The Goddess and the “Green Revolution”

advertisement

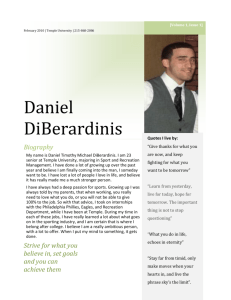

The Goddess and the “Green Revolution” How complex systems science helped restore Bali’s once-thriving rice terraces Inhabitants of the Indonesian island province of Bali are deeply connected to their centuries-old culture, especially when it comes to the cultivation of their land’s most vital crop: rice. The grain is so intrinsic to the Balinese diet, its indigenous name, nasi, is also the word for At a Glance “meal.” Restoring Bali’s Rice Terraces Bali’s landscape is filled with lush curving wetrice terraces, like the contour lines of a topographic map. For 1,000 years, farmers irrigated the fields they tended on these steppes with rainwater that flowed through a honeycomb of manmade tunnels built over the centuries. Despite the vast space set aside to cultivate rice, and the success farmers had in growing it, Indonesia was growing so rapidly that by the 1950s it had to import rice from abroad. The expectation of continued population growth meant something had to be done. Situation: New products and modern methods of farming meant to increase Bali’s rice production instead began to devastate the island’s crops. Solution: Applied complex systems modeling for transdisciplinary insights from anthropology, natural science, and religious studies to prove the superiority of Bali’s centuries-old farming methods. SFI scientist: Steve Lansing, External Professor Professor, University of Arizona Anthropology and Ecology & Evolutionary Biology Fertilize and Revolutionize The Asian Development Bank, part of the World Bank, and the Indonesian government decided in the mid-1970s that it was time to boost the production of rice on the island, and that the “Green Revolution” was the way to go about it. This term represented the introduction of modern agricultural science as a way to increase the agricultural yields of developing countries. Specifically, it meant new highyield varieties of grain and the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The new rice – dubbed “miracle rice” – and the modern chemicals increased Bali’s rice production exceedingly well. For a very short time. The bumper crops began to wane after the first year-and-a-half or so. In the traditional system, farmers coordinated their irrigation schedules Bali_Case_Study_110411.doc Results: • Halted an environmental catastrophe in Bali. • Balinese farmers encouraged to return to the religion-driven planting and irrigation methods their ancestors had optimized; rice production has subsequently returned to pre-Green Revolution levels. • A greater understanding of the need to examine numerous natural and human dynamics before introducing new methods into a complex adaptive system. • The Balinese water temple system is under consideration for World Heritage Site status. Page 1 of 4 and their fallow periods in order to bring down pest populations. The Green Revolution approach, however, required each farmer to plant rice as often as possible. This change caused the supply of irrigation water to become less predictable, and it made it easier for rice pests to migrate from field to field. As the farmers said, “Miracle rice has produced miracle pests.” Goddess of the Waters It was pure coincidence that Steve Lansing, a Santa Fe Institute external professor, was spending time in Bali studying its temples just as the Green Revolution was taking place. What was not coincidence, he believed, was that the decline of Bali’s rice harvests was occurring at the same time the farmers were ordered to abandon their traditional system of irrigation scheduling, which had long been coordinated through the water temple networks. The water temple rituals involved subaks, village-level groups of farmers whose crops rely on the same water sources. Subak members would gather each month at their local water temple where they coordinated cropping patterns and irrigation schedules. Once a year, temple representatives would gather at the supreme water temple, located at the island’s central lake and inhabited by, they believed, the goddess of the waters. Priests would collect holy water from the lake and portion it out to the representatives to bring back to their temples for local distribution. Ultimately, each farmer would receive a few drops to sprinkle over his fields as a symbol of the blessing of the Lake Goddess. Given the new variety of grain and the chemical marvels provided to help it grow, obtaining blessings from goddesses should have become unnecessary. However, as Steve saw the Bali_Case_Study_110411.doc Page 2 of 4 agricultural system begin to collapse, he suspected that the water temple rituals served a greater purpose: they enabled the subaks to strike an optimal balance between water sharing and controlling rice pests with synchronized fallow periods. Before the Green Revolution, this system worked so well it was effectively invisible, even to the farmers. The Green Revolution inadvertently revealed the functional role of the temple networks by disrupting the irrigation schedules. Steve explained the problem to the Asian Development Bank in an unsolicited report. In it, he recommended that the Bank allow the farmers to restore the temples to their traditional role in water management. The planners were unconvinced, arguing that the temples were suitable for native Balinese rice, but not for the faster-growing Green Revolution crops. A Model of Supreme Cooperation Steve’s response maintained that the temple networks did not impose a ritual clockwork on the irrigation schedules; instead they gave the farmers a flexible tool to adjust to changing environmental conditions. But the Bank remained unconvinced. So he and ecologist James Kremer devised a computer model to explore the effects of temple coordination on irrigation flows, pest outbreaks, and rice harvests for 172 subaks operating along two rivers. In the simulations, each subak would begin with a random cropping pattern and irrigation schedule. After every harvest, the subaks compared their yields to those of neighboring subaks. A subak would then adjust its cropping patterns and irrigation schedules to match those of its neighbor, only if the neighbor’s rice yields are higher. Shrine for Lake Goddess at an irrigation canal. Bali_Case_Study_110411.doc Page 3 of 4 No matter what “external” conditions the researchers changed in their model – rainfall, water flow, rice growth, pest biology – over several “modeling years” the virtual subaks adjusted their cropping patterns and irrigation schedules such that, without trying, synchronized patterns emerged and rice yields for the overall model were optimal. Moreover, the simulations always formed a near match of the subaks’ actual practices. “As we repeated these simulations,” says Steve, “we found that it is almost impossible not to grow a water temple system.” In other words, simulation models showed that temple networks self-organize, incrementally creating a globally optimal system of water use. This was a real-world example of a complex adaptive system with emergent properties, whose very existence had gone unnoticed until the simulation model revealed how it worked. Ending Agricultural Chaos Based on the modeling results, the Bank conceded. Bali’s water temple networks became a celebrated example of the emergent properties of a complex adaptive system – a new perspective that quickly spread in the fields of development and environmental science. In Bali, after the return to temple management, water was used more effectively, pest populations declined, and crop yields began to return to pre-Green Revolution rates. The water temple network is now being considered by UNESCO for recognition on its World Heritage list. Steve says, “Without the complexity perspective, this amazing system would very likely have gone unrecognized. It certainly would have been threatened by ongoing development projects that failed to recognize how it worked.” Fortunately, Bali’s wet-rice terraces, which the Balinese liken to faceted jewels, are thriving once again. SFI simulation models showed that temple networks self-organize, creating a globally optimal scale of water use. Bali_Case_Study_110411.doc Page 4 of 4