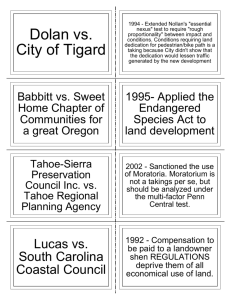

lingle's legacy: untangling substantive due process from takings

advertisement