Research_Paper - Anastasia Marie

advertisement

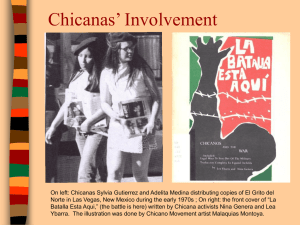

Rigoli 1 Alyssa Rigoli Dr. Dahlberg ENG 4312 April 25, 2015 Being Your Own Woman “I wasn’t going to be my mother or my grandma. All that self-sacrifice, all that silent suffering. Hell no. Not here. Not me” (Cisneros 127). Since the birth of the Chicano culture, women have been subject to the will of men. From their grueling beginning to the establishment of the culture based on myth and tradition, men have sought to keep their women in line and themselves in power. Women’s lives are planned out from birth; they are often arranged to be married to another boy before they even reach puberty. Chicano women are expected to be good wives and mothers, taking care of their families selflessly and without complaint, as did the Virgin of Guadalupe. They are seen as tools before women and women before people. Sandra Cisneros, author of “Woman Hollering Creek and other stories,” illustrates the immense obstacles that Chicano women must overcome in almost all of her stories. “The stories emphasize the tenacity of these icons’ [sexuality and motherhood] hold on Chicanas’ and Mexican Women’s self-images” (Wyatt 243). In one, “Little Miracles, Kept Promises,” a young woman named Rosario, nicknamed Chayo, finds strength within herself to be more than just a Chicana housewife. The hair that has never been cut is shorn from her head. Chayo, in her decision to cut off the braid that symbolizes the Chicana oppression, chooses to break from the traditional gender roles that have bound Chicano women for centuries, thereby exemplifying the struggle they face and the strength they have in overcoming those roles. To start, it is important to note the significance of a Chicano woman’s hair in order to Rigoli 2 understand the power Chayo displayed by cutting her braid. In “Women and Their Hair,” a study by Rose Weitz, it says, “For millennia, women’s subordinate position has been justified by an ideology that labeled their bodies and brains as inferior and has been reinforced by a unique set of disciplinary practices aimed at creating a submissive and ‘feminine’ body” (668). Practices like wearing dresses, not showing ankles, using make up to soften the face, and having long hair are examples of ways that emphasize an “inferior” form. Weitz emphasizes that “women’s rebellious hairstyles can allow them to distance themselves from the system that would subordinate them, to express their dissatisfaction, to identify like-minded others, and to challenge others to think about their own actions and beliefs” (670). In cutting her braid, Chayo makes the claim that she will not adhere to the so-called “values” of Chicano culture that prevent her from having her own identity. Another reason for cutting her hair may be the fact that “Latino and African American men…seem more often than white men to link long hair with attractiveness for women of all ages”; therefore, “to be most feminine and hence more attractive, women’s hair should be long, [and] curly or wavy…” (Weitz 672). One woman in Weitz study says, “If you wanted to have power, you needed to be like a boy, because when you acted like a girl, you didn’t get [what you wanted]” (677). Chayo does not want to marry, nor does she want to have children. She wants “to love something instead of someone,” and if she had children, she would have to do the latter (Cisneros 127). Chayo does not want to be bound to children or a husband, she wants to be free to pursue what she is passionate about. The women in Weitz study all say that they cut their hair short because it makes them feel more powerful, that they escaped the stereotype of femininity (677-678). Chayo’s cutting of her braid symbolizes this need to be powerful in a world where women are not seen as such. Continuing on, according to Maria Beltrán-Vocal, a professor at DePaul University, “Ser Rigoli 3 mujer y ser chicana han representado una serie de obstáculos y tabúes que la mujer ha debido vencer para lograr superarse y encontrarse a sí misma como individuo de dos culturas (To be a woman and a Chicana have represented a series of obstacles and taboos that the woman must have conquered to manage to overcome and be herself as an individual of two cultures) (trans. Rigoli)” (Beltrán-Vocal 139). She backs up these claims by referencing Sandra Cisneros’ stories about women overcoming gender roles and restrictions: that the main obstacles to acquiring their own identities in the stories are violence, familial oppression, the chauvinism of the Chicano male, the myth of the traditional Chicano woman, the Anglo-Saxon system, and suffering and selflessness (Beltrán-Vocal 140). Cisneros’ story about Chayo’s realization of identity and subsequent breaking of tradition is a prime example of this theme. Beltrán-Vocal further emphasizes that women are seen as mothers and wives before they are seen as people (139). She also claims that society holds fast to traditional ways of thinking and tries to avoid any type of change to those traditions, especially if they involve female empowerment (Beltrán-Vocal 140). Chayo’s passion being turned into a way for her to help the family (i.e. painting houses) is an example of how the Chicano culture promotes an all-inclusive relationship among members of a family. This serves to strengthen Chayo’s resolve to not be like the other women in her family. Beltrán-Vocal’s observations and analyses depict the enormity of the obstacle Chicano women face when they try to break free of their oppression. The male dominance as well as the generational teachings that women are less than men deprive them of any kind of self-identity, instead adhering to the male-imposed identities of their ancestors: mothers, wives, and housekeepers. So, for Chayo to cut off the symbol of her oppression is a strength that a lot of Chicano women still lack. In continuation, cultural myth has deprived Chicano women of the opportunity for Rigoli 4 individualism and personal success. Gloria Anzaldúa, in "The Homeland, Aztlan," speaks of the Chicano God of War and how he led the people to a place where an eagle, the symbol of masculinity, was clutching a serpent, the symbol of femininity, in its talons: The eagle symbolizes the spirit (as the sun, the father); the serpent symbolizes the soul (as the earth, the mother). Together, they symbolize the struggle between the spiritual/celestial/male and the underworld/earth/feminine. The symbolic sacrifice of the serpent to “higher” masculine powers… (27) Because of this, the patriarchal family has dominated over any matriarchal order. Furthermore, it illustrates, just like Beltrán-Vocal’s analyses, the immense difficulty Chicana women have in breaking the gender roles placed on them by ancient tradition that dates back to Pre-Columbian America. As an example, Sandra Cisneros makes an allusion to the myths in “Kept Promises, Little Miracles.” Chayo, in her letter to the Virgin of Guadalupe, says, “I’ve cut off my hair…Something shed like a snake-skin” (Cisneros 125). Making the simile to a snake-skin, Cisneros cunningly combines the symbol for Chayo’s gender restrictions with the image given by the God of War. In the act of cutting off her braid, Chayo sheds the skin of her gender restrictions. In fact, she does not even keep the plaited hair for posterity but offers it as a tribute to the Virgin not only as thanks for showing her the way to freedom but also apologies for denying her for so long. Chayo’s next statements delve further into the idea of the mythical traditions: “I’m a snake swallowing its tail. I’m my history and my future” (Cisneros 126). In this case, Cisneros is making an allusion to the Ouroboros, the depiction of a snake eating its own tail. It symbolizes repeating cycles (van der Sluijs and Peratt 17). Jean Wyatt, in her essay “On Not Being La Malinche,” also recognizes this: “The story…foregrounds the way that family and Rigoli 5 culture reflect and repeat a single gender definition, making a daughter’s identification with the social ideal of womanhood seem inescapable” (264). So, for Chayo to use the image of the Ouroboros, it means that she feels she is trapped in the endless cycle of oppressed women, and cutting off her braid is the final, desperate act of separation from that cycle. In Chicano culture, there are certain behavioral and social expectations for women. Alma Garcia, in her article “The Development of Chicana Feminist Discourse, 1970-1980,” discusses the misunderstanding that feminism undermines tradition. According to the Chicano community, the “ideal Chicana” was one “that glorified Chicanas as strong, long-suffering women who endured and kept Chicano culture and the family intact” (Garcia 222). Chicanas, by tradition, should emulate the example of the Virgin Mary, mother and wife, upholding cultural and familial values. Only through the accomplishment of being a supportive wife and mother would the Chicana be “fulfilled” as a woman (Garcia 222). By extension, the people in Chayo’s family cannot understand her unwillingness to be such a woman: “All the relatives are here. You come out of there and be sociable” (Cisneros 126). Chayo is expected to “come out and greet the relatives and smile and be nice and quedar bien” (Cisneros 126). She must be the proper Chicana and be supportive of her family no matter what; she is not allowed to think for herself or love anything except her family. Chayo must marry a man to be considered a benefit to the family: “Chayito, when you getting married? Look at your cousin Leticia. She’s younger than you” (Cisneros 126). Everything she does must be done toward having a husband and children. Even her passion is ridiculed: “Look at our Chayito. She likes making her little pictures. She’s gonna be a painter. A painter! Tell her I got five rooms that need painting” (Cisneros 126). She must put her family values before her own. Anything she does must benefit the family as a whole. If Chayo wants to be a painter, her family will find a Rigoli 6 way to make her use it for the benefit of all, not just for her own wishes and identity. Moreover, Chayo’s mother’s influence makes it even more difficult for her to throw aside her family’s beliefs. Steven Hitlin’s study, “Parental Influences on Children's Values and Aspirations: Bridging Two Theories of Social Class and Socialization,” covers the particular parental influences that affect the occupational, political, and social choices that children make. He argues that family values are often shared among parents and children. Hitlin goes on to say that female career choices are often mediated by mothers’ gender role ideology (28-29). This makes it a tremendous obstacle for Chayo, who grows up adhering to her mother’s direction on how she should act and believe, to come to the conclusion that she could never be who her family wants her to be. She can never be the braid-wearing, modest, subservient woman she is expected to become. Her time in an American university encourages a belief in selfdetermination, though her family does not see it as a benefit to her life. In fact, the family scorns the teachings of the university to speak her mind against the traditional gender roles, when Chicano women should be silent and accepting: “Is that what they teach you at the university? Miss High-and-Mighty. Miss Thinks-She’s-Too-Good-For-Us. Acting like a bolilla, a white girl. Malinche” (Cisneros 128). The insults thrown at her from ignorant women are almost too much for her. She tries to explain, but in vain. She does not want to be like her long-suffering mother and grandmother, who put up with the demeaning nature of Chicano tradition without comment, the way the Virgin did (Cisneros 127). Furthermore, Jean Wyatt’s essay “On Not Being La Malinche” reinforces the standing of Chicano cultural beliefs. She goes into the specific causes of gender roles in Chicano culture and the subsequent labels associated with them: Mexican social myths of gender crystallize with special force in three icons: “Guadalupe, Rigoli 7 the virgin mother who has not abandoned us, la Chingada (Malinche), the raped mother we have abandoned, and la Llorona, the mother who seeks her lost children.” According to the evidence of Chicana feminist writers, these “three Our Mothers” haunt the sexual and maternal identities of contemporary Mexican and Chicana women. Cherríe Moraga, for instance, asserts that “there is hardly a Chicana growing up today who does not suffer under [La Malinche’s] name.” (Wyatt 244) In the same regard, Chayo suffers through the gender identity given to her by her ancestors, without any way to convince her family otherwise. In the eyes of Chicano culture, women can imitate only the examples set forth by the “three Our Mothers” (Wyatt 244). If a woman is not a loving mother and wife like Guadalupe or a grieving, suffering woman of loss like La Llorona, she is the conniving, back-stabbing La Malinche, cast out of the culture the same way she cast out her people by giving her allegiance and her bed to the white man. There is no other option. So, by deciding to cut off her braid and question the values of the Chicano culture, Chayo becomes a traitor in the eyes of her family: “Don’t think I didn’t get my share of it from everyone. Heretic. Atheist. Malinchista. Hocicona…Don’t think it didn’t hurt being called a traitor” (Cisneros 127-128). However, “Cisneros considers Mexican icons of femininity to be intimately bound up with individual Chicanas’ and Mexican women’s self-images and selfesteem; to live with them comfortably—and there is no way to run away from them—each woman has to ‘make her peace with them’…” (Wyatt 244). Chicano women must look at the icons that dominate their culture and rise above the oppression of the men in order for them to discover who they really are. In the same way, in order for Chayo to find herself, she must face those icons head on; most importantly, she must confront her hatred of Guadalupe and understand just what the icon means to her. Rigoli 8 In truth, living in two different cultures puts a strain on Chayo. She confronts the traditions of her culture and the reality of the United States: that women are not subject to the whim of men, that they can not only have dreams and aspirations, but can also act on them and be who they want to be, not who they are expected to be. According to Wyatt, “the protagonists [of Cisneros’ stories] inhabit a border zone between Anglo and Mexican cultures where the perpetual clash and collision of two sets of signifiers, two systems of social myth, can throw any one culture’s gender ideology into question” (243). Such is the case in the story of Chayo’s quest for self-identity. Chayo recognizes the conflict for what it is and questions her place between the two cultures: “I’m a bell without a clapper. A woman with one foot in this world and one foot in that. A woman straddling both” (Cisneros 125). She has goals for herself, encouraged by the value of the Anglo culture, the pursuit of happiness. However, the Chicano culture’s values— that family prosperity outweighs personal endeavors, especially female ones—criticize and condemn her to the point where she rejects everything to do with it. Chayo has had to “steel and hoard and hone” herself and “push the furniture against the door and not let [the Virgin] in” (Cisneros 126). The Virgin symbolizes everything she hates about her culture: I couldn’t see you without seeing my ma each time my father came home drunk and yelling, blaming everything that ever went wrong in his life on her… Couldn’t look at you without blaming you for all the pain my mother and her mother and all our mothers’ mothers have put up with in the name of God. (Cisneros 127) She hates that women have to put with the whims and abuses of men. She hates that women only do so because tradition and, even worse, religion says to. To her, the Virgin models “the passive endurance of misery and oppression that she sees reflected in her mother and grandmother” (Wyatt 265). So, for years of her life, Chayo denies the Virgin in her home. Eventually, however, Rigoli 9 she comes to understand that the Virgin is more than a symbol of passivity. Later in her life, Chayo is able to look at the Virgin in a different light, spurring her on and supporting her decision to have her own identity apart from the Chicano gender roles. Chayo “acknowledges the Virgin’s other face—the face of Tonantzín…the aspect that, because it represents all the Mexican people, Indian as well as Mexican, can rally everyone to fight against oppression” (Wyatt 265). This realization of all that the Virgin stands for brings her to the realization of everything she, herself, stands for. Wyatt says that “Rosario [Chayo] does not settle on one side of the cultural border, then, not even on the side of power, but returns to read Mary’s (and her own mother’s) capacity for endurance through the strength of Tonantzín” (265). This acceptance helps her “see her mother’s and grandmother’s strength as real and to embrace her own female potential. It is the Virgen de Guadalupe’s biculturalism that gives her figure the capacity to empower different modes of being a woman” (Wyatt 265). Chayo can finally see herself in the different aspects of the Virgin. She can now see that the Virgin is not passive but strong in her resilience. With this in mind, she can finally open herself to independence. To continue, rebellion comes in many forms, even the act of cutting hair. When people cannot physically free themselves from their culture, they do so symbolically, in whatever ways improve their self-esteem and individuality. In Annette Hemmings’ study, “Navigating Cultural Crosscurrents: (Post)anthropological Passages through High School,” she follows the rebellion of several high school students, including a girl with a Chicano heritage, Christina Sanchez (135). According to Hemmings, Christina and her friends have “really strict” families: The girls in her clique were expected to dress in modest clothes, remain sexually abstinent until marriage, and adhere to kinship prescriptions. Yet they would show up in school wearing tight-fitting jeans, flirt with boys (Christina said she had a ‘secret Rigoli 10 boyfriend’), and otherwise cross up family expectations. (139) The frustration these girls have while they try to live in two different cultures is reflected in their decision to rebel in whatever little way they can. They are confined by cultural—and, by extension, familial—expectations, unable to be who they want to be, so they break the gender rules and restrictions. In Chayo’s case, it is the cutting of her braid that symbolizes her rebellion and freedom from Chicano gender roles. The braid, which she “ruin[ed] in one second what [her] mother took years to create,” was all that she could give to the Virgin both to thank her and to break free (Cisneros 125). When she finally becomes her own person, not bound by the traditions of her culture, Chayo cuts off her braid and can love the Virgin and herself (Cisneros 128). Finally, in writing the story of Chayo and her desire to break from gender roles, Cisneros provides a fictitious example of the strength Chicano feminists in the world have when they rise above their oppression. Ironically, the Chicano feminist movement began in the midst of the 60’s Chicano Movement, when Chicanos were fighting for cultural equality in the United States (Garcia 218). According to Garcia, “Their feminist consciousness emerged from a struggle for equality with Chicano men and from a reassessment of the role of the family as a means of resistance to oppressive societal conditions…Specifically, women began to question their traditional female roles” (219). In the fight for the equality of the Chicanos, women realized that their equality did not matter as much as male equality. So, they sought to fix that: “To them, feminism represented a movement to end sexist oppression within a broader social protest movement” (Garcia 220). Garcia states that there has been a history of feminist movements, not just for Chicanas but for other women of color, that occurred in response to “the constraints of male domination” within the larger racial movements (218). She goes into the issues regarding “cultural nationalism” through the use of quotes from leading Chicana feminists like Nieto Rigoli 11 Gomez: Chicana feminism is the recognition that women are oppressed as a group and are exploited as part of the la Raza people. It is a direction to be responsible and to identify and act upon the issues and needs of Chicana women. Chicana feminists are involved in understanding the nature of women’s oppression. (Garcia 221) Only other women can inspire their oppressed sisters to rise above and conquer their fears and weaknesses. It takes the realization that the oppression exists, first; then, it takes the strength to break free of the oppression. When that is done, it takes the will to help others do the same. Garcia further claims that the rise of Chicana feminists and their criticism of the Chicano movement was seen as a threat to the “political unity” of the movement and to the culture itself (224). The Chicano “loyalists,” as Garcia calls them, are those who seek to preserve the Chicano culture: “And since when does a Chicana need identity? If you are a real Chicana then no one regardless of the degrees needs to tell you about it. The only ones who need identity are the vendidas, the falsas, and the opportunists” (Garcia 225-226). These opposing beliefs within the culture provide a confusing argument for the women who want to be free. On the one hand, the feminists claim that they are being oppressed; on the other, friends and family argue that the feminists are “undermining the values associated with Chicano culture” (Garcia 225). It is a difficult choice to make, which in turn makes Chayo’s decision all the more amazing. In the end, Chayo’s realization of the strength in the Chicano woman and in herself allows her to breaks her chains of oppression by cutting her braid, a symbol of attractiveness and femininity in the eyes of her culture. Sandra Cisneros uses Chayo’s story to illustrate the horrific and often traumatizing obstacles that Chicano women face when trying to free themselves of the traditional gender roles binding them in their places of passivity and subjugation. The social and Rigoli 12 behavioral expectations of Chicano women are designed to make them willing, yet oblivious, subjects of oppression. They are taught from birth that the way they live is the right way to live and that any other way is the way of La Malinche. A woman is either a wife, mother, and housekeeper or a traitorous whore who is trying to destroy the Chicano way of life. Still, the icon of the Virgin in Chicano culture holds more truths than are seen at first glance. She is all at once the symbol of femininity, motherly and wifely love, and inherent strength. The Chicano women have this inner strength; it is what gets them through the hard times in their lives. They pray to the Virgin for strength because it takes a lot of it to provide and care for their families without complaint, completely self-sacrificing. In a way, Chayo’s sudden strength and ability to cut off the symbol of the Chicano gender roles stem from the very same myths that once bound her. Rigoli 13 Works Cited Anzaldúa, Gloria. "The Homeland, Aztlan." Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 2nd Ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999. 23-35. Digital Text. Beltrán-Vocal, María A. "La problemática de la chicana en dos obras de Sandra Cisneros: "The House on Mango Street y." Letras Femeninas (1995): 139-151. JSTOR. Web. Cisneros, Sandra. "Little Miracles, Kept Promises." Cisneros, Sandra. Woman Hollering Creek and other stories. New York: Vintage Books, 1991. 116-129. Print. Garcia, Alma M. "The Development of Chicana Feminist Discourse, 1970-1980." Gender and Society (1989): 217-238. JSTOR. Web. Hemmings, Annette. "Navigating Cultural Crosscurrents: (Post)anthropological Passages through High School." Anthropology and Education Quarterly (2006): 128-143. JSTOR. Web. Hitlin, Steven. "Parental Influences on Children's Values and Aspirations: Bridging Two Theories of Social Class and Socialization." Sociological Perspectives 2006: 25-46. JSTOR. Web. van der Sluijs, Marinus Anthony and Anthony L. Peratt. "The Ourobóros as an Auroral Phenomenon." Journal of Folklore Research (2009): 3-41. JSTOR. Web. Weitz, Rose. "Women and Their Hair: Seeking Power through Resistance and Accomodation." Gender & Society (2001): 667-686. Google Scholar. Web. Wyatt, Jean. "On Not Being La Malinche: Border Negotiations of Gender in Sandra Cisneros's "Never Marry a Mexican" and "Woman Hollering Creek"." Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature (1995): 243-271. JSTOR. Web. Rigoli 14 Other Works Consulted Ybarra, Lea. "When Wives Work: The Impact on the Chicano Family." Journal of Marriage and Family (1982): 169-178. JSTOR. Web.