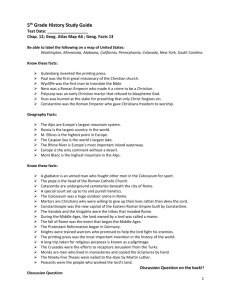

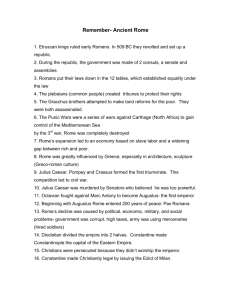

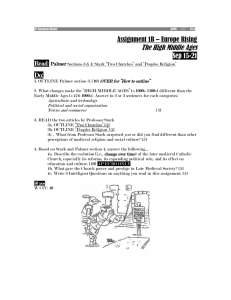

Conversion and Political Expedience: Imperial Themes in the Early

advertisement