Autopsy of an Orchestra: An analysis of factors

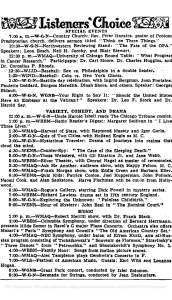

advertisement