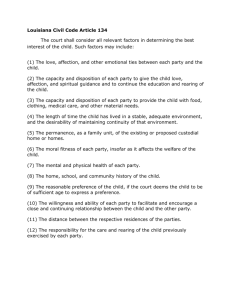

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyright material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction not be "used for any purposes other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. Chapter 13 SOCIAL DESIRABILITY IN CROSSCULTURAL RESEARCH TIMOTHY P. JOHNSON AND FONS J. R. VAN DE VIJVER 13.1 mSTORY The concept of social desirability derives its origin, more than 50 years ago, from a common observation by interviewers that what respondents say may not be true or not entirely true. The given answer is asswned to show a consistent distortion from reality: respondents portray themselves too positively. Scales were developed to assess this tendency, with the aim of designing measures that could indicate the level of veridicality of answers on other items. The Lie Scale of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire and the Marlowe~Crowne Scale (discussed below) are examples of this line of thinking. Later research, however, has provided important extensions: some items are more susceptIble than others to trigger socially desirable answers; also, some individnals are more likely to show socially desirable behavior than others. The consistency of individual differences in social desirability has led some theoreticians to argue that social desirability is not a response style but a personality characteristic related to conformism. Both views (social desirability as a response style versus social desirability as a stable personality characteristic) are described in this chapter. It may not be superfluous to remark that these two views, at times, hardly seem compatible and refer to seemingly unrelated research traditions. Current cognitive models have largely failed to address the potential role of culture in evaluating target opinions and behaviors as being socially desirable, undesirable or neutral, as well as in the decision as to whether or not undesirable responses will be modified to conform to perceived norms. In this chapter, we evaluate social desirability as a source 'of survey measurement error and explore its implications for the conduct of cross~cultural research. Our focus is not on exploring how social desirability can affect answers but on determining whether social desirability has a differential impact on respondents from different cultural backgrounds. We argue in the present chapter that in some cases in cross-cultural survey research, the view of social desirability as a screen put in front of interviewers to prevent their view of the respondent's reality is useful, while in other studies constructs are examined that are so closely related to social desirability that any correction for it would decrease the validity of cross-cultural comparisons. 193 194 13.2 Part III SOCIAL DESIRABILITY AS RESPONSE STYLE Cognitive models of survey infonnation processing that have been developed over the past 20 years generally consider a four-stage process by which respondents answer survey questions (Sudman, Bradburn, and Schwarz 1996). During the first three stages, respondents interpret questions, search for relevant infonnation in semantic memory, and form answers. It is now understood that various sources of measurement error may be introduced at each of these stages. For example, questions may be misunderstood, respondents may be unable to retrieve necessary infonnation, and responses may be incorrectly mapped onto survey response scales. Although serious, these are generally viewed as unintentional forms of measurement error. We contrast these with the fourth stage, during which true survey answers (or what the respondent believes to be true) are evaluated and sometimes edited (whether deliberately or not) for social desirability prior to reporting. We define social desirability in the response-style view as the tendency ofindividuals to "manage" social interactions by projecting favorable images of themselves, thereby maximizing conformity to others and minimizing the danger of receiving negative evaluations from them. Concerns regarding the effects of social desirability on survey data quality led to the development of several measures designed to assess it. The developers of these measures conceptualized the tendency to provide socially desirable reports as a personality trait; some survey respondents might thus be more vulnerable to social desirability influences than others. Among U.S. researchers, one of the most commonly employed measures has been the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability, or Need for Approval, Scale (Crowne and Marlowe 1960, 1964). A meta-analysis reported that over 90% of the available research literature that has employed a social desirability measure used the Marlowe-Crowne (MC) Scale (Moonnan and Podsakoff 1992). Each of the 33 true-false items describe either culturally acceptable but improbable or culturally unacceptable but probable behaviors. Consistent with theoretical expectations, the MC Scale has been found to be inversely correlated with self-reports of numerous behaviors and conditions generally believed to be socially undesirable, including symptoms of psychiatric illness or distress, suicidal thoughts, and drug and alcohol use (Klassen et a1. 1975; Carr and Krause 1978; Strosahl et a1. 1984; Welte and Russell 1993; Watten 1996). It is also found to be positively correlated with socially-desirable self-evaluations, such as degree of life satisfaction and happiness (Carstensen and Cone 1983; Kozma and Stones 1987). The MC measure has also been consistently shown to have moderate correlations with other social desirability scales, including the Edwards social desirability scale (range 0.32.042; Crino et a1. 1983; Strosahl et a!. 1984; Kozma and Stones 1987) and the Eysenck Lie Scale (range 0.45-0.55, McCrae and Costa 1983; Khavari and Mabry 1985). This latter measure, more formally known as the Lie Scale of the Eysenck Personality Inventory (Eysenck and Eysenck 1964), is commonly employed in countries other than the United States. SOCIAL DESIRABILITY IN CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH 13.3 195 SOCIAL DESIRABILITY AS SUBSTANCE The interpretation of negative correlations between social desirability measures and various symptoms and behaviors as evidence of mere response artifacts has been challenged. Bradburn, Sudman (1979b), for example, have interpreted the negative findings as evidence that persons who score high on tests of social desirability do, in fact, behave in an altruistic manner consistent with the underlying personality trait represented by these measures. Welte and Russell (1992) have put forth a similar argument. Empirical support for this position comes from a study that employed an external criterion. McCrae and Costa (1983) demonstrated that persons with high Marlowe-Crowne and Eysenck Lie scores were, in fact, rated more positively by their spouse across a variety of psychosocial measures. In addition, adjustments for social desirability using the MC Scale in order to get a more valid picture of the relationship between two target measures have been unsuccessful (Campbell, Converse, and Rodgers 1976; Gove et al. 1976; Gove and Geerken 1977; Kozma and Stones 1987; Welte and Russell 1993). In other instances, controlling for scores on the MC Scale has actually decreased validity coefficients (McCrae 1986). Similar findings have been reported when attempting to correct for social desirability using the Eysenck Lie Scale (McCrae and Costa 1983). 13.4 CROSS-CULTURAL STUDIES OF SOCIAL DESIRABILITY 13.4.1 Social Desirability as a Person Characteristic Early on in the conceptualization of social desirability, there was recognition that culture was important in classifYing opinions and behaviors as desirable or not. Crowne and Marlowe (1964) suggested that socially desirable responding was motivated by "the need of subjects to respond in culturally sanctioned ways" in order to obtain social approval. Yet, cultural variation in social desirability and the possible impact 0 f differential social desirability 0 n cross-cultural surveys have never been seriously examined. We know from cross-cultural work that there are both universals and cultural specifics in social behavior. Some norms that have obvious implications for survey behavior, such as the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner 1960), are important to many cultures and might at an abstract level approach classification as etic, or pancultural. Yet, there are broad cross-cultural differences in specific beliefs regarding for whom, where and when reciprocity is appropriate, suggesting that the practice of reciprocity is at least in part unique, or ernic, within each culture. Survey questions that do not activate cultural perceptions of desirability or undesirability will likely be processed and answered without deliberate misrepresentation. Culturally filtered social desirability perceptions alone, however, are not sufficient to trigger response editing. Cultural norms may also dictate those situations in which it is and is not necessary or appropriate to mislead others. Within collectivist societies, for example, the restrictions against providing misleading 196 Partm information to members of external groups are generally weaker than within individualist societies (Triandis 1995). Consequently, a survey question may be interpreted as having similar levels of socially desirable content by respondents from varying cultural groups, yet persons from one cultural background may be more likely to edit their responses than those from another. This suggests that culture's influence on social desirability involves a two-step process. F or any given survey question, respondents will interpret, based on their cultural experiences, whether or not it contains socially desirable or undesirable content. Among those who do perceive it as containing such content, some will then determine (also based on cultural experience) that the question should nonetheless be answered as accurately as possible, while others will decide that response editing to conform with social norms is necessary and/or appropriate. Recent work that highlights cultural variations in perceptions of the appropriateness of lying in various social contexts is consistent with this process (Fu et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2001). Warnecke et al. (1997) reported findings from Chicago, illinois indicating that both African A merican a nd Mexican American (but not Puerto Rican) respondents had higher MC scores than non-Hispanic Whites after controlling for gender, age, education, and income. Several other U.S. studies and one from South Africa have also documented higher social desirability scores, using both the MC and similar measures, among Black, when compared to White, respondents (Crandall and Crandall 1965; Fisher 1967; Klassen et al. 1975; Edwards and Riordan 1994). Recent data has also documented higher MC scores among East Asians, compared to U.S.born, subjects (Middleton and Jones 2000; Keillor et al. 2001). In a comparison of European Americans, Mexican Americans, and Mexicans, Ross and Mirowsky (1984) also found substantial cultural differences in social desirability as measured by the MC Scale. The authors reported that Mexican Americans revealed higher social desirability scores than did European Americans and Mexicans. They attributed the intergroup differences to the relative power of these groups in society. Groups with low power, as often is the case with immigrant groups, tend to be more concerned with impression management and hence display more socially desirable behavior. Differences in social power are an equally plausible explanation for BlackWhite variability in MC scores. Other comparisons of MC scores across racial and ethnic groups, however, have provided counter-intuitive (Abe and Zane 1999) or nodifference findings (Tsushima 1969; Gove and Geerken 1977; Welte and Russell 1993; Okazaki 2000). ,_ In one of the few cross-cultural studies of social desirability, Johnson et at. (1997) reported findings from a series of cognitive interviews with samples of adults representing four distinct cultural groups in Chicago: African American, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and non-Hispanic White. When asked if they believed that people in general would over- or underreport behaviors that appeared to vary in their degree of social desirability (e.g., the frequency of consuming fruits/vegetables and alcohol), no cross-group differences were found. A national survey in the United States also failed to find differences in the perceived social desirability 0 f s ets 0 f psychiatric, self-esteem and positive affect descriptors (Gove and Geerken 1977). In SOCIAL DESIRABILITY IN CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH 197 one available cross-national study, American, French and Italian judges also showed high correlations of greater than 0.80 in their evaluations of the desirability of items included in the Adjective Check List (Gough and Heilbrun 1980). In the United States, several researchers have documented a strong relationship between individual judgments of the desirability of personality traits and the probability that they will endorse questions about each (Edwards 1953; Philips and Clancy 1970). Dohrenwend (1966) found this p attem to be consistent a cross four ethnic groups residing in New York City. Comparative data from other nations also confirm that social desirability perceptions influence behavior in a similar manner across varied cultural groups. Tiirk Smith et al. (1993) reported high correlations between these variables among both Turkish and American students (0.86 and 0.87, respectively). In another study, Gendre and Gough (1982, quoted in TUrk Smith et al. 1993) administered the Adjective Check List to Italian and French subjects. This list consisted of3 00 person-descriptive adjectives, such a s clever a nd fickle. S ubj ects were asked to rate both the applicability of the adjective to themselves and the social desirability of each behavior. A high correlation was found within both cultural groups. In Japan, lower but still significant correlations were also reported (lwawaki, Fukuhara, and Hidano 1966) between these same measures. In a more recent study, Williams, Satterwhite, and Saiz (1998) asked students in ten countries (Chile, China, Korea, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Portugal, Singapore, Turkey, and the United States) to rate the favorability of each of the items from the Adjective Check List. Favorability can be taken to be closely related to social desirability. The average cross-country correlation was 0.82. The authors also computed the correlation between the average item scores for female and male students; the mean correlation across the ten countries was 0.97. The study illustrates that cross-cultural similarities in judgments of social desirability appear to outweigh cross-cultural differences. Yet, the drop from 0.97 to 0.82 cannot be accounted for by attenuation; there appears to be a large core of cross-culturally shared views on the (un)favorability of person descriptors but there are also country-specific aspects that must be considered. In general, the findings from these studies suggest that social desirability is likely to be a universal concept, given the strong cross-cultural similarities in ratings of social desirability and associated reporting behaviors across cultures. That some differences in patterning across countries were also found, though, suggests the possible presence of culture-specific factolS. Some studies have examined constructs that are closely related to social desirability, such as individualism-collectivism, expressiveness, and self-disclosure. According to Triandis (1995), honesty in interactions with strangers is a characteristic that is more highly valued in individualist societies, while concern about maintaining good relationships and face-saving are more salient (and hence, socially desirable) in collectivist countries. Johnson (1998) has reported findings from a study in the United States that documented a positive correlation between the Mar10we-Crowne and a collectivist orientation scale (0.20) and a negative correlation between the Marlowe-Crowne and a measure of individualism (-0.19). In a review of 198 Part ill studies on cross-cultural differences in connnunication styles, Smith and Bond (1998) discuss studies of self-disclosure. With remarkable consistency, members of individualist societies are found to be more inclined to reveal information about themselves both to members of their in-group as well as to out-group representatives, while members of collectivist societies often make a sharp distinction between ingroup and out-group members and show less disclosure towards the latter. Other research has compared social desirability indices across cultural groups at the macro leveL A large database on cross-national differences in social desirability can be derived from work with Eysenck's Lie Scale. This instrument, translated into various languages, has been used in well over 300 studies, covering more than 40 countries. Van Hemert et al. (2001) examined the relationship between Lie Scale scores and the Gross National Product of various countries. Based on data for 38 countries, they found a highly significant, negative correlation of -0.67, with more affiuent countries tending to show lower social desirability scores. We note here that economic a ffiuence is a Iso positively associated with individualism at the national level (Hofstede 2001). It can be concluded that, if conceptualized as a person characteristic, there are important cross-cultural differences in social desirability. Persons coming from more influential groups in society or from more affiuent countries tend to show lower scores on social desirability. In the previous section it was found that cultures do not seem to differ greatly in what is seen as desirable behavior. A combination of these results leads us to conclude that social desirability is an important source of crosscultural score differences and that it can be fairly adequately measured in a crosscultural framework. The psychological meaning is less clear-cut; there is some disagreement in the literature as to whether social desirability is "mere response editing" or is associated with various other psychological traits, such as agreeableness and need for affiliation. Yet, even within the latter view, it is important to take the role of social desirability into account in cross-cultural studies, as it constitutes an important source of score differences. It is probably the most common alternative explanation of country differences in survey research and deserves to be treated accordingly (e.g., by administering a measure of social desirability). 13.4.2 Social Desirability as a Question Characteristic A contrasting perspective that dates back several decades argues that social desirability is more properly viewed as due to question characteristics or the survey interaction process between interviewer and interviewee (phillips and Clancy 1972; DeMaio 1984). In general, this approach is concemed with identifying question types and other elements of the survey context that are most likely to elicit socially desirable, but incorrect, responses. Here, we briefly review contextual evidence of cross-cultural differences in socially desirable responding. Consistent with some findings from comparisons of social desirability scales across ethnic groups, available evidence also suggests greater misreporting of socially desirable behavior among SOCIAL DESIRABrr.ITY IN CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH 199 minority groups in the United States In particular, validation studies have consistently documented more overreporting of voter participation among nonwhite groups when compared with Whites (Katosh and Traugott 1981; Abramson and Claggett 1986). Similar validation studies have also shown that U.S. minorities may underreport socially stigmatizing behaviors such as substance use and abortions to a greater degree than the majority White population (Jones and Forrest 1992; Hser 1997). Some of the most compelling evidence regarding the effects of culture on the survey process comes from studies that have demonstrated that cultural distance between respondents and interviewers sometimes produces varying patterns of responses. In U.S. studies, respondents have been shown to defer to the perceived values of other-race interviewers when answering relevant survey questions (Cotter et al. 1982; Anderson et al. 1988; Finkel, Guterbock, and Borg 1991; Davis 1997). However, one experimental study that manipulated the expressed nationality of Oriental interviewers as South Vietnamese, Thai, or Japanese, found that the effects on student opinions regarding the Vietnam War might not always be in the predicted direction (Hue and Sager 1975). Another U.S. study that conducted cognitive interviews with respondents from four cultural groups probed about their comfort discussing alcohol consumption with interviewers from their own and other race/ethnic groups (Johnson et al. 1997). They found non-Hispanic Whites were equally comfortable with the idea of discussing their alcohol consumption with interviewers of their own vs. other cultural groups. Minority group respondents (African American, Mexican American, and Puerto Rican), in contrast, expressed less comfort discussing the topic with interviewers from other cultural groups. These findings were interpreted within an individuaIist-collectivist framework that would expect representatives of individualist cultures to be equally comfortable discussing sensitive information with interviewers from their own and other cultures. In contrast, respondents from more collectivist cultures may be expected to have greater difficulty discussing sensitive topics with interviewers from different cultural groups. Cultural differences in the effects of interview mode 0 n self-reports 0 f sensitive survey questions have also been examined. Aquilino (1994) examined the influence of mode of survey administration on answers to questions dealing with the use of psychotropic substances, including alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine a cross cultural groups in the United States face-ta-face and telephone interviews and selfadministered questionnaires were administered to non-Hispanic White, Black, and Hispanic respondents. Mode effects were smaller for non-Hispanic Whites than for minority group members, who were more likely to report lower levels of substance use when interviewed, compared to when completing self-administered questionnaires. Similar findings have been reported by Park et al. (1988), who found lower reporting of physical and mental health symptoms in self-administered questionnaires, compared to personal interviews, among foreign-born Koreans in the United States In contrast, no differences in reporting were found by data collection mode among U.S.-born Whites and Japanese Americans. These findings suggest that privacy is an important consideration among respondents when deciding whether or not they are willing to report socially unpopular opinions. It also indicates that the Partm 200 need for privacy may be variable across cultural groups when discussing sensitive topics such as illicit drug use and mental health. Why might this be so? Drug use reporting is a good example to explore in this regard. When validated against biochemical measures of drug ingestion, systematic differences in the accuracy of the substance use behaviors reported by African American vs. White respondents in the United States have been observed. These differences have been found when using a variety of validation methodologies, including comparisons with urine, saliva, and hair specimens (Page et a1. 1977; Hser 1997; Fendrich et a1. 1999). Findings have generally suggested that the reports provided by African American respondents are less accurate. How might social desirability account for this differential in survey response quality? It is commonly recognized that African Americans in the United States have for centuries experienced severe racial discrimination. Subsequent to slavery, African Americans were also exploited in the name of medical research. Most well known is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which a sample of African American males with this condition were studied, but remained untreated for nearly 40 years (Jones 1981). In addition, rumors of medical exploitation, including kidnapping and grave robbing to obtain medical school cadavers (Humphrey 1973), and of eugenic attempts to sterilize African Americans (Darity and Turner 1972), and more recently, the development of the AIDS virus as a weapon to be used against African Americans (Stevenson 1994), are not uncommon. African Americans are also known to be treated more harshly than Whites by the U.S. criminal justice system (Sampson and Lauritsen 1997). Consequent beliefs about group exploitation and unfair treatment by law enforcement officials are likely to create strong pressures to avoid reporting socially sanctioned behaviors. In the United States, there are currently few behaviors more stigmatizing than drug use. African Americans are thus likely to require greater privacy assurances and protections when asked to accurately report highly sensitive drug use behaviors. Greater privacy demands are also likely to be found among vulnerable minority groups in other social contexts when asked to report socially undesirable behaviors. In general, the empirical record clearly shows that social desirability can result from question and administration characteristics, especially when questioning socially sensitive issues. The relevance and potentially disturbing role of social desirability is compounded when the different cultures studied have different views on the acceptability o(particular behaviors such as abortion, and condom or drug use. 13.5 CONCLUSIONS In much of the literature we have reviewed, social desirability is treated as a person characteristic. Particularly the early literature treats social desirability as a nuisance variable that can distort the view on the social reality. In more recent literature, there is a growing appreciation of the limitations of this view. That there is a strong SOCIAL DESIRABILITY IN CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH 201 correlation between the perceived desirability of a psychological trait or behavior and the likelihood that a person is willing to acknowledge that trait or behavior (Edwards 1953) cannot be dismissed as a methodological artifact; it reveals important information about the social reality of the respondent. However, social desirability appears to be a combination of style and substance; some even maintain that there is more substance than style in social desirability (McCrae and Costa 1983). Attempts to tease out the two aspects are unlikely to enhance our understanding. Similarly, it is fruitless to treat social desirability only as a person or a survey item characteristic. The two are better seen as two sides of the same coin: social desirability is a personality characteristic with an influence on what a respondent wants to transpire in a survey. Like other personality characteristics, it is manifested more in some situations than in others; social desirability is more likely to affect measurement when dealing with sensitive issues or with less anonymous modes of data collection. The cross-cultural studies of personality measures of social desirability are not numerous, but are remarkably convergent in findings: social desirability shows systematic cross-cultural differences. These differences are negatively related to the level of affluence of the countries, and to the level of social power of the individuals involved. Individuals from more affluent countries tend on average to show lower social desirability scores. Although it is not yet clear which factors produce cultural differences in social desirability, a picture seems to be slowly emerging. One finding is the strong relationship between GNP and social desirability. From a substantive view, GNP ism erely a s unnnary I abel for a host of underlying variables, such as national differences in level of education and personal income. It is unlikely that cross-cultural differences in social desirability can be accounted for by schooling. At the individual level, Warnecke et al. (1997) found that even after controlling for education and income, African and Mexican Americans revealed higher levels of social desirability than did non-Hispanic Whites. Cross-national differences in social desirability may, however, be related to cultural value systems such as the individualism and collectivism dimensions. As discussed earlier, some evidence from individual-level research suggests that social desirability scores may be higher in collectivistic societies (Johnson 1998b). In line with this fmding, Van Hernert et al. (1999) reported in a sample of 23 countries a significant correlation of -0.68 between a country's individualism score and its score on Eysenck's Lie Scale. These observations are consistent with other evidence from case studies of collectivistic-societies that suggest that cultural emphasis on certain modes of social interaction, such as simpatia in Latino cultures (Triandis et al. 1984) and the "courtesy bias" in traditional Asian cultures (Jones 1983), may encourage the production of socially desirable information during survey interviews as a byproduct of respondent need to maintain positive and harmonious relations with their interviewer. Consistent with these findings, a meta-analysis conducted by Bond and Smith (1996) found a significant relationship between a measure of conformity (in the so-called Asch paradigm) of a country and its level of collectivism Much of the empirical evidence on intra- and cross-national differences in social desirability 202 Part III discussed here suggests that the need for affiliation, confonnity, approval, and (lack of) self-disclosure are psychological constructs closely related to social desirability. Despite the theoretical ambiguity of the construct of social desirability (as either related to lying or the need for confonnity), the practical ramifications are clear; depending on the topic of study, social desirability can lead to various distortions of cross-cultural comparisons. A researcher comparing abortion rates across countries may face social desirability as a major obstacle: women may deliberately lie and the degree oflying may differ, depending on, among other things, the legality of abortion in the country. In this study the classical view of social desirability as a response style will be more helpful than its alternative, and measures such as randomized response techniques may be needed to correct for this social desirability. In other cases, however, measures to correct for social desirability may reduce the validity of the cross-cultural comparison; this holds for constructs that are related to confonnity, face management, and deference. Social desirability is also related to the cultural distance of the groups studied. If social desirability affects all items of a scale and the countries compared are widely different (e.g., in terms of affluence), there is a fair chance that observed score differences are due, at least in part, to social desirability rather than to the construct of the scale. The need to correct for social desirability may also depend on its expected size. If social desirability affects only a few items, item bias techniques may identify the anomalous items. In sum, there is no simple safeguard against social desirability; however, depending on factors such as cultural distance and topic of study, it is often possible to evaluate whether there is reason to be cautious in interpreting the cross-cultural differences or even a score correction or whether such . a correction would be countereffective. Much cross-cultural research on attitudes and beliefs seems to be implicitly geared towards the observation of significant differences. It is remarkable that cross-cultural differences in the social-psychological domain are often taken for granted, whereas cross-cultural score differences in the cognitive domain are often "explained away" by referring to measurement artifacts (cf. Van de Vijver and Leung 1997). The recognition of the impact of social desirability would be an important first step towards the establishment of an impartial treatment of cross-cultural differences. Development of theories that explain cultural differences in social desirability tendencies and methods that can measure and control for them during the conduct of cross-cultural survey re~~arch are an important challenge for future work. SOCIAL DESIRABILITY IN CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH 203 References Abe, J, and Zane, NWS (1990) Psychological maladjustment among Asian and White American college students: Controlling for confounds. Journal of Counseling Psychology 37: 437-444. Abramson, PR and Claggett, W (1986) Race-related differences in selfreported and validated turnout in 1984. Journal of Politics 48: 412-422. Anderson, BA, Silver, BD and Abramson, PR (1988) The effect of race of the interviewer on race-related attitudes of black respondents in SRC/CPS national election studies. Public Opinion Quarterly 52: 289-324. Aquilino, WS (1994) Interviewer mode effects in surveys of drug and alcohol use. Public Opinion Quarterly 58: 210-240. Bond, R and Smith, PB (1996) Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch's (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin 119: 111-137. Bradburn, NM, Sudman, S and Associates (1979) Reinterpreting the Marlowe-Crown scale. pp. 85-106 in NM Bradburn, S Sudman and Associates, Improving Interview Method and Questionnaire Design. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Campbell, A, Converse, PE and Rodgers, WL (1976) The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations, and Satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Carr, LG and Krause, N (1978) Social status, psychiatric symptomatology, and response bias. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19:86-91. Carstensen, LL andeone, JD (1983) Social desirability and the measurement of psychological well-being in elderly persons. Journal of Personality 38:713-715. Cicourel, AV (1964) Method and Measurement in Sociology. New York: Free Press. Cotter, PR, Cohen, J and Coulter, PB (1982) Race-of-interviewer effects in telephone interviews. Public Opinion Quarterly 46: 278-284. 204 PartIn Crandall, VC and Crandall, VJ (1965) A children's social desirability questionnaire. Journal of Consulting Psychology 29:27-36. Crino, MD, Svoboda, M, Rubenfield, S and White, MC (1983) Data on the Marlowe-Crowne and Edwards social desirability scales. Psychological Reports 53:963-968. Crowne, DP and Marlowe, D (1960) A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology 24:349-354. Crowne, DP and Marlowe, D (1964) The Approval Motive. New York: Wiley. Darity, W A and Turner, CB (1972) Family planning, race consciousness and the fear of genocide. American Journal of Public Health 62: 14541459. Davis, DW (1997) Nonrandom measurement error and race of interviewer effects among African Americans. Public Opinion Quarterly 61: 183-207. DeMaio (1984) Social desirability and survey measurement: A review. pp. 257-281 in C Turner (Ed.) Surveying Subjective Phenomena. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Dohrrenwend, B (1966) Social status and psychological disorder: An issue of substance and an issue of method. American Sociological Review 31: 14-34. Edwards, AL (1953) The relationship between the judged desirability of a trait and the probability that the trait will be endorsed. Journal of Applied Psychology 37:90-93. Edwards, D and Riordan, S (1994) Learned resourcefulness in Black and White South African university students. Journal of Social Psychology 134: 665-675. Eysenck, HJ and Eysenck, SBG (1964) Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory. London: University Press. SOCIAL DESIRABILITY IN CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH 205 Fendrich, M, Johnson, TP, Sudman, S, Wislar, J Sand Spiehler, V (1999) Validity of drug use reporting in a high-risk community sample: A comparison of cocaine and heroin survey reports with hair tests. American Journal of Epidemiology 149: 955-962. Finkel, SE, Guterbock, TM and Borg, MJ (1991) Race-of-interviewer effects in a presidential poll: Virginia 1989. Public Opinion Quarterly 55: 313-330. Fioravanti, M, Gough, HG and Frere, LJ (1981) English, French, and Italian adjective check lists: A social desirability analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 12: 461472. Fisher, G (1967) The performance of male prisoners on the MarloweCrowne social desirability scale: II. Differences as a function of race and crime. Journal of Clinical Psychology 23:473475. Gendre, F and Gough, HG (1982) Note cemant les pourcentages de responses a l' Adjective Check List de H. Gough pour des echantillons Francais et Americains. [Note concerning the percentages of responses to the Adjective Check List ofH. Gough for French and American samples]. Revue de Psychologie Appliquee 32: 81-90. Gough, HG and Heilbrun, AB Jr. (1980). The Adjective Check List manual. Palo Alto, CA: ConSUlting Psychologists Press. Gouldner, A (1960) The norm of reciprocity. American Sociological Review 25: 161-179. Gove, WR and Geerken, MR (1977) Response bias in surveys of mental health: An empiricaJJnvestigation. American Journal of Sociology 82:1289-1317. Gove, WR, McCorkel, J, Fain, T and Hughes, MD (1976) Response bias in community surveys of mental health: Systematic bias or random noise? Social Science & Medicine 10:497-502. Hofstede, G. (1984) Culture's Consequences, Abridged Edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage 206 Part III Hser, YI (1997) Self-reported drug use: Results of selected empirical investigations of validity. pp. 320-343 in L Harrison and A Hughes (Eds.) The Validity of Self-Reported Drug Use: Improving the accuracy of survey estimates. NIDA Research Monograph 167. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Hue, PT and Sager, EB (1975) Interviewer's nationality and outcome of the survey. Perceptual and Motor Skills 40: 907-913. Humphrey, DC (1973) Dissection and discrimination: The social origins of cadavers in Aplerica, 1760-1915. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 49: 819-827. Iwawaki, S, Fukuhara, M and Hidano, T (1966) Probability of endorsement of items in the Yatabe-Guilford Personality Inventory: Replication. Psychological Reports 19: 249-250. Johnson, TP (1998) Empirical evidence of an association between individualisrnlcollectivism and the trait social desimbility." Paper presented at the Third ZUMA Symposium on Cross-Cultural Survey Methodology, Leinsweiler, Germany. Johnson, TP, O'Rourke, D, Chavez, N, Sudman, S, Warnecke, R, Lacey, L and Horm, J (1997) Social cognition and responses to survey questions among cultumlly diverse populations. pp. 87-113 in L Lyberg, P Biemer, M Collins, E de Leeuuw, C Dippo, N Schwarz and D Trewin (Eds.) Survey Measurement and Process Quality. New York: john Wiley & Sons. Jones, EL (1983) The courtesy bias in South-East Asian surveys. pp. 253260 in M Bulmer and DP Warwick (Eds.) Social Research in Developing Countries. London: UCL Press. Jones, EL and Forrest, JD (1992) Underreporting of abortion in surveys of U.S. women: 1976 to 1988. Demography 29: 113-126. Jones, JH (1981) Bad Blood. New Yourk: Collier Macmillian. Katosh, JP and Traugott, MW (1981) The consequences of validated and self-reported voting measures. Public Opinion Quarterly 45: 519-535. SOCIAL DESIRABILITY IN CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH 207 Keillor, B, Owens, D and Pettijohn, C (2001) A cross-cultural/crossnational study of influencing factors and socially desirable response biases. International Journal of Market Research 43: 63-84. Khavari, KA and Mabry, EA (1985) Personality and attitude correlates of psychosedative drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 16: 159-168. Klassen, D, Hornstra, RK, and Anderson, PB (1975) Influence of social desirability on symptom and mood reporting in a community survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 43:448-452. Kozma, A and Stones, MJ (1987) Social desirability in measures of subjective well-being: A systematic evaluation. Journal of Gerontology 42:56-59. McCrae, RR (1986) Well-being scales do not measure social desirability. Journal of Gerontology 41 :390-392. McCrae, RR and Costa, PT (1983) Social desirability scales: More substance than style. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51 :882-888. Middleton, KL and Jones, JL (2000) Socially desirable response sets: The impact of country culture. Psychology & Marketing 17: 149-163. Moorman, RH and Podsakoff, PM (1992) A meta-analytic review and empirical test of the potential confounding effects of social desirability response sets in organizational behaviour research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 65: 131-149. Okazaki, S (2000) l\~ian American and white American differences on affective distress symptoms: Do symptom reports differ across reporting methods. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 31 :603-625. Page, WF, Davies, JE, Ladner, RA and Alfassa, J (1977) Urinalysis screened vs verbally reported drug use: The identification of discrepant groups. International Journal of the Addictions 12: 439-450. Park:, KB, Upshaw, HS and Koh, SD (1988) East Asians' responses to 208 Part III Western health items. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 19:51-64. Phillips, DL and Clancy, KJ (1972) Some effects of "social desirability" in survey studies. AJS 77:921-940. Reese, SD, Danielson, W A, Shoemaker, P, Chang, T and Hsu, H.-L. (1986). Ethnicity-of-interviewer effects among Mexican-Americans and Anglos. Public Opinion Quarterly 50: 563-572. Ross, CE and Mirowsky, J (1984) Socially-desirable response and acquiescence in a cross-cultural survey of mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 25: 189-197. Sampson, RJ and Lauritsen, JL (1997) Racial and ethnic disparities in crime and criminal justice in the United States. In M Tonry (Ed.) Ethnicity, Crime, and Immigration: Comparative and Cross-National Perspectives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Smith, PB and Bond, MH (1998) Social Psychology Across Cultures, Second Edition. Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom: Harvester Wheatsheaf. Stevenson, HC (1994) The psychology of sexual racism and AIDS: An ongoing saga of distrust and the "sexual other." Journal of Black Studies 25: 62-80. Strosahl, KD, Chiles, JA and Linehan, MM (1984) Will the real social desirability please stand up? Hopelessness, depression, social desirability, and the prediction of suicidal behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 52:449-457. Sudman, S, Bradburn, NM and Schwarz, N (1996) Thinking About Answers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Triandis, HC (1995) Individualism and Collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Triandis, HC, Marin, G, Lisansky, J and Betancourt, H (1984) Simpatia as a cultural script for Hispanics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 47:1363-1375. 209 SOCIAL DESIRABILITY IN CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH Tsushima, WT (1969) Responses of Irish and Italians of two social classes on the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Social Psychology 77:215-219. Turk Smith, S, Smith, KD and Seymour, K (1993) Social desirability of personality items as a predictor of endorsement: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Social Psychology l33: 43-52. Van de Vijver, FJR, and Leung, K (1997) Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Van Hemert, D. D. A., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., Poortinga, Y. H., & Georgas, J. (2001). Structure and Score Levels of the EysenckPersonality Questionnaire across individuals and countries. (in review) Warnecke, RB, Johnson, TP, Chavez, N, Sudman, S, O'Rourke, DP, Lacey, Land Horm, J (1997) Improving question wording in surveys of culturally diverse populations. Annals of Epidemiology 7:334-342. Watten, RG (1996) Coping Psychopathology 29:340-346. styles in abstainers from alcohol. Welte, JW and Russell, M (1993) Influence of socially desirable responding in a study of stress and substance abuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 17: 758-761. Williams, JE, Satterwhite, RC and Saiz, JL (1998) The importance of psychological traits. New York: Plenum Press.