Just a Flesh Wound

advertisement

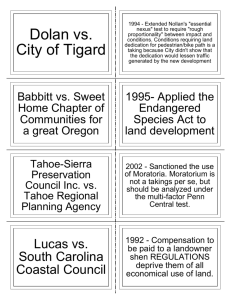

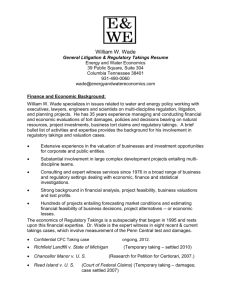

Pacific Legal Foundation Program for Judicial Awareness Just a Flesh Wound? The Impact of Lingle v. Chevron on Regulatory Takings Law by R. S. Radford Georgetown University Law Center Continuing Legal Education/Environmental Law & Policy Institute Litigating Regulatory Takings Claims, October 27-28, 2005 Cambridge, Massachusetts This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection (www.ssrn.com) Just a Flesh Wound? The Impact of Lingle v. Chevron on Regulatory Takings Law by R. S. Radford1 _________________________________________ ARTHUR: Now stand aside, worthy adversary. BLACK KNIGHT: ‘Tis but a scratch. ARTHUR: A scratch? Your arm’s off! BLACK KNIGHT: ARTHUR: No, it isn’t. Well, what’s that, then? BLACK KNIGHT: I’ve had worse.2 _________________________________________ 1 Director, Program for Judicial Awareness, Pacific Legal Foundation. Mr. Radford participated as amicus curiae in support of the property owners in Yee v. City of Escondido and Lingle v. Chevron, and is counsel of record in Cashman v. City of Cotati. 2 Monty Python and The Holy Grail (1975). Scene 4: The Black Knight. For some fifteen years after the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist took the reins of the Supreme Court, that tribunal regularly handed down decisions upholding and even enlarging upon constitutional protections of the rights of property owners. Yet throughout this period, disappointed advocates of regulation downplayed the long-term significance of these opinions, generally portraying them as having little precedential value beyond the facts then before the Court, and certainly marking out no fundamental shift in the constitutional balance of power between individual liberties and the regulatory state.3 With the Court’s latest trio of land-use decisions, coming at the conclusion of the Rehnquist Court, the shoe seems to have switched feet.4 This is especially true of Lingle v. Chevron, a decision that, on its face, repudiated a long-standing test of the constitutionality of land-use regulations under the Takings Clause: whether the measure in question substantially advances legitimate state interests. Although the decision was initially hailed as a death knell for property rights as meaningful claims against the state, more reasoned analysis quickly pointed out that Lingle is perhaps best understood as an exercise in sound and fury. As one commentator has already noted, On balance, this is not a win for government and not a loss for the property-rights advocates. Let us call this a draw. Government no longer has to defend against Agins-type takings claims, but there weren’t many of them regardless. You can be sure that 3 See, e.g., Note, Taking a Step Back: A Reconsideration of the Takings Test of Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, 102 Harv. L. Rev. 448 (1988); Richard J. Lazarus, Putting the Correct “Spin” on Lucas, 45 Stanf. L. Rev. 1411-32 (1993).; Richard J. Lazarus, Litigating Suitum v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, 12 J. Land Use & Envt’l L. 179-213 (1997). 4 See Lingle v. Chevron, U.S.A., Inc., 125 S. Ct. 2074, 2078 (2005); Kelo v. City of New London, 125 S. Ct. 2655 (2005); San Remo Hotel v. City and County of San Francisco, 125 S. Ct. 2491 (2005). 1 those who feel they have been shortchanged by government will find a new way to shove a burr under the saddle.5 Similarly, Prof. Barros has suggested that Lingle’s clarification of the dividing line between regulatory takings and violations of substantive due process may work to the long-term interests of propertyrights advocates more than the immediate effect of the decision may have injured them.”6 This sentiment is echoed by Michael M. Berger, who characterizes Lingle as “no blockbuster.”7 The majority of cases upholding Agins’ substantial advancement test as a viable takings claim arose in the Ninth Circuit, and – although this has somehow escaped general notice in the debates over the propriety of this standard – they all involved challenges to rent control. Not what most would regard as garden-variety apartment rent regulations, as they have existed for decades in California, and for generations in New York, but a special variety of regulations that pose special problems for a legal system that places great confidence in the presumed validity of the outcomes of a pluralistic democratic process. In this paper I briefly review the nature of these claims, and suggest that the same facts that previously led to takings liability under the substantial advancement test will simply be pled under a new cause of action in the future, arriving at the same result that would have pertained pre-Lingle. 5 Dwight H. Merriam, A Hat Trick in the Supreme Court for Government: Lingle, San Remo, and Kelo, 28 Zoning & Plan. L. Rep. 28:1 (Sept. 2005). 6 See D. Benjamin Barros, At last, Some Clarity: The Potential Long-Term Impact of Lingle v. Chevron and the Separation of Takings and Substantive Due Process (draft on file with author). 7 See Michael M. Berger, Recent Case Developments, ALI-ABA Course of Study: Inverse Condemnation and Related Government Liability 45, 47 (SL012, Sep. 29-Oct. 1, 2005). 2 I. The Origin and Significance of the Substantial Advancement Test In Yee v. City of Escondido,8 the Supreme Court in 1992 reviewed a challenge to the constitutionality of a mobile home park rent control ordinance. The plaintiffs alleged that Escondido’s rent ordinance was designed to allow tenants of regulated mobile home parks to capture the economic value of reduced rents as an incremental premium in the resale value of their mobile home coaches. By selling their rent-controlled coaches to new tenants, the park residents who had successfully lobbied for rent control could pocket the full cash value of the restrictions, leaving the incoming tenants (and society as a whole) in the same position as if rent control did not exist.9 The complaining parkowners alleged that this scheme violated the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment by authorizing a permanent physical invasion of their property, under the doctrine of Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp.10 An identical physical taking claim had been upheld by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals six years earlier, in Hall v. City of Santa Barbara.11 The Supreme Court, however, rejected this analysis. Justice O’Connor’s majority opinion noted that the essential feature of a Loretto-style taking is that the government “requires the landowner to submit to the physical occupation of his land” – a situation which the Court did not find to exist in Yee. The Court went on to point out, however, that the facts the parkowners advanced might fall 8 503 U.S. 519 (1992). 9 See id. at 523-27. 10 458 U.S. 419 (1982). 11 797 F.2d 1493, amended on denial of rehearing and rehearing en banc, 833 F.2 1270 (9th Cir. 1986). 3 “within the scope of our regulatory taking cases”12 by showing an insufficient “nexus between the effect of the ordinance and the objectives it is supposed to advance.”13 This was, of course, a reference to the “essential nexus” requirement of Nollan v. California Coastal Commission;14 a special case of the doctrine, first enunciated in Agins v. City of Tiburon,15 that a land-use regulation violates the Takings Clause if it fails to substantially advance legitimate state interests.16 Despite the urging of Judge Bork’s brief for the parkowners and an amicus brief filed in their support, the Yee Court declined to consider the merits of a takings claim based on the Escondido ordinance’s failure to substantially advance legitimate state interests, on the technical grounds that this question had not been presented in the petition for certiorari. This silence predictably gave rise to extensive litigation for more than a decade, in which a wide variety of rent control measures were challenged under the “failure to substantially advance” takings standard.17 The first of these cases to reach a resolution on the merits was Richardson v. City and County of Honolulu,18 which challenged a condominium rent control law as violating the substantial advancement standard. 12 Yee, 503 U.S. at 527. 13 Id. at 530. 14 483 U.S. 825 (1987). 15 447 U.S. 255 (1980). 16 Id. at 260. 17 See, e.g., Carson Harbor Village, Ltd. v. City of Carson, 37 F.3d 468 (9th Cir. 1994); Hacienda Valley Mobile Estates v. City of Morgan Hill, 353 F.3d 651 (9th Cir. 2003). 18 124 F.3d 1150. 4 As is the case with mobile home parks, there is normally divided ownership of condominiums on Oahu and the underlying land.19 The ordinance at issue in Richardson limited land-rent increases and specifically provided that the below-market rents were transferable, thereby facilitating capitalization of the financial benefits of rent control by condominium residents.20 As in the analogous case of mobile home parks, the Ninth Circuit recognized that “[i]ncumbent owner occupants who sell to those who intend to occupy the apartment will charge a premium for the benefit of living in a rent controlled condominium”21 Drawing on Yee, the court of appeals went on to note that this feature of the ordinance prevented it from substantially advancing legitimate governmental interests: The conveyance provision, as explained above [facilitating the capitalization and capture of the monetary benefits of rent control], vitiates the cause-and-effect relationship between the property use restricted (rent rates) and the social evil the Ordinance seeks to remedy (lack of affordable housing).22 19 See id. at 1163. 20 Id. at 1163-64. 21 Id. In striking down the Honolulu ordinance on summary judgment, the Federal District Court in Richardson made the resemblance to mobile home park rent control even more explicit: Like mobile home park tenants, owner-occupants of leasehold condominiums own their housing unit . . . but lease the underlying land. Moreover, the below-market rate lease rent which applies to the mobile home tenants and leasehold condominium owner-occupants is transferable to a subsequent purchaser of the mobile home pad or condominium. With respect to both mobile homes and condominiums, the availability of a below-market rate lease rent necessarily increases the value of the subject housing unit, thereby allowing a seller to command a premium upon the sale of the housing unit. Richardson v. City and County of Honolulu, 802 F. Supp. 326, 338 (D. Haw. 1992) (emphasis added). 22 Id. at 1165. 5 The same analysis was subsequently applied in Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Cayetano (Chevron I),23 a case in which Chevron alleged that restrictions on the rent it could charge lessee dealers of retail service stations violated the Takings Clause. The District Court agreed with Chevron that the regulations enabled incumbent dealers to capitalize the monetary value of reduced rents by selling their dealerships.24 The court explained: [t]he existence of the rent cap makes an independent dealer’s leasehold interest in a service station more valuable, and this added value becomes especially significant when an incumbent dealer undertakes to sell his interest. . . . Since the Act does not prohibit an incumbent dealer from selling his or her service station lease, the rent cap provision enables these dealers to sell their stations at a premium. 25 The Ninth Circuit found that summary judgment had been improperly granted because of the existence of conflicting expert testimony on whether the premium created by the regulations could be capitalized and captured by the dealers, or whether Chevron could offset this effect by adjusting the wholesale price of its gasoline.26 On remand, the District Court again found that Hawaii’s service station rent control scheme violated the Takings Clause.27 Twelve years to the day after Yee was decided, the Ninth Circuit affirmed in Chevron v. Lingle (Chevron II), 28 once again applying the substantial advancement standard to find the rent statute unconstitutional on its face.29 Covering 23 224 F.3d 1030 (9th Cir. 2000). 24 See Chevron v. Cayetano, 57 F. Supp. 2d 1003, 1010 (D. Haw. 1998). 25 Id. 26 See 224 F.3d at 1037-1040. 27 See Chevron v. Cayetano. 198 F. Supp.2d 1182 (D. Haw. 2002). 28 363 F.3d 846 (9th Cir. 2004). 29 See id. at 857-58. 6 much the same ground it had in Chevron I, the court of appeals again drew on Yee and Richardson as teaching “that application of the ‘substantially advances’ test is appropriate where a rent control ordinance creates the possibility that an incumbent lessee will be able to capture the value of the decreased rent in the form of a premium.”30 The panel considered and rejected a panoply of arguments the state leveled against the use of this analysis,31 and rebuffed the government’s plea for deferential review by noting that this option had been “specifically reject[ed]” by the Supreme Court in Nollan.32 While Chevron was being litigated, mobile home parkowners in the small California city of Cotati were pursuing a regulatory takings challenge to mobile home park rent control under the same substantial advancement theory. This case, Cashman v. City of Cotati,33 reached the Ninth Circuit in 2004. In a decision that closely tracked the legal analysis of Richardson and the two Chevron decisions, the Cashman panel reversed a trial court’s ruling that Cotati’s new rent ordinance passed constitutional muster, and held that an earlier order granting summary judgment to the park owners should be reinstated.34 The panel noted the case’s factual similarity to Richardson, which was also decided on summary judgment: Like in Richardson, there is no dispute that Ordinance No. 680 does not on its face prevent mobilehome tenants from capturing a premium. There is separate ownership of the mobilehome coaches and the underlying land, controlled rent, and the ability 30 Id. at 849. 31 Id. at 850-53. 32 Id. at 854 (citing Nollan, 483 U.S. at 825 n.3). 33 374 F.3d 887 (9th Cir. 2004). 34 See id. at 899. 7 of incumbent tenants to sell their mobilehomes subject to this controlled rent. This creates the possibility of a premium, which undermines the City's interest in creating or maintaining affordable housing.35 In contrast to the fact situation of Chevron, the Cashman court pointed to the absence of extraneous variables such as were present in the Hawaii case, that could potentially prevent Cotati’s tenants from capitalizing and capturing the rent control premium. 36 While a petition for rehearing was pending before the Ninth Circuit in Cashman, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in the Chevron case, now denominated Lingle v. Chevron.37 II. Lingle v. Chevron: A New Direction or a Judicial “Senior Moment?” Twelve years after Yee, the Supreme Court in Lingle revisited the application of the substantial advancement test to a rent control ordinance. Barely referring to her implicit invitation to bring such claims in Yee,38 Justice O’Connor now announced that the failure to substantially advance legitimate state interests, without more, does not state a claim for a violation of the Takings Clause.39 35 Id. 36 Id. at 898-99. 37 125 S.Ct. 314 (2004). 38 Yee was mentioned only as one of several decisions in which the Court had “merely assumed” the validity of the substantial advancement standard. See Lingle, 125 S.Ct. at 2086. 39 See id. at 2083 (repudiating the substantial advancement inquiry as a “freestanding,” or “stand-alone” takings test. 8 A unanimous Court in Lingle partially overruled Agins, to the extent of denying that the substantial advancement test, standing alone, was a takings standard at all.40 Repeating the common, but mistaken, understanding that the Takings Clause was not thought to apply to regulations at all prior to the Court’s 1922 decision in Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon,41 Justice O’Connor went on to twice describe Agins’ substantial advancement prong as a “means-ends” inquiry into the effectiveness of legislation.42 In so doing, she repeated the characterization of that standard advanced by the State of Hawaii, the Solicitor General, and a series of law review articles,43 without seeming to recall that this was not in fact how the Court understood and applied the substantial advancement test in the first place. The obvious alternative interpretation – that the Ninth Circuit had misapplied the substantial 40 Id. at 2082. 41 See id. at 2081. Professor Ely charitably describes this proposition as “historically dubious.” James W. Ely, Jr., “Poor Relation” Once More: The Supreme Court and the Vanishing Rights of Property Owners, in CATO SUPREME COURT REVIEW 2004-2005 50 (Mark K. Moller, ed., 2005). For pre-Pennsylvania Coal consideration of the doctrine of regulatory takings, see id. at 4243. 42 See Lingle, 125 S.Ct. at 2083, 2085. 43 See, e.g., Edward J. Sullivan, Emperors and Clothes: The Genealogy and Operation of the Agins Tests, 33 Urb. Law. 343 (2001); John D. Echeverria, Takings and Errors, 51 Ala. L. Rev. 1047 (2000); John D. Echeverria, Does a Regulation That Fails to Advance a Legitimate Governmental Interest Result in a Regulatory Taking?, 29 Envtl. L. 853 (1999): John D. Echeverria & Sharon Dennis, The Takings Issue and the Due Process Clause: A Way Out of a Doctrinal Confusion, 17 Vt. L. Rev. 695-721 (1993); Glen E. Summers, Comment, Private Property Without Lochner: Toward a Takings Jurisprudence Uncorrupted by Substantive Due Process, 142 U. Pa. L. Rev. 837-885 (1993). 9 advancement inquiry in Lingle, and that the standard retained its original vitality as a cause-effect takings inquiry44 – did not seem to occur to Justice O’Connor or any other member of the Court. This mental lapse seems especially odd since this very issue had been highlighted to the Court – and apparently played a major role in its deliberations – in Nollan. The amicus brief submitted by the Solicitor General in that case stressed that the constitutionality of the California Coastal Commission’s application of the Coastal Act to the Nollan’ proposed expansion of their beachfront home “turns on the relationship between the government’s justifications for the condition and the burdens that would be imposed on the public by the activity being regulated or restricted.”45 The general rule advocated by the Solicitor General was that a regulatory imposition must be “reasonably proportional both in character and degree to the burdens imposed by Appellants’ development.”46 Although the Nollans themselves did not raise the substantial advancement question per se, they argued throughout that the proper test was whether the expansion of their home created any special harms or burdens that could justify the Coastal Commission’s extortionate regulatory demands. For example, in responding to the Commission’s argument that its exaction was imposed pursuant to the important public objective of uninterrupted coastal access, the Nollans observed: 44 For fuller elaboration of this understanding of the substantial advancement standard, see R. S. Radford, Of Course a Land Use Regulation That Fails to Substantially Advance Legitimate State Interests Results in a Regulatory Taking, 15 Fordham Envt’l L. J. 353 (2004); Larry Salzman, Twenty Five Years Of The Substantial Advancement Doctrine Applied To Regulatory Takings: From Agins to Lingle v. Chevron, 35 Envt’l L. Rep. 10481 (2005). 45 Brief for the United Stattes as Amicus Curiae Supporting Reversal, Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, No. 86-133, at 21. 46 Id. 10 The relevant relationship in a meaningful “taking” analysis is not the relationship between the exaction and the public need, but rather the relationship between the exaction and the owners’ proposed use.47 In other words, the constitutional propriety of the regulatory imposition was expressly tied to the existence of a causal relationship between the proposed land use and the objective sought to be achieved by a regulatory constraint. The Coastal Commission, on the other hand, persistently argued that it should prevail under a means-ends analysis – a rationale that the Court seemingly recognized as inapposite when it applied the substantial advancement test in favor of the Nollans. Nor was the Nollan Court concerned that the property owners in that case were seeking invalidation as a remedy for a regulatory imposition that would violate the Takings Clause if not accompanied by compensation. Indeed, a memo prepared by the Legal Office of the Court on this issue dismissed as “disingenuous” the Coastal Commission’s argument that, by not seeking just compensation as a remedy, the Nollans had waived their takings claim. 48 Inexplicably, however, the Lingle Court vigorously asserted (without analysis) that seeking an invalidation remedy, instead of compensation, was a veritable hallmark of substantive due process. This, coupled with the Court’s loss of clarity in its previous understanding of substantial advancement as a causal inquiry, raises troubling issues concerning the expected longevity of any Supreme Court precedent, at least in the field of property rights. For as long as it lasts, however, Lingle apparently restricts the substantial advancement takings standard to its “essential nexus” and “rough proportionality” guises, to enjoy continued vitality in the special case of challenges to subdivision 47 Appellants’ Brief Opposing Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, No. 86-133, at 9. 48 See Supreme Court Conference Memo dated December 12, 1986, Case No. 86-133, “Motion of Appellee to Dismiss the Appeal,” signed [Richard] Schickele, at 6. 11 exactions.49 Otherwise, allegations of failure to substantially advance legitimate state interests must be couched in terms of a deprivation of substantive due process,50 or else folded into the amorphous balancing framework of Penn Central51 It seems plain, as Prof. Ely, has commented, that Lingle was the product of a Court that “seem[ed] to have lost its way and backtracked.”52 What is not so clear is, exactly where will this backtracking lead? III. Whither the Substantial Advancement Inquiry in Land-Use Cases? A. Substantive Due Process Justice Kennedy’s concurrence in Lingle stressed the availability of a due process remedy for “failure to substantially advance” claims.53 In appearing to anchor future use of this analysis in the Due Process Clause, Kennedy echoed his concurrence in Eastern Enterprises v. Apfel,54 in which he found the regulatory imposition of retroactive financial liability to violate substantive due process under a substantial-advancement inquiry.55 A due process cause of action is a more obvious intuitive match for the remedy that has normally been sought in substantial advancement takings claims, invalidation of the offending 49 See Lingle, 125 S.Ct. at 2087. 50 See id. at 2083-84. 51 See id. at 2087. 52 James W. Ely, Jr., “Poor Relation” Once More, supra note 41, at 39. 53 See Lingle, 125 S.Ct. at 2087 (Kennedy, J., concurring). 54 524 U.S. 498, 539 (1998) (Kennedy, J., concurring). 55 See id. at 539-50. 12 regulation. But the Lingle Court failed to consider an important anomaly in Ninth Circuit practice: since 1996, that circuit has barred substantive due process claims on facts that could set out a cause of action for a taking – including complaints based on failure to substantially advance legitimate state interests.56 In the Cashman case reviewed above,57 the Ninth Circuit granted the City of Cotati’s petition for rehearing, dismissing the case under Lingle.58 The parkowners, however, responded with their own petition for rehearing, arguing that the facts they had established at summary judgment should now be evaluated as setting forth a substantive due process violation – which courts in the Ninth Circuit were not allowed to entertain prior to Lingle!59 Moreover, a major concern for litigants bringing “substantial advancement due process” claims will be the appropriate standard of review. Justice Kennedy’s Lingle concurrence seems to assume that such claims would be subject to the deferential, “arbitrary and capricious” standard traditionally associated with substantive due process review. However, that would be directly contrary to the requirement of heightened scrutiny for substantial advancement claims set out in Nollan.60 Indeed, it would conflict with the higher standard of review Kennedy himself seemed to 56 See Armendariz v. Penman, 75 F.3d 1311, 1324 (1996). 57 See supra, text at notes 74-78. 58 Cashman v. City of Cotati, 415 F.3d 1027 (9th Cir. 2005). 59 See Cashman v. City of Cotati, No. 03-15066, Petition for Panel Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc, filed July 29, 2005. 60 483 U.S. at 825 n.3. 13 invoke for “substantial advancement due process” claims in Eastern Enterprises.61 How this conflict will be resolved is unforeseeable, especially given the Court’s recent propensity to dismiss its own precedent with a casual, “Oops!” In terms of the judicial protection of individual rights, forfeiting the first prong of Agins as a regulatory takings test could be considered an acceptable trade-off for the restoration of meaningful judicial review under the rubric of substantive due process.62 B. Penn Central’s “Character” Prong In recent years, the Supreme Court has increasingly channeled its taking jurisprudence into the analytical framework of Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York,63 which has been referred to as the “pole star” of the Court’s regulatory takings doctrine.64 Unfortunately, this focus on Penn Central has had something of the character of a default, resulting from the Court’s divesting itself, over the past few years, of the more specific takings standards it had set out in post-Penn Central decisions.65 While an analytical framework can be discerned in Penn Central (part of it being 61 See 524 U.S. at 545 (Kennedy, J., concurring) (arguing that a substantive due process claim is an appropriate vehicle to review “the legitimacy of Congress’ judgment”). 62 See, e.g., Norman Karlin, Substantive Due Process: A Doctrine for Regulatory Control, in RIGHTS AND REGULATION 43, 61 (Tibor R. Machan & M. Bruce Johnson, eds.,1983) (“Once it becomes clear that legislation and regulation that impose restraints on the market produce . . . harmful effects . . . , it becomes unclear why such legislation carries with it a presumption of validity”). 63 438 U.S. 104. 64 See Palazzolo v. Rhode Island, 533 U.S. 606, 633 (2001) (O’Connor, J., concurring); Tahoe-Sierra, 535 U.S. at 336. 65 Lingle overruled the “substantial advancement” standard the Court had set out in Agins and applied or upheld on three subsequent occasions; while Tahoe-Sierra both rejected the majority opinion in First English Evangelical Lutheran Church of Glendale v. County of Los Angeles, 482 U.S. 304 (1987), and effectively limited the “categorical” takings standard of Lucas to the facts of that case. 14 little more than a condensed version of a 1967 article in the Harvard Law Review),66 none of its key elements has been defined with any degree of precision.67 Determining how “failure to substantially advance” claims fit – if at all – into the Penn Central framework must therefore be worked out on a case-by-case basis, much as if the Supreme Court’s takings decisions over the past 27 years had never occurred. Following Michelman, the Penn Central Court set out a dual line of inquiry,68 noting that whether a land use regulation rises to a violation of the Takings Clause depends on the measure’s economic impact on the landowner and the “character of the government action.”69 The economic impact prong has been the subject of considerable analysis, both in case law and legal scholarship. 66 See Frank I. Michelman, Property, Utility, and Fairness: Comments on the Ethical Foundations of “Just Compensation,” 80 Harv. L. Rev. 1165 (1967). 67 See, e.g., Gideon Kanner, Making Laws and Sausages: A Quarter-Century Retrospective on Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York, 13 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 653 (2005); John D. Echeverria, The Once and Future Penn Central Test, 54 Land Use L. & Zoning Digest 6:19 (2002). 68 This two-pronged inquiry, in all essentials the equivalent of the Agins test, has almost uniformly been interpreted as a three-pronged standard. However, Penn Central’s reference to “investment backed expectations” was clearly included within the economic impact criterion. See, e.g., Steven J. Eagle, Planning Moratoria and Regulatory Takings: the Supreme Court's Fairness Mandate Benefits Landowners 31 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 429, 449 (2004) (“[I]t is not immediately obvious that investment-backed expectations are anything more than a subset of economic impact.”); John D. Echeverria, Is the Penn Central Three-Factor Test Ready for History’s Dustbin?, 52 Land Use & Zoning Dig. 3, 7 (2000) (noting that Penn Central’s supposed three-factor test “may only be a two-factor test”). In any case, the owner’s reasonable expectation of a property’s development potential is more appropriately considered as an element in determining the amount of compensation due for a taking, rather than in evaluating takings liability per se. See, e.g., R. S. Radford & J. David Breemer, Great Expectations: Will Palazzolo v. Rhode Island Clarify the Murky Doctrine of Investment-backed Expectations in Regulatory Takings Law? 9 N.Y.U. Envtl. L.J. 449, 526-30 (2001); Palm Beach Isles Associates v. United States, 231 F.3d 1354, 1363-64 (Fed. Cir. 2000). 69 Penn Central, 438 U.S. at 124. 15 Empirical evidence of the magnitude of the one-time wealth transfer facilitated by mobile home park rent control would obviously be relevant to this aspect of the Penn Central inquiry, since the amount of the premium capitalized by tenant-lobbyists into the resale price of their coaches mirrors the reduction in value of the parkowner’s land. But evidence that the dominant function of such regulations is merely to facilitate a one-time, private wealth transfer might be equally pertinent to Penn Central’s “character of the government action” prong. What considerations might reasonably be included in the “character” calculus remains as great a mystery today as the day Penn Central was drafted. One commentator has gone so far as to observe, “[t]he so-called ‘character’ factor is the most confused and confusing feature of regulatory takings doctrine.”70 Justice Brennan’s majority opinion in Penn Central offered scant insight into the meaning of this inquiry, saying only: A “taking” may more readily be found when the interference with property can be characterized as a physical invasion by government than when interference arises from some public program adjusting the benefits and burdens of economic life to promote the common good.71 Only four years later, the Court carved out permanent physical invasions as categorical takings not subject to Penn Central’s balancing test.72 Thus, the above passage can be read as contrasting temporary physical intrusions with measures that redistribute resources “to promote the 70 John D. Echeverria, The “Character” Factor in Regulatory Takings Analysis, ALI-ABA Continuing Legal Education: Wetlands Law and Regulation, SK081 ALI-ABA 143, 145 (June 9-10, 2005). 71 Penn Central, 438 U.S. at 124. 72 See Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419 (1982). 16 common good.”73 But are we to understand these two cases as some sort of binary opposition that together encompass all possible kinds of land-use regulations,74 or as two points on some sort of continuum? Or perhaps, just two random examples plucked willy-nilly from the unbounded universe of regulation-space? Given the hasty and imprecise drafting that characterize Penn Central,75 the latter possibility may be the most likely. Similarly, Penn Central’s “economic impact” prong was elevated to the status of a “categorical” test in Lucas.76 In such cases, the “character” inquiry is not only not determinative, it is irrelevant.77 73 It should be noted in passing that a straightforward inquiry into whether a land-use regulation in fact “promotes the public good” would today either be barred from the takings inquiry altogether under Lingle, or else would amount to an inquiry into whether the alleged taking was for a “public use,” under Kelo v. City of New London, 125 S.Ct. 2655. 74 See Steven J. Eagle, “Character” as “Worthiness”: A New Meaning for Penn Central’s Third Test?, 27 No. 6 Zoning & Planning L. Rep. 6:1, *2 (2004) (“This division implies that governmental actions respecting private property constitute either a physical usurpation or an adjustment in the benefits and burdens in the everyday life of citizens.”) (emphasis added). 75 See, e.g., Kanner, supra note 67, at 707 (“[I]t is certain that the U.S. Supreme Court's Penn Central opinion was drafted in haste. The case was argued on April 17, and the opinion filed on June 26, 1978. This timing suggests that it was a product of the notorious end-of-the-term crush of opinions being rushed to completion before the end of the Court’s term on June 30.”); John D. Echeverria, Is the Penn Central Three-Factor Test Ready for History’s Dustbin?, 52 Land Use & Zoning Dig. 3, 7 (2000) ([T]he Penn Central test ... is so vague and indeterminate that it invites unprincipled, subjective decision making by the courts.). 76 See Lucas, 505 U.S. at 1016-17. 77 See, e.g., Laura Lydigsen, Note, “Fairness and Justice” after Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency: Subsequent Regulatory Takings Decisions under the “Parcel as a Whole” Framework, 82 Wash. U. L.Q. 1513, 1522 (2004) (In Lucas, [i]t was unnecessary to consider the character of the government action or the reasonableness of the plaintiff’s interest because the lower court found that the plaintiff’s property lost all economic value under the 1988 Act. Thus, the Lucas categorical rule provided a property owner with compensation without (continued...) 17 Scholars who have addressed the nature of Penn Central’s “character” prong are broadly in agreement that the test must somehow relate to the considerations of fairness that have animated much of the Court’s recent takings jurisprudence. Professor Eagle has observed the importance of this factor in evaluating the “worthiness of the government’s regulatory purpose,” which he posits as the core function of the character inquiry. 78 Similarly, John Echeverria has noted the Court’s concern with singling out one or a few property owners to unfairly bear the brunt of a regulatory burden, without enjoying any offsetting benefits,79 and has suggested that [R]eciprocity of advantage might usefully be deployed to give some content to the ‘character’ factor. When a regulation necessarily creates a significant degree of reciprocity of advantage, the character factor arguably points toward rejection of the taking claim.”80 77 (...continued) requiring an evaluation of the Penn Central ad hoc factual inquiries so long as the property owner instead showed that he had been deprived of “all economically beneficial or productive use” of the property”) (footnotes omitted). When the economic impact prong dominates the analysis, investment-backed expectations likewise become irrelevant to the takings equation. See, e.g., R. S. Radford & J. David Breemer, Great Expectations: Will Palazzolo v. Rhode Island Clarify the Murky Doctrine of Investment-Backed Expectations in Regulatory Takings Law?, 9 N.Y.U. Envtl. L.J. 449, 472-78 (2001). 78 See Eagle, “Character” as “Worthiness”, supra note 74; see also Steven J. Eagle, “Character of the Governmental Action” in Takings Law: Past, Present, and Future, ALI-ABA Continuing Legal Education: Inverse Condemnation and Related Government Liability, SJ052 ALIABA 459, ___ (April 22-24, 2004); 79 See Echeverria, The “Character” Factor in Regulatory Takings Analysis, supra note 70, at 159-60. 80 John D. Echeverria, The Once and Future Penn Central Test, 54 Land Use L. & Zoning Dig. 6:19, 21 (2002). 18 This interpretation is consistent with what appears (at least in retrospect) to have been the operational normative principle underlying the Penn Central decision.81 Under this view, the nature of mobile home park rent control and analogous schemes that function primarily to capture and transfer financial windfalls between private individuals may be dispositive of Penn Central’s concern with the character of the government action. The same economic analysis and empirical research that previously informed “failure to substantially advance” takings claims can be relatively smoothly transitioned into the Penn Central framework. On one point, counsel for property owners and regulatory entities can probably agree: let us hope the Court doesn’t wait another twelve years to decide whether this is really what it had in mind. # # 81 # See Penn Central, 438 U.S. at 131-35 (evaluating at length Penn Central’s claim that it had been singled out to bear the cost of New York’s landmark preservation program, and concluding that the regulations spread offsetting benefits across the city). 19