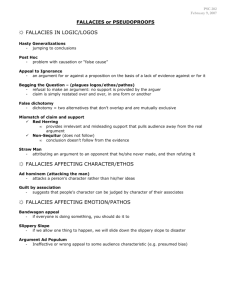

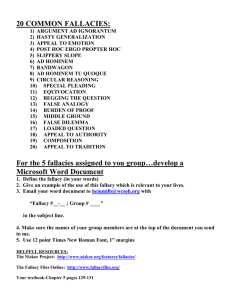

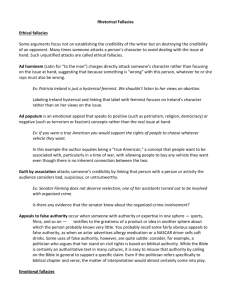

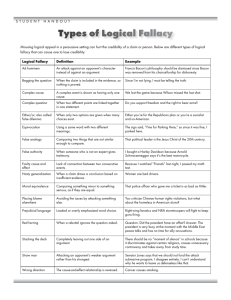

Informal Fallacies: Logic Textbook Excerpt

advertisement