A Basic Overview of Strict Scrutiny and Mid

advertisement

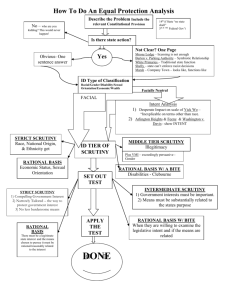

A Basic Overview of Strict Scrutiny and Mid-level Scrutiny Tests as Applied to Issues of Speech and Press The guarantees of free speech and press provided by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution are not absolute. Courts continually are faced with balancing freedom of speech and freedom of the press against other personal rights or interests of society. In dealing with these issues, the U.S. Supreme Court has developed a number of tests to interpret the First Amendment. Two used in media cases are the strict scrutiny test and the mid-level scrutiny test; the latter more commonly is referred to as the “O'Brien Test.” Strict scrutiny is used when restrictions on speech or press are content-based, that is, the reason for regulation is based on the content of a message. When reviewing content-based restrictions, the Court asks two questions: 1. Does the regulation further a compelling governmental interest? 2. Are the means used narrowly tailored to accomplish that governmental interest? The key phrases in a strict scrutiny review are compelling governmental interest and means that are narrowly tailored. Speech and press cases dealing with content-based restrictions seldom are decided in favor of the government. A 1992 case from Tennessee, however, not only illustrates how the Court uses the strict scrutiny test, but also is a case in which the Court ruled in favor of content-based restriction on speech. Burson v. Freeman, 504 U.S. 191 (1992) involved a Tennessee state law that prohibited election campaigning within 100 feet of a building housing a polling place. “Within the appropriate boundary [100 feet from the entrances]…the display of campaign posters, signs or other campaign materials, distribution of campaign materials, and solicitation of votes for or against any person or political party or position on a question are prohibited.” Mary Rebecca Freeman was the treasurer for a city council candidate in 1987 when she challenged the Tennessee statute. A county court in Nashville ruled against her, but the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled in her favor. The state (represented by Tennessee Attorney General Charles Burson) appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In the 1992 ruling, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote that the case required the use of strict scrutiny because it involved a “content-based restriction on political speech….” Blackmun continued: “To survive strict scrutiny, however, a State must do more than assert a compelling state interest - it must demonstrate that its law is necessary to serve the asserted interest. While we readily 2 acknowledge that a law rarely survives such scrutiny, an examination of the evolution of election reform, both in this country and abroad, demonstrates the necessity of restricted areas in or around polling places.” “(T)he link between ballot secrecy and some restricted zone surrounding the voting area is not merely timing - it is common sense. The only way to preserve the secrecy of the ballot is to limit access to the area around the voter. Accordingly, we hold that some restricted zone around the voting area is necessary to secure the State's compelling interest.” (Emphasis added) After establishing that the state did, in fact, have a compelling interest, Justice Blackmun very quickly addressed the issue of whether the 100-feet limit was narrowly tailored: “It is sufficient to say that, in establishing a 100-foot boundary, Tennessee is on the constitutional side of the line. In conclusion, we reaffirm that it is the rare case in which we have held that a law survives strict scrutiny. This, however, is such a rare case.” Mid-level scrutiny is used when restrictions on speech or press are content-neutral, that is, the reason for regulation is NOT connected to content but focuses on means of transmission. This test has come to be known as the “O’Brien Test” because the Court used it in 1968 in the case of U.S. v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968). This is another First Amendment case from the time of the War in Vietnam. David O'Brien and three companions were arrested in 1966 for violating the Universal Military Training and Service Act, as amended, after burning their Selective Service registration certificates, more commonly referred to at that time as their draft cards. O'Brien claimed the law abridged his free speech rights and that he was arrested because he opposed the war. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, upheld O’Brien’s conviction. Chief Justice Earl Warren issued the majority opinion, writing: “We think it clear that a government regulation is sufficiently justified if it is within the constitutional power of the Government; if it furthers an important or substantial governmental interest; if the governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression; and if the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedoms is no greater than is essential to the furtherance of that interest. We find that the 1965 Amendment to…the Universal Military Training and Service Act meets all of these requirements, and consequently that O'Brien can be constitutionally convicted for violating it.” To review, if government regulation affects conduct with both speech and non-speech components, and if regulation incidentally restricts expression, a law is still valid if it meets the four-part “O'Brien Test.” The four parts are: 1. Congress has the constitutional authority to enact the law. 2. The regulation furthers a substantial governmental interest. 3. That government interest is unrelated to suppression of free expression. 4. The restrictions imposed are no greater than necessary to further governmental interest. When comparing strict scrutiny and mid-level scrutiny, note that the O’Brien Test calls for furthering a substantial governmental interest. Strict scrutiny requires a compelling interest. 3 Also, O’Brien requires that restrictions on speech or press be no greater than necessary. Strict scrutiny requires restrictions that are narrowly tailored to meet the government’s interest. An example of how a case can hinge on the type of test used is the case of Turner Broadcasting v. FCC. This is a case decided in 1994, 512 U.S. 622 (1994), and again in 1997, 520 U.S. 180 (1997), and involves a part of a law that requires cable television systems to carry the signals of all over the air broadcast TV stations in a market that request to be carried. Turner challenged this “must carry” law, claiming it violated its First Amendment rights. The Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the particular law focused on the means of transmission, so it was a content-neutral regulation. Dissenters argued that the law was content-based—they said that the specific type of stations, that is, over the air broadcast stations—made the law content-based and required it to be reviewed with strict scrutiny. The majority, however, ruled that the law furthered a substantial government interest and that the restriction was no greater than necessary to further that interest. If the dissenters could have swayed one vote, the majority would have been required to look at the “must carry” law with strict scrutiny. As Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (joined by Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Ginsburg) wrote in her dissent: “The net result appears to be that five Justices of this Court do not view must carry as a narrowly tailored means of serving a substantial governmental interest in preventing anticompetitive behavior; and that five Justices of this Court do see the significance of the content of over the air programming to the Government's and appellees' efforts to defend the law. Under these circumstances, the must carry provisions should be subject to strict scrutiny, which they surely fail.” One swing vote (Justice Breyer) determined which test was used, and one swing vote determined how the court ruled. © 2013 Ball State University