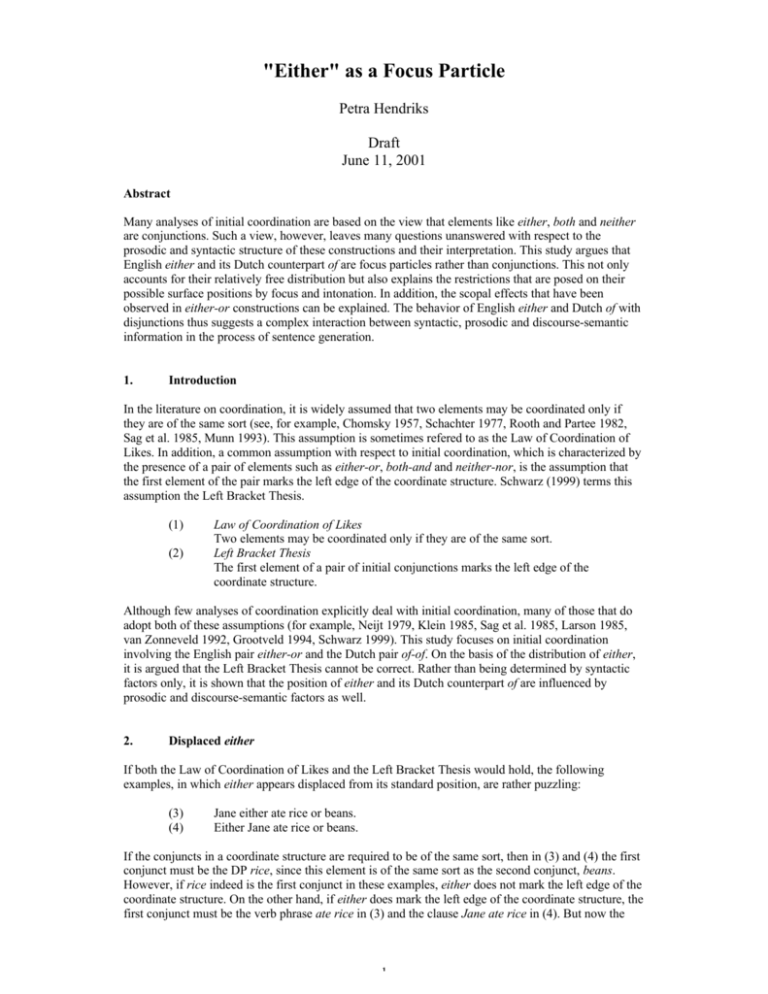

"Either" as a Focus Particle

advertisement