The Lamb: the paganism in William Blake's poem

advertisement

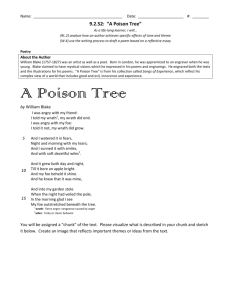

The Lamb: the paganism in William Blake’s poem By Marina Silveira Lopes and Emmanuel Gonçalves Guimarães Lisboa** Abstract: this work examines the poem The Lamb by the British poet William Blake. It is divided into three parts: firstly it considers the relevance of literary critical analysis, then, it makes some considerations about the poem itself and, finally, it tries an interpretation of it. Commentary Commentary is understood as the background of the poem. According to Antonio Cândido1 it is the historical-literary context in which the author is inserted. We deal here with a poem translated from English into Portuguese. It is a hard and thankless task because it is well known that there are insurmountable syntactic, semantic and orthographic differences between the British Isles language and the Lusitanian Portuguese. A very trivial example is the possibility of changing the positioning of the phrase elements in Portuguese whereas in English there is no such flexibility. On the other hand, in the original, we see an idiom that allows multiple meanings for the same word and in the translated text we have a language that has a great deal of semantemes for the same meaning with different signification. All this difference becomes much more complex when we are dealing with a poem because it is almost impossible to dissociate this type of text from sound, rhythm, cadence etc of the language in which it was written2. Another aspect that contributes to make difficult such analysis is the historical distance between the historical context of the poem and now when we are analyzing it. It is a text written in the XVIII century in England and we are analyzing it in Brazil in the XXI century. Taken into account such difficulties already mentioned by Antonio Cândido: “The commentary is a kind of translation done before the interpretation, […] The commentary is as much necessary as the text is far from us in time and semantic structure”3. We tried to find a translation that could meet our analysis criteria. We did not find it, so we made our own. To all elements of analysis pointed out by the USP’s illustrious professor of Brazilian Literature we added another to examine the poem. We emphasized religion as an indispensable factor for the building of the text. Religion is a factor that acts upon the artist’s work whether he wishes or not. For Antonio Carlos de Melo Magalhães “literature is the interpreter and the archive of the religious memory and experience”4. The manuals of literary studies place William Blake5 in the British neoclassical literature6, but the poet is much ahead of this literary school. It is possible to state that Blake is a romantic poet even if he does not belong to the period called Romanticism. We are dealing with an author who is mostly a dandy7 and who is pointed out by many authors as the most complete artist of his time. Blake, besides being a poet, was a painter and created a unique style not only in the expression but also in the way of making it. He created a painting style known as illuminated printing that consists of engraving a drawing on a copper surface a technique very similar to the watercolor: in both it is almost impossible to touch up any mistake. Examples: Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 1 Figure 1. Pietá. Figure 3. God as an architect. Figure 2. Pegasus. Figure 4. The black dragon. Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 2 Figure 5. Lovers’ vortex. Historical context The England in which William Blake lived was the one in the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. We know that the Industrial Revolution was a movement for change that started in the XVIII century and, according to the historian Eric Hobsbawn, “constitutes the greatest change in history since the remote times when the human being invented agriculture and metallurgy…”8 Although we know that the industrial revolution started, it is difficult to say when it ended, or if it ended9. This revolution was not a revolutionary act in itself but a sequence of factors that led to mechanization, development of technical industrial production and communications. So much so that it was one of the great fomentations for the ascension of capitalism. During this big change the philosophical thought was erected on the Enlightenment. This intellectual movement believes that reasoning was the great solution for society’s problems. It was about reasoning, or better still, through the light of the reasoning that everything was explained. The time in which Blake lived was also marked by an event that changed the course of History: the French Revolution from which the ideals of equality, fraternity and prosperity were disseminated, mainly in Europe, and reverberated in America too. The French Revolution influenced so much the poet that he dedicated one of his books to it: The French Revolution: one poem in seven books. Out of seven books, only one was written. It contains verses of political wor- ding that at first glance seem to convey to the reader all the enchantment that the Revolution generated in the poet. But after the events that followed, it seems that it was not fit for poetry10 anymore. The poetry of this period, mainly in English, had a poet that carried in himself the character of the times not only in his biography but also in the text: Alexander Pope11. According to the reviewer Anthony Burgess12, poetry is not written in the XVIII century’s England without Pope’s rhythmic, aesthetic and spiritual influence. If Pope was the biggest influence in England, in France it was Voltaire. The Brazilian reviewer Antonio Cândido, in his classic work Formation of Brazilian literature, draws our attention to the rationalism boom in the work of three writers: Sade, Bocage and Blake: “It is not to be wondered at that this dynamic century barely enclosed by the Horatian ideal of golden mediocrity bursts here and there in Bocage’s work, in Marquis of Sade’s and Blake’s”13. William Blake is the “burst” that will contribute for the advent of the Romantic poetry and with it the poet’s return to his soul and the questioning of his existence. Religious context Since the XVI century differently from the rest of Europe Catholicism was not England’s formal religion. This English religious reformation started during Henry VIII’s kingdom but it was under Elisabeth I that it was consolidated and instituted as an independent Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 3 religion from Catholicism. The Anglicanism became, then, England’s formal religion. In England there was another important religion: the Calvinist Protestantism. Calvinism was intrinsically linked to businessmen who viewed this religion as possible answers to the questions about God and profit. The historian Antonio Pedro says in his History of Western Civilization: “The capitalistic spirit of the Calvinist religion agreed with the bourgeoisies’ aspirations”14. There was also a third religion in XVIII century’s England: Catholicism. The Roman Apostolic Catholic Church, almost hegemonic in the world, in England was the religion with the fewest number of followers. The historian Eric J. Hobsbawn points out the fact that the Catholic religion was a rural religion followed by the poorest people in England during the Industrial Revolution15. The poet William Blake was born in a Catholic poor family. He was educated and grew up in London’s Catholic poor boroughs. He became a poet in a context where there were no known poets who did not belong at least in appearance to Anglicanism. An example is Pope who was influenced by the Enlightenment but due to patronage declared himself an Anglican. However most of the time he kept himself far from religious questions unless his patron instigated him to treat such subjects. Blake is a poet with no patron. He pays publication with his private funds and follows a faith since childhood but does not agree with it. For any writer in his position it would have been much easier to solve his problem of disagreement with the Catholic faith once “[…] the des-Christianization of man was spread among the educated classes in the end of the XVII century or at the beginning of the XVIII”16. But not for Blake. The poet never doubted the existence of God, not even was able to believe that the misery and sufferings of human beings were divine intention or punishments. The author also could not find answers in the Enlightenment’s pure and simple reasoning. He faced then a serious problem and professor Haroldo de Campos already said that the best poetry is created from serious problems. Thus we view William Blake’s poetry as the search for understanding God in its possible relationship with human beings in their different stages in life. The next part of this work is dedicated to a bibliographic return to the poet through such interpretation. William Blake (1757 – 1827) The first book published by William Blake was Poetical sketches which was sponsored by some friends of his and had a small distribution in England. Blake’s first ideas for poems appeared in this book where he designs his linguistic style that is going to be characterized by a language very much close to people, in a very musical poetic rhythm and with a questioning thematic of the institutions instilled with the idea of fugere urbem17. Later on he dedicates himself to the Book of Thel, a brief poem in which his own mythology and symbology start to appear. At the time he undertakes a unique literary work. It is a book permeated by engravings and illuminated printings that integrate the poetic text. It is Songs of Innocence, a book of a very limited edition because it was a handicraft fully made by the author and his wife. Five years later Blake goes back to the same process and creates Songs of Experience which is inseparable from Songs of Innocence. As we said before, it seems that both books integrate each other by weaving a set of paradoxes and antitheses using a language with a popular rhythm and cadence. Other works by the poet that are relevant for this work are: Auguries of Innocence, The French Revolution, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and his last book Jerusalem Invocation. The poet William Blake will be reference and enigma for several generations of artists. Poets so far apart in space and time such as John Keats, William Wordsworth, Dylan Thomas and Jim Morrison dedicated themselves and were influenced by Blake. Even great English prose writers were influenced by his work. Today according to many literature historians it is one of the greatest in its language being compared in importance to William Shakespeare. The Poem The poem examined is The Lamb. Although we found several translations, we decided to use one made by us. It follows the poem and our translation: Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 4 The Lamb Little Lamb, who made thee? Does thou know who made thee? Gave thee life, and bid thee feed, By the stream and o’er the mead; Gave thee clothing of delight, Softest clothing, woolly, bright; Gave thee such a tender voice, Making all the vales rejoice? Little Lamb, who made thee? Does thou know who made thee? Little Lamb, I’ll tell thee, Little Lamb, I’ll tell thee. He is called by thy name, For He calls Himself a Lamb He is meek, and He is mild, He became a little child. I’m a child, and thou a lamb, We are called by His name. Little Lamb, God bless thee! Little Lamb, God bless thee! O cordeiro Pequeno cordeiro, quem te criou? Tu não saberias quem te criou? Deu-te vida e alimento mandado por todas as campinas, por todos os regatos Ofertou vestes ao teu prazer, Vestes finas! de pura lã a resplandecer, Deu-te suavidade à voz. Para alegrar da montante à foz? Pequeno cordeiro, quem te criou? Tu não saberias quem te criou? Pequeno cordeiro, te contarei Pequeno cordeiro, te contarei Pelo Mesmo nome Ele é invocado O próprio Cordeiro é consagrado Muito afável, Ele é manso, Tornou-se uma pequena criança Eu uma criança, tu um cordeiro, Por um único nome somos chamados. Pequeno Cordeiro, Deus te abençoe! Pequeno Cordeiro, Deus te abençoe! Formal aspect of the poem The poem The Lamb consists of twenty verses that are divided into three stanzas being two of eight verses and the third and last of four verses. Its metrics alternates six or seven syllables permeating a rigorous scale of rhymes disposed as follows: AABBCCDD/ AAAAEEFF/EEAA. As to the rhythm, we see in the two first stanzas that the first two and the last two verses are trochees18 which are grouped in three sounds, and in the middle stanzas are trochaic tetrameter; only in the last stanza we see a rhythmic unity made by the three trochees. This poetic scale is very similar to the popular poetry with didactic character. In Portuguese language the equivalent verse can be the bigger roundel with trochaic stress19. In our translation we tried to concentrate on the contents because the formal scale was minimized due to linguistic differences. However it is essential to point out the relationship between form and contents in the examined text once it is a sequence of metric, rhythm and popular rhymes, facilitating the memorization of the text by the reader and giving it a teaching character. Analysis and interpretation of the poem In the poem contexture we have an important reference to the Bible: “The lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1,29). In this gospel Christ is since the beginning presented as the one who will save humankind through his sacrifice. John’s gospel presents a Christ who is aware of his mission, convinced by it and agreeable to it. Blake uses again the Biblical text in a clear reference to the message that the lamb will save the world. He gives a new meaning and interprets the Biblical passage in a time analysis that imprints his religiosity and gives his own Christ’s symbolization. Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 5 Thus, we have a game that is set up as follows: The lamb is in the poem’s title and according to the entry in Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant’s dictionary, it is the archetypal symbol present in three great religions: Christianism, Judaism and Islamism, marked by a similar meaning in all of them as we can see below: […] appears in its immaculate and glorious whiteness as a spring transfiguration; it incarnates the triumph of victory’s renewal, the continuous renewal of life over death. It is precisely this archetypal function that makes the lamb par excellence the propitious victim, the one that has to be sacrificed in order to ensure its own salvation20. The poem is not limited to praise the lamb; it is a didactic-reflective poem in conformity with the standard Anglican catechism at the time. In a framework permeated by rhetorical questions William Blake builds a lamb that is three without being threefold meaning trinity, but three starting from one and not three that are one. The first rhetoric question is asked by the poetic subject21 to the lamb (animal): Little Lamb, who made thee? Does thou know who made thee? After asking the character, the poetic subject makes a list of qualifying actions of this not revealed creator yet (verses 3 to 8). The subject goes back to the same question in verses 9 and 10. In the first and in the beginning of the second stanza, we have just the poetic subject’s discourse about the creation of the lamb. Starting from the third verse of the second stanza we find the revelation of the poetic subject, a revelation that is very much dramatic and that happens as follows: Little Lamb, I’ll tell thee. Little Lamb, I’ll tell thee. We notice in these verses a means to keep the reader’s attention: to create a matter-of-fact suspense in the text which is soon broken when we find the use of capital letters for the pronoun in verse 13: For He calls Himself a Lamb The capital letter is used here as also in the English text. An important point is the regress of the Lamb that being consecrated leads us to the idea of immolation and innocence. The Lamb represents the childhood, both elements of innocence not tainted by society yet. These elements go back to nature, stressing the poet’s romantic character marked by the return to the pagan world22. We have then three independent elements that are part of a whole. Blake’s poetry is highly marked by the idea that God is an entity as much as the human being. In the examined poem we have three elements that converge into one only. The poetic subject being a lamb as much as Christ, the lamb is likewise a lamb that is a lamb. Therefore there is a metonymy of Nature becoming manifest the idea of immanency. In the finishing stanza we have a refrain that seems to join the three elements: poetic subject, lamb and Christ in just one lamb, but the poetic subject and Christ are kept individually. The Lamb and the Tiger We could not leave out the famous poem The Tiger, a similar text that is five years older than the poem we are examining. They complement each other because in the first we have the exaltation of innocence created by God that is part of nature; in the second we have God creating wickedness and inserting it in nature making it immanent too. Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 6 The Tiger (1794) O Tigre Tiger! Tiger! burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Could frame thy fearful symmetry? Tigre, Tigre, viva chama Que as florestas da noite inflama. Que olho ou mão imortal podia Traçar-te a horrível simetria? In what distant deeps or skies Burnt the fire of thine eyes? On what wings dare he aspire? What the hand dare seize the fire? Em que abismo ou céu longe ardeu O fogo dos olhos teus? Com que asas ousou ele o vôo? Que mão ousou pegar o fogo? And what shoulder, and what art. Could twist the sinews of thy heart? And when thy heart began to beat, What dread hand? And what dread feet? Que arte & braço pôde então Torcer-te as fibras do coração? Quando ele já estava batendo Que mão e que pés horrendos? What the hammer? What the chain? In what furnace was thy brain? What the anvil? What dread grasp Dare its deadly terrors clasp? Que cadeia? Que martelo, Que fornalha teve o teu cérebro? Que bigorna? Que tenaz Pegou-lhe os horrores mortais? When the stars threw down their spears, And watered heaven with their tears, Did he smile his work to see? Did he who made the Lamb make thee? Quando os astros alancearam O céu e em pranto o banharam, Sorriu ele ao ver seu feito? Fez-te quem fez o Cordeiro? Tiger! Tiger! Burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Dare frame thy fearful symmetry? Tigre, Tigre, viva chama Que as florestas da noite inflama, Que olho ou imortal mão ousaria Traçar-te a horrível simetria Tradução de José Paulo Paes Bibliography ARANTES, José Antonio. An obscure and brilliant prophet. In: Cadernos entre livros: Outlook of British literature. São Paulo, Duetto, 2007. v. 1. SACRED BIBLE. Pastoral Edition. São Paulo, Paulus, [s.d.] SACRED BIBLE TEB. São Paulo, Loyola-Paulinas, 1995. BURGESS, A. British literature. Básica Universitária, [s.d.] CÂNDIDO, Antonio. The analytical study of a poem. 4th edition. São Paulo, FFLCH-Humanitas, [s.d.] ______. Formation of Brazilian literature. 5th edition. São Paulo-Belo Horizonte: Editora Edusp-Itatiaia, [s.d.]. CHEVALIER, J. & GHEERBRANT, Dictionary of symbols. 18th edition. Rio de Janeiro, José Olympio Editora, 2003. HOBSBAWN, Eric J. The era of revolutions. Translated by Maria Tereza Lopez Teixeira and Marcos Penchel. São Paulo, Paz e Terra, 1998. LYRA, Pedro. Concept of poetry. 2nd edition. São Paulo, Ática, [s.d.]. Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 7 MAGALHÃES, A. Carlos de Melo. Religion and literature: perspectives of dialogue between Sciences of Religion and literature. Religião & Cultura, v. III, n. 6, July-December 2004. PEDRO, Antonio & LIMA, Lizânias de Souza. History of Western civilization. São Paulo, FTD, 2005. REVELATIONS. Part III of III. Magazine ORIGEM 3, June 2002. SAINT AUGUSTINE. Confessions. São Paulo, Paulus, 1984. SANTOS, Clarissa Soares dos. “Appraisal of poetry translation: an objective analysis of the translations of The Lamb, by William Blake”. Available in http://www.maxwell.lambda.ele.puc-rio.br/cgi-in/PRG_0599.EXE/9364. PDF?NrOcoSis=28849&CdLinPrg=pt> Access in 06/02/2007. 7 VIZIOLI, P. William Blake: selected poems and prose. São Paulo, Nova Alexandria,1993. <http://asms.k12.ar.us/classes/humanities/britlit/97-98/ blake/POEMS.HTM#LAMB>. Access in 06/02/2007. <http://www.universalteacher.org.uk/poetry/blake. htm#lamb>. Access in 06/02/2007. Notes * ** 1 2 3 4 5 6 Attending her Master’s degree in Religion Sciences – PUCSP. Attending his Master’s degree in Religion Sciences – PUCSP. CÂNDIDO, Antonio. The analytical study of the poem. LYRA, Pedro. Concept of poetry. CÂNDIDO, Antonio. Op. cit. p. 27. MAGALHÃES, Antonio Carlos de Melo. Religion and literature: perspectives of dialogue between Sciences of Religion and Literature. William Blake: English engraver and poet who was born in 1757 and died in 1827. He was of humble origin and most of what he learned was by himself; he spent just a short period studying painting at the Royal Academy of Arts. He was very much criticized in his time and was a complete publishing failure in the XVIII century’s England. With the Romanticism Blake becomes a reference for poets mainly those who adhered to the Byron’s aesthetics or ‘mal-dusiècle’. Among his important readers we can cite: George Gordon Byron (England), Arthur Rimbaud (France), Almeida Garret (Portugal) and Álvares de Azevedo (Brazil). Neoclassicism or Arcadian is a literary style that dominates several countries during the second half of the XVIII century and the first quarter of 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 XIX century. This literary school is very much influenced by the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, the French Revolution and the United States Independence. The neoclassicism appraises a return to the classical literature emulating it as a model for enlightenment and poetic correctness; in the neoclassicism the Greek-Latin ideals are disseminated linked to the philosophical thought at the time. An important feature was the denial of all religions in an anthropocentrism that for the neoclassical artist would result in man’s complete freedom. Important men in the field were: Alexander Pope (England), Marchioness of Alorna (Portugal/ France) and Cláudio Manuel da Costa (Brazil). According to the French poet Charles Baudelaire, dandy is the opposite of flaneur. These are two essential concepts for the reading of modern arts. The dandy is the individual who as an artist makes of himself a work of art. An example is the novelist and playwright Oscar Wilde, known not only for his literature but also for his extravagant way of life. The flaneur is the individual who as an artist is concerned with his art above himself; as an example we have the expressionists who in many cases not even signed their works. William Blake, for example, coming historically before Baudelaire’s concepts, cannot be defined as a dandy but in his own way he fits in the concept. HOBSBAWN, Eric J. The era of the revolutions. HOBSBAWN, Eric. J. Op. cit. ARANTES, José Antonio. An obscure and brilliant prophet. Alexander Pope (1688 – 1744): the greatest rationalist English poet. His family was catholic but he abandoned his religion and wrote the book Essay on man, where he tries to explain God and existential questions in a rational way. It is Pope the poet that elects and creates followers. Main works: Ode on solitude and Essay on man. BURGESS, Anthony. British literature. CÂNDIDO, Antonio. Formation of Brazilian literature. PEDRO, Antonio. LIMA, Lizânias de Souza. History of Western Civilization. See HOBSBAWN, Eric J. Op. cit. pages 239-255. Idem, ib. p. 240. In the neoclassicism there are three words of command for the poet: carpe diem: seize the day; inutilia truncate: dismiss uselessness; fugere urbem: flee the town. Trochee: a resource for rhythmic building that means a symmetric use of one long syllable followed by one short syllable; in this case the 8 19 20 21 22 poet uses this resource mostly in groups of three syllables. It is used in the “cordel” poetry. CHEVALIER, J.; GHEERBRANT, A. Dictionary of Symbols, p. 287. A character that speaks in poetry when it is not lyric-love, because then we have an “I” that is lyric. Perhaps the main feature of the pagan religiosity is the divine immanence, that is, it is in the Nature itself (what includes human beings) and manifests itself through its phenomena. www.wikipedia.com accessed in 07/27/07. Ciberteologia - Journal of Theology & Culture – Year II, n. 14 9