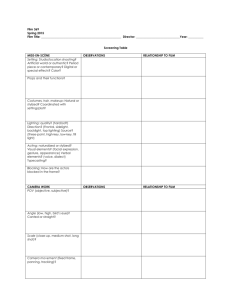

MISE-EN-SCENE

MISE-EN-SCENE

Mise-en-scène (French pronunciation: [miz ɑ s ɛ n] "placing on stage") is an expression used to describe the design aspects of a theatre or film production, which essentially means " visual theme " or " telling a story " —both in visually artful ways through storyboarding, cinematography and stage design, and in poetically artful ways through direction. Mise-en-scène has been called film criticism's "grand undefined term." [1]

When applied to the cinema, mise-en-scène refers to everything that appears before the camera and its arrangement—composition, sets, props, actors, costumes, and lighting.

[2]

Mise-en-scène also includes the positioning and movement of actors on the set, which is called blocking. These are all the areas overseen by the director, and thus, in French film credits, the director's title is metteur en scène , "placer on scene."

Interpretation

This narrow definition of mise-en-scène is not shared by all critics. For some, it refers to all elements of visual style—that is, both elements on the set and aspects of the camera. For others, such as U.S. film critic Andrew Sarris, it takes on mystical meanings related to the emotional tone of a film.

Recently, the term has come to represent a style of conveying the information of a scene primarily through a single shot—often accompanied by camera movement. It is to be contrasted with montage-style filmmaking—multiple angles pieced together through editing. Overall, mise-en-scène is used when the director wishes to give an impression of the characters or situation without vocally articulating it through the framework of spoken dialogue, and typically does not represent a realistic setting. The common example is that of a cluttered, disorganized apartment being used to reflect the disorganization in a character's life in general, or a sparsely decorated apartment to convey a character with an "empty soul" (e.g., Robert De Niro's house on the beach in Heat ), in both cases specifically and intentionally ignoring any practicality in the setting.

In German filmmaking in the 1910s and 1920s one can observe tone, meaning, and narrative information conveyed through mise-en-scène . Perhaps the most famous example of this is The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) where a character's internal state of mind is represented through set design and blocking.

The similar-sounding, but unrelated term, " metteurs en scène " (figuratively, "stagers") was used by the auteur theory as a disparaging label for directors who did not put their personal vision into their films.

[ citation needed ]

Because of its relationship to shot blocking, mise-en-scène is also a term sometimes used among professional screenwriters to indicate descriptive (action) paragraphs between the dialog.

Only rarely is mise-en-scène critique used in other art forms, but it has been used effectively to analyse photography.

Key aspects of mise en scene

Set design

An important element of "putting in the scene" is set design—the setting of a scene and the objects (props) there in. Set design can be used to amplify character emotion or the dominant mood of a film, or to establish aspects of the character.

Lighting

The intensity, direction, and quality of lighting have a profound effect on the way an image is perceived. Light (and shade) can emphasise texture, shape, distance, mood, time of day or night, season, glamour; it affects the way colours are rendered, both in terms of hue and depth, and can focus attention on particular elements of the composition.

Space

The representation of space affects the reading of a film. Depth, proximity, size and proportions of the places and objects in a film can be manipulated through camera placement and lenses, lighting, set design, effectively determining mood or relationships between elements in the story world.

Costume

Acting

Costume simply refers to the clothes that characters wear. Using certain colors or designs, costumes in narrative cinema are used to signify characters or to make clear distinctions between characters.

There is enormous historical and cultural variation in performance styles in the cinema. Early melodramatic styles, clearly indebted to the 19th century theatre, gave way in Western cinema to a relatively naturalistic style.

180° RULE

In filmmaking , the 180° rule is a basic guideline that states that two characters (or other elements) in the same scene should always have the same left/right relationship to each other. If the camera passes over the imaginary axis connecting the two subjects, it is called crossing the line . The new shot, from the opposite side, is known as a reverse angle .

Examples

In the example of a dialogue between two actors, if Mason(orange shirt in the diagram) is on the left and PJ(blue shirt) is on the right, then Mason should be facing right at all times, even when PJ is off the edge of the frame, and PJ should always be facing left. Shifting to the other side of the characters on a cut, so that PJ is now on the left side and Mason is on the right, will disorient the viewer, and break the flow of the scene.

In the example of an action scene, such as a car chase, if a vehicle leaves the right side of the frame in one shot, it should enter from the left side of the frame in the next shot.

Leaving from the right and entering from the right will create a similar sense of disorientation as in the dialogue example.

An example of sustained use of the 180 degree rule occurs throughout much of The Big

Parade , a 1925 drama about World War I directed by King Vidor. In the sequences leading up to the battle scenes, the American forces (arriving from the west) are always shown marching from left to right across the screen, while the German troops (arriving from the east) are always shown marching from right to left. After the battle scenes, when the weary troops are staggering homeward, the Americans are always shown crossing the screen from right to left (moving west) and the Germans from left to right (moving east). The audience's viewpoint is therefore always from a consistent position, in this case southward of the action.

Problems caused and solutions

The 180 degree rule enables the audience to visually connect with unseen movement happening around and behind the immediate subject and is important in the narration of battle scenes. The visual disjointedness of the battle scene on Geonosis in the Star Wars film Attack of the Clones is an example.

Avoiding crossing the line is a problem that those learning filmcraft will need to struggle with. In the above example with the car chase, a possible solution is to begin the second cut with the car driving into frame from the "wrong" side. Although this may be wrong in the geographic sense on set, it looks more natural to the viewer. Another possibility is to insert a "buffer shot" of the subject head-on (or from behind) to help the viewer understand the camera movement.

Style

In professional productions, the applied 180° rule is an essential element for a style of film editing called continuity editing. The rule is not always obeyed. Sometimes a filmmaker will purposely break the line of action in order to create disorientation. Stanley Kubrick was known to do this, for example in the bathroom scene in The Shining. The Wachowski

Brothers and directors Tinto Brass, Yasujiro Ozu, Wong Kar-wai, and Jacques Tati sometimes ignored this rule also, as has Lars von Trier in Antichrist .

The British television presenters Ant & Dec extend this continuity to almost all their appearances, with Ant almost always on the left and Dec on the right, as does the

Japanese pop duo PUFFY, with Yumi Yoshimura on the left and Ami Onuki on the right.

Some filmmakers state that the fictional axis created by this rule can be used to plan the emotional strength of a scene. The closer a camera is placed to the axis, the more emotionally involved the audience will be.

In the Japanese animated picture Paprika , two of the main characters discuss crossing the line and demonstrate the disorienting effect of actually performing the action.

In Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers , Gollum has a conversation with himself or with his other personality. Because the filmmakers use the 180 degree rule, and have the "good" Gollum looking left as he speaks while the "evil" Gollum looking right, the audience perceives Gollum as two different characters talking to each other.

30

° RULE

The 30° rule is a basic film editing guideline that states the camera should move at least

30° between shots of the same subject occurring in succession. This change of perspective makes the shots different enough to avoid a jump cut. Too much movement around the subject may violate the 180° rule.

As Timothy Corrigan and Patricia White suggest in The Film Experience , "The rule aims to emphasize the motivation for the cut by giving a substantially different view of the action.

The transition between two shots less than 30 degrees apart might be perceived as unnecessary or discontinuous--in short, visible." (2004, 130)

The rule is actually a special case of a more general dictum that states that the cut will be jarring if the two shots being cut are so similar that there appears to be a lack of motivation for the cut. In his book In The Blink of an Eye , editor Walter Murch states: “We have difficulty accepting the kind of displacements that are neither subtle nor total: Cutting from a full-figure master shot, for instance, to a slightly tighter shot that frames the actors from the ankles up. The new shot in this case is different enough to signal that something has changed, but not different enough to make us re-evaluate its context.” (2006, 6)

Following this rule may soften the effect of changing shot distance, such as changing from a medium shot to a close-up.

This sequence, 15 minutes (5:43) into Rose Hobart (1936), suggests a violation of the '30° rule' [1]

The axial cut is a striking violation of this rule to obtain a certain effect.