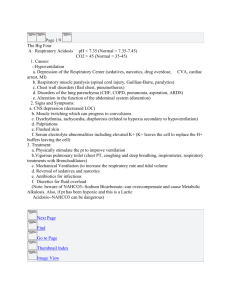

Care of the Child with Respiratory Disorders Care of the Child with

advertisement