View as a PDF - Saul Ewing LLP

advertisement

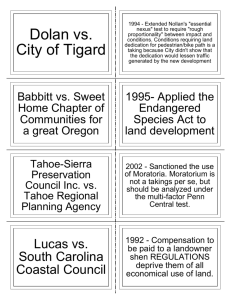

PHILADELPHIA, MONDAY, JANUARY 24, 2005 THE OLDEST LAW JOURNAL IN THE UNITED STATES R E A L E S TAT E Lingle and Other Cases Put Takings Tests in Spotlight Supreme Court Watch: BY MARTIN DOYLE AND DAVID FELDER Special to the Legal T he U.S. Supreme Court surprised observers recently by granting certiorari in yet another “takings” case for its current term. On Dec. 10, 2004, the Supreme Court granted a writ of certiorari to review San Remo Hotel, L.P. v. City and County of San Francisco, a case concerning a governmental ordinance restricting the use of a property as a hotel. Previously, the court had agreed to hear two other takings cases: Kelo vs. City of New London, a case concerning the authority of a governmental entity to take nonblighted private properties by eminent domain solely for economic development activities, and Lingle v. Chevron USA, Inc., which is the subject of this article. With San Remo on the docket, the court is now slated to hear more takings cases than any year since 1987, when it issued Keystone Bituminous Coal Association v. Debenedictis, First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. County of Los Angeles and Nollan v. California Coastal Commission. Lingle is surprising for another reason, because it represents the second 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision in recent months upholding a property owner’s takings claims. The 9th Circuit is normally considered highly unsympathetic to such claims. Lingle represents an appeal of the 9th Circuit case of Chevron USA Inc. v. Bronster, decided in April 2004. The Chevron case initially arose following the DOYLE FELDER MARTIN DOYLE and DAVID FELDER are members of Saul Ewing’s real estate department in the firm’s Philadelphia office. Both have worked on a number of major real estate transactions and have been involved in all aspects of real estate development, sales, finance and leasing. Doyle received a law degree, cum laude, from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Felder received his J.D. degree, cum laude, from Harvard Law School. 1997 enactment in Hawaii of Act 257, a law ostensibly designed to reduce the high cost of gasoline to retail consumers. Among other things, Act 257 imposed a limit on the maximum rent that an oil company could charge its dealers who lease their service stations from the company. Under the act, an oil company could not charge lessee-dealers rent in excess of the sum of 15 percent of the dealer’s profit on gasoline sales, 15 percent of the dealer’s gross sales revenue from other products, and a factor based upon increas- es in ground rents the oil company may be required to pay. At the time of the case, Chevron leased 64 service stations to independent dealers. Chevron had historically charged its dealers rent based upon estimated gasoline sales, but in 1997 instituted a nationwide rental program that restructured the rent calculation method. Under the new program, rents would have exceeded those allowed under Act 257 and were therefore capped. Consequently, the act had the impact of reducing these dealers’ rents, though not Chevron’s ground rents where applicable. Moreover, the act did not implicate either the ability of the dealer to sell its (rent-controlled) leasehold for a premium, or the ability of Chevron to exact a “transfer fee” in connection with the granting of its consent to any such transfer. Chevron filed a claim in the U.S. District Court for the District of Hawaii, asserting that Act 257 effected an unconstitutional regulatory taking without compensation. The Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution holds that private property may not “be taken for public use, without just compensation.” Over time, the Supreme Court has come to distinguish “physical” takings from “regulatory takings,” the latter being Chevron asserted that Act 257 effected an unconstitutional regulatory taking without compensation. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION OF THE LEGAL INTELLIGENCER cases where, though no property is actually taken, governmental regulation alone is alleged to go “so far” as to itself constitute a taking requiring compensation to effected parties. The district court cited several Supreme Court cases for the proposition that a land use regulation will be found to be a taking if it does not “substantially advance a legitimate state interest.” The court then held that the relevant state goals of protecting independent dealers and reducing gasoline prices were not substantially advanced, since dealers selling their businesses could capture (and thus impose upon their successors) the value of the rent cap premium, and oil companies could offset rent losses with increased wholesale gasoline prices. The court found the act’s impact to be similar to rent control provisions previously struck by the 9th Circuit in Richardson v. City and County of Honolulu. The court consequently granted Chevron summary judgment, holding that the act, failing to substantially advance legitimate state interests, was unconstitutional, violating the Fifth Amendment on its face. The state of Hawaii appealed the decision, and the 9th Circuit, in its first hearing of the case, vacated, finding that genuine issues of material fact existed concerning whether or not Act 257 failed to substantially advance its purpose of lowering retail gasoline prices. On remand, the district court again held that Act 257 was unconstitutional, issuing findings of fact and conclusions of law. The court made a fact finding that Act 257 would actually have the result of increasing retail gasoline prices, rather than causing them to decrease, concluding that oil companies will increase wholesale prices to offset lost rents, thereby increasing retail gas prices; that Act 257 will enable dealers to sell their stations as a premium, increasing required investment to enter the market; and that Act 257 will discourage oil companies from investing in new stations, thereby decreasing the number of dealerlessees (and reducing competition). Following the district court’s second decision, the state of Hawaii again appealed, this time arguing that the district court should have analyzed Chevron’s claim under the Due Process Clause, rather than the Takings Clause; that the court misapplied the requirement that the act substantially advance a legitimate state interest; and that it erred in finding that the act does not actually substantially advance a legitimate state interest. In its April 15, 2004, opinion, the 9th Circuit rejected these arguments. First, the court noted that the “law of the case doctrine” requires that the decision of an appellate court on an issue must be followed in all subsequent proceedings in the same case. Having determined in the first rehearing that the “substantially advances test” applied to this case, the court refused to reconsider whether the more deferential due process test should be applied. In so doing, the 9th Circuit opined that the “substantially advances” test for regulatory takings has survived the disparate Supreme Court opinions of Eastern Enterprises v. Apfel, reasoning that the questions posed in that case were narrow and different than those posed in Chevron and many other regulatory takings cases. The court further noted that Supreme Court opinions subsequent to Eastern Enterprises, specifically Tahoe Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v Tahoe Regional Planning Agency and City of Monterey v. Del Monte Dunes supported the vitality of the substantially advances test in takings cases. The court also rejected Hawaii’s argument that the applicable analysis was not “will the act accomplish its stated purpose?” but rather “could Hawaii rationally have believed that the act could have substantially advanced a legitimate government purpose?” The court, citing Nollan and other cases, noted that while due process claims can be analyzed under this “reasonable relationship” framework, the Supreme Court has specifically rejected this standard in regulatory takings cases. Takings cases which are properly analyzed under more deferential standards normally involve physical takings and are situations in which the government is presumed to be willing to pay compensation for the property it takes. Finally, the Chevron court rejected the state’s argument that the district court’s findings of fact were in error. Chevron affirms the perceived vitality of the “substantial advancement test,” which stands in contrast to the analysis for such cases set out in 1997 Supreme Court case of Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York. Penn Central laid down a much more qualitative balancing test, holding that a whether a regulation imposed on land constitutes a taking is dependent upon a variety of factors — generally, including the character of the governmental action, the actual economic impact on a property owner and the extent to which the regulation interferes with “investmentbacked expectations.” This less stringent test is viewed as helpful to the government in takings cases. In cases like Chevron, however, opponents of governmental regulations are provided with another (and in the right cases, more powerful) arrow in their quiver. A plaintiff may therefore choose its attack, and should consider its claim in light of each test to determine the most compelling case. In any event, it has been noted that, in light of cases such as Chevron, parties drafting regulations must now be more careful to ensure that those regulations, if open to a takings claim, not only assert a public interest, but can also satisfy the test of substantially advancing legitimate state interests. The three cases which the Supreme Court has agreed to hear in its current term — Lingle, San Remo and Kelo, may do a great deal to clarify the court’s developing views concerning the proper approach to disposition of regulatory takings cases. The stakes are large and these cases should be watched with interest, as their impact may be felt in many a wide range of areas. Lingle and Kelo are currently scheduled to be heard Feb. 22. San Remo will be heard in March. • REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION OF THE LEGAL INTELLIGENCER