Rhetorical Fallacies Handout

advertisement

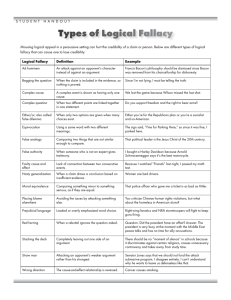

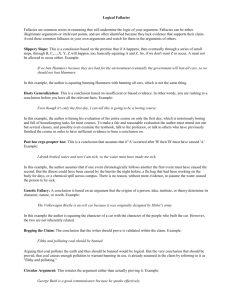

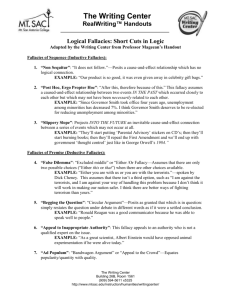

Rhetorical Fallacies Ethical fallacies Some arguments focus not on establishing the credibility of the writer but on destroying the credibility of an opponent. Many times someone attacks a person’s character to avoid dealing with the issue at hand. Such unjustified attacks are called ethical fallacies. Ad hominem (Latin for “to the man”) charges directly attack someone’s character rather than focusing on the issue at hand, suggesting that because something is “wrong” with this person, whatever he or she says must also be wrong. Ex: Patricia Ireland is just a hysterical feminist. We shouldn’t listen to her views on abortion. Labeling Ireland hysterical and linking that label with feminist focuses on Ireland’s character rather than on her views on the issue. Ad populum is an emotional appeal that speaks to positive (such as patriotism, religion, democracy) or negative (such as terrorism or fascism) concepts rather than the real issue at hand. Ex: If you were a true American you would support the rights of people to choose whatever vehicle they want. In this example the author equates being a "true American," a concept that people want to be associated with, particularly in a time of war, with allowing people to buy any vehicle they want even though there is no inherent connection between the two. Guilt by association attacks someone’s credibility by linking that person with a person or activity the audience considers bad, suspicious, or untrustworthy. Ex: Senator Fleming does not deserve reelection; one of her assistants turned out to be involved with organized crime. Is there any evidence that the senator knew about the organized-crime involvement? Appeals to false authority occur when someone with authority or expertise in one sphere — sports, films, and so on — testifies to the greatness of a product or idea in another sphere about which the person probably knows very little. You probably recall some fairly obvious appeals to false authority, as when an actor advertises allergy medication or a NASCAR driver sells soft drinks. Some uses of false authority, however, are quite subtle: consider, for example, a politician who argues that her stand on civil rights is based on biblical authority. While the Bible is certainly an authoritative text in many cultures, it is easy to misuse that authority by calling on the Bible in general to support a specific claim. Even if the politician refers specifically to biblical chapter and verse, the matter of interpretation would almost certainly come into play. Emotional fallacies Unfair or overblown emotional appeals, however, attempt to overcome readers’ good judgment. Bandwagon appeal suggests that a great movement is under way and the reader will be a fool or a traitor not to join it. Ex: Voters are flocking to candidate X by the millions, so you’d better cast your vote right away. Why should you jump on this bandwagon? Where is the evidence to support the claim that a vote for X is a vote cast “right”? Flattery tries to persuade readers to do something by suggesting that they are thoughtful, intelligent, or perceptive enough to agree with the writer. Ex: We know you have the taste to recognize the superlative artistry of Bling diamond jewelry. Would buying the jewelry prove that you recognize superlative artistry? In-crowd appeal, a special kind of flattery, invites readers to identify with an admired and select group. Ex: Want to know a secret that more and more of Middletown’s successful young professionals are finding out about? It’s Mountainbrook Manor, the condominiums that combine the best of the old with the best of the new. Who are these “successful young professionals,” and will you become one just by moving to Mountainbrook Manor? Veiled threats try to frighten readers into agreement by hinting that they will suffer adverse consequences if they don’t agree. Ex: If Public Service Electric Company does not get an immediate 15% rate increase, its services to you, its customers, may be seriously affected. How serious is this possible effect? Is it legal or likely? False analogies make comparisons between two situations that are not alike in most or important respects. Ex: The volleyball team’s sudden descent in the rankings resembled the sinking of the Titanic. What, other than “descent” and “sinking,” do the two have in common? Logical fallacies Although logical fallacies are usually defined as errors in formal reasoning, they can often work very effectively to convince audiences. Begging the question is a kind of circular argument that treats a debatable statement as if it had been proved true. Ex: Television news covered that story well; I learned all I know about it by watching TV. That “I learned all I know” about a story from television does not prove that television news covered the story well; the “proof” is just an assumption that the news covered the story well. The post hoc fallacy, from the Latin post hoc, ergo propter hoc, which means “after this, therefore caused by this,” assumes that just because B happened after A, it must have been caused by A. Ex: We should not rebuild the town docks because every time we do, a big hurricane comes along and damages them. Does the reconstruction cause hurricanes? A non sequitur (Latin for “it does not follow”) attempts to tie together two or more logically unrelated ideas as if they were related. Ex: If we can send a spacecraft to Mars, then we can discover a cure for cancer. These are both scientific goals, but do they have anything else in common? What does achieving one have to do with achieving the other? The either-or fallacy asserts that a complex situation can have only two possible outcomes, one of which is necessary or preferable. Ex: If we do not build the new aqueduct, business in the tri-cities area will be forced to shut down because of lack of water. What is the evidence for this claim? Do no other alternatives exist? A hasty generalization bases a conclusion on too little evidence or on bad or misunderstood evidence. Ex: I couldn’t understand the lecture today, so I’m sure this course will be impossible. How can the writer be so sure of this conclusion based on only one piece of evidence? Oversimplification of the relation between causes and effects is another fallacy based on careless reasoning. Ex: If we prohibit the sale of alcohol, we will get rid of drunkenness. This claim oversimplifies the relation between laws and human behavior. A straw-man argument misrepresents a real opposition argument as a kind of a dummy claim that can easily be refuted. Ex: My opponent believes that we should offer therapy to the terrorists. I disagree. This claim sets up the “straw man” of a plainly ridiculous opposition argument — who would not disagree? The opponent’s real position is almost certainly more nuanced. Slippery slope is a conclusion based on the premise that if A happens, then eventually through a series of small steps, through B, C,..., X, Y, Z will happen, too, basically equating A and Z. So, if we don't want Z to occur, A must not be allowed to occur either. Ex: If we ban Hummers because they are bad for the environment eventually the government will ban all cars, so we should not ban Hummers. In this example the author is equating banning Hummers with banning all cars, which is not the same thing. Genetic Fallacy is a conclusion based on an argument that the origins of a person, idea, institute, or theory determine its character, nature, or worth. Ex: The Volkswagen Beetle is an evil car because it was originally designed by Hitler's army. In this example the author is equating the character of a car with the character of the people who built the car. However, the two are not inherently related. Red Herring is a diversionary tactic that avoids the key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them. Ex: The level of mercury in seafood may be unsafe, but what will fishers do to support their families? In this example the author switches the discussion away from the safety of the food and talks instead about an economic issue, the livelihood of those catching fish. While one issue may affect the other it does not mean we should ignore possible safety issues because of possible economic consequences to a few individuals. Moral Equivalence is a fallacy that compares minor misdeeds with major atrocities. Ex: That parking attendant who gave me a ticket is as bad as Hitler. In this example the author is comparing the relatively harmless actions of a person doing their job with the horrific actions of Hitler. This comparison is unfair and inaccurate. Taken from: The St. Martin’s e-handbook & The Purdue Owl