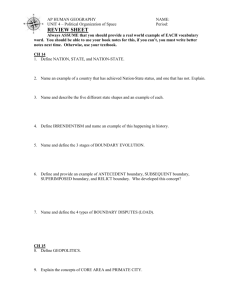

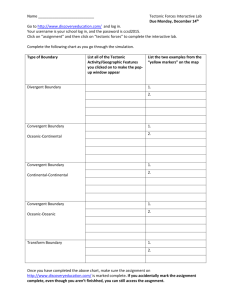

PROCEDURES FOR THE TRANSLATION OF BOUNDARY

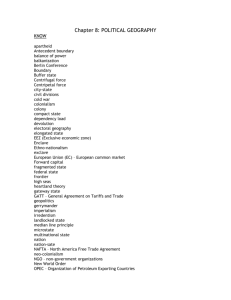

advertisement