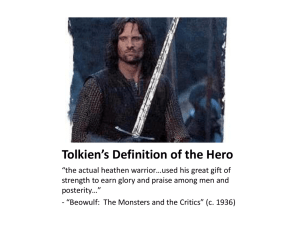

i RECREATING BEOWULF'S “PREGNANT MOMENT OF POISE

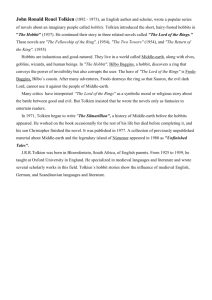

advertisement