14 Chemical Kinetics

advertisement

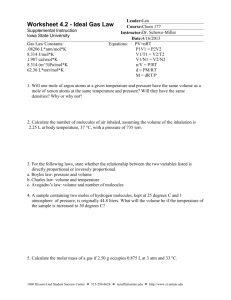

14 Chemical Kinetics Visualizing Concepts 14.1 14.4 (a) X is a product, because its concentration increases with time. (b) The average rate of reaction between any two points on the graph is the slope of the line connecting the two points. The average rate is greater between points 1 and 2 than between points 2 and 3 because they are different stages in the overall process. Points 1 and 2 are earlier in the reaction when more reactants are available, so the rate of formation of products is greater. As reactants are used up, the rate of X production decreases, and the average rate between points 2 and 3 is smaller. Analyze. Given three mixtures and the order of reaction in each reactant, determine which mixture will have the fastest initial rate. Plan. Write the rate law. Count the number of reactant molecules in each container. The three containers have equal volumes and total numbers of molecules. Use the molecule count as a measure of concentration of NO and O2. Calculate the initial rate for each container and compare. Solve. Rate = k[NO]2[O2]; rate is proportional to [NO]2[O2] Container [NO] [O2] [NO]2[O2] ∝ rate (1) 5 4 100 (2) 7 2 98 (3) 3 6 54 The relative rates in containers (1) and (2) are very similar, with (1) having the slightly faster initial rate. 14.6 Analyze. Given concentrations of reactants and products at two times, as represented in the diagram, find t1/2 for this first-order reaction. Plan. For a first order reaction, t1/2 = 0.693/k; t1/2 depends only on k. Use Equation [14.12] to solve for k. Solve. (a) Since reactants and products are in the same container, use number of particles as a measure of concentration. The red dots are reactant A, and the blue are product B. [A]0 = 8, [A]30 = 2, t = 30 min. ln = –kt. ln(2/8) = –k(30 min); 378 = k; 14 Chemical Kinetics Solutions to Exercises k = 0.046210 = 0.0462 min−1 t1/2 = 0.693/k = 0.693/0.046210 = 15 min By examination, [A]0 = 8, [A]30 = 2. After 1 half-life, [A] = 4; after a second halflife, [A] = 2. Thirty minutes represents exactly 2 half-lives, so t1/2 = 15 min. [This is more straightforward than the calculation, but a less general method.] (b) 14.10 After 4 half-lives, [A]t = [A]0 × 1/2 × 1/2 × 1/2 × 1/2 = [A]0/16. In general, after n half-lives, [A] = [A]0/2n. This is the profile of a two-step mechanism, A → B and B → C. There is one intermediate, B. Because there are two energy maxima, there are two transition states. The B → C step is faster, because its activation energy is smaller. The reaction is exothermic because the energy of the products is lower than the energy of the reactants. Reaction Rates 14.13 14.15 (a) Reaction rate is the change in the amount of products or reactants in a given amount of time; it is the speed of a chemical reaction. (b) Rates depend on concentration of reactants, surface area of reactants, temperature and presence of catalyst. (c) The stoichiometry of the reaction (mole ratios of reactants and products) must be known to relate rate of disappearance of reactants to rate of appearance of products. Analyze/Plan. Given mol A at a series of times in minutes, calculate mol B produced, molarity of A at each time, change in M of A at each 10 min interval, and ΔM A/s. For this reaction, mol B produced equals mol A consumed. M of A or [A] = mol A/0.100 L. The average rate of disappearance of A for each 10 minute interval is Solve. Time (min) Mol A (a) Mol B [A] 0 0.065 0.000 0.65 10 0.051 0.014 0.51 −0.14 2.3 × 10 20 0.042 0.023 0.42 −0.09 2 × 10 30 0.036 0.029 0.36 −0.06 1 × 10 40 0.031 0.034 0.31 −0.05 0.8 × 10 (c) 379 Δ[A] (b) Rate −(Δ[A]/s) –4 –4 –4 –4 14 Chemical Kinetics 14.17 (a) Solutions to Exercises Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercises 14.1 and 14.2. Time (sec) Time Interval (sec) Concentration (M) 0 Solve. ΔM Rate (M/s) 0.0165 –7 2,000 2,000 0.0110 –0.0055 28 × 10 5,000 3,000 0.00591 –0.0051 17 × 10 8,000 3,000 0.00314 –0.00277 9.23 × 10 12,000 4,000 0.00137 –0.00177 4.43 × 10 15,000 3,000 0.00074 –0.00063 2.1 × 10 (b) –7 –7 –7 –7 From the slopes of the lines in the figure at right, the rates are: at 5000 s, 12 × 10−7 M/s; at 8000 s, 5.8 × 10−7 M/s 14.19 Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercise 14.3. (a) –Δ[H2O2]/Δt = Δ[H2]/Δt = Δ[O2]/Δt (b) –Δ[N2O]/2Δt = Δ[N2]/2Δt = Δ[O2]/Δt Solve. –Δ[N2O]/Δt = Δ[N2]/Δt = 2Δ[O2]/Δt (c) –Δ[N2]/Δt = Δ[NH3]/2Δt; –Δ[H2]/3Δt = Δ[NH3]/2Δt –2Δ[N2]/Δt = Δ[NH3]/Δt; –Δ[H2]/Δt = 3Δ[NH3]/2Δt 14.21 Analyze/Plan. Use Equation [14.4] to relate the rate of disappearance of reactants to the rate of appearance of products. Use this relationship to calculate desired quantities. Solve. (a) Δ[H2O]/2Δt = –Δ[H2]/2Δt = –Δ[O2]/Δt H2 is burning, –Δ[H2]/Δt = 0.85 mol/s O2 is consumed, –Δ[O2]/Δt = –Δ[H2]/2Δt = 0.85 mol/s/2 = 0.43 mol/s 380 14 Chemical Kinetics Solutions to Exercises H2O is produced, +Δ[H2O]/Δt = –Δ[H2]/Δt = 0.85 mol/s (b) The change in total pressure is the sum of the changes of each partial pressure. NO and Cl2 are disappearing and NOCl is appearing. –ΔPNO/Δt = –23 torr/min +ΔPNOCl/Δt = –ΔPNO/Δt = +23 torr/min ΔPT/Δt = –23 torr/min – 12 torr/min + 23 torr/min = –12 torr/min Rate Laws 14.23 Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercises 14.4 and 14.5. Solve. (a) If [A] is doubled, there will be no change in the rate or the rate constant. The overall rate is unchanged because [A] does not appear in the rate law; the rate constant changes only with a change in temperature. (b) The reaction is zero order in A, second order in B and second order overall. (c) 14.25 Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercise 14.4. –3 Solve. –1 (a) rate = k[N2O5] = 4.82 × 10 s [N2O5] (b) rate = 4.82 × 10 s (0.0240 M) = 1.16 × 10 M/s (c) rate = 4.82 × 10 s (0.0480 M) = 2.31 × 10 M/s –3 –1 –4 –3 –1 –4 When the concentration of N2O5 doubles, the rate of the reaction doubles. 14.27 Analyze/Plan. Write the rate law and rearrange to solve for k. Use the given data to calculate k, including units. Solve. (a, b) rate = k[CH3Br][OH−]; k = (c) 14.29 – – Since the rate law is first order in [OH ], if [OH ] is tripled, the rate triples. Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercise 14.6. – Solve. – (a) From the data given, when [OCl ] doubles, rate doubles. When [I ] doubles, rate – – – – doubles. The reaction is first order in both [OCl ] and [I ]. rate = [OCl ][I ] (b) Using the first set of data: 381 14 Chemical Kinetics Solutions to Exercises (c) 14.31 Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercise 14.6 to deduce the rate law. Rearrange the rate law to solve for k and deduce units. Calculate a k value for each set of concentrations and then average the three values. Solve. (a) Doubling [NH3] while holding [BF3] constant doubles the rate (experiments 1 and 2). Doubling [BF3] while holding [NH3] constant doubles the rate (experiments 4 and 5). Thus, the reaction is first order in both BF3 and NH3; rate = k[BF3][NH3]. (b) The reaction is second order overall. (c) From experiment 1: (Any of the five sets of initial concentrations and rates could be used to calculate –1 –1 the rate constant k. The average of these 5 values is kavg = 3.408 = 3.41 M s ) (d) 14.33 –1 –1 rate = 3.41 M s (0.100 M)(0.500 M) = 0.1704 = 0.170 M /s Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercise 4.6 to deduce the rate law. Rearrange the rate law to solve for k and deduce units. Calculate a k value for each set of concentrations and then average the three values. Solve. (a) Increasing [NO] by a factor of 2.5 while holding [Br2] constant (experiments 1 2 and 2) increases the rate by a factor 6.25 or (2.5) . Increasing [Br2] by a factor of 2.5 while holding [NO] constant increases the rate by a factor of 2.5. The rate law for 2 the appearance of NOBr is: rate = Δ[NOBr]/Δt = k[NO] [Br2]. (b) From experiment 1: 2 4 4 k2 = 150/(0.25) (0.20) = 1.20 × 10 = 1.2 × 10 M 2 4 4 –2 4 4 –2 k3 = 60/(0.10) (0.50) = 1.20 × 10 = 1.2 × 10 M 2 k4 = 735/(0.35) (0.50) = 1.2 × 10 = 1.2 × 10 M 4 –2 4 4 4 s s s –1 –1 –1 4 kavg = (1.2 × 10 + 1.2 × 10 + 1.2 × 10 + 1.2 × 10 )/4 = 1.2 × 10 M –2 s –1 (c) Use the reaction stoichiometry and Equation 14.4 to relate the designated rates. Δ[NOBr]/2Δt = –Δ[Br2]/Δt; the rate of disappearance of Br2 is half the rate of appearance of NOBr. (d) Note that the data are given in terms of appearance of NOBr. = 8.4 M/s 382 14 Chemical Kinetics Solutions to Exercises Change of Concentration with Time 14.35 14.37 (a) [A]0 is the molar concentration of reactant A at time zero, the initial concentration of A. [A]t is the molar concentration of reactant A at time t. t1/2 is the time required to reduce [A]0 by a factor of 2, the time when [A]t = [A]0/2. k is the rate constant for a particular reaction. k is independent of reactant concentration but varies with reaction temperature. (b) A graph of ln[A] vs time yields a straight line for a first-order reaction. Analyze/Plan. The half-life of a first-order reaction depends only on the rate constant, t1/2 = 0.693/k. Use this relationship to calculate k for a given t1/2, and, at a different temperature, t1/2 given k. Solve. (a) 5 t1/2 = 2.3 × 10 s; t1/2 = 0.693/k, k = 0.693/t1/2 5 –6 k = 0.693/2.3 × 10 s = 3.0 × 10 s (b) 14.39 –5 –1 –1 –5 –1 4 4 k = 2.2 × 10 s . t1/2 = 0.693/2.2 × 10 s = 3.15 × 10 = 3.2 × 10 s Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercise 14.7. In this reaction, pressure is a measure of concentration. In (a) we are given k, [A]0, t and asked to find [A]t, using Equation [14.13], the integrated form of the first-order rate law. In (b), [At] = 0.1[A0], find t. Solve. (a) lnPt = –kt + lnP0; P0 = 375 torr; t = 65 s –2 –1 lnP65 = –4.5 × 10 s (65) + ln(375) = –2.925 + 5.927 = 3.002 P65 = 20.12 = 20 torr (b) Pt = 0.10 P0; ln(Pt/P0) = –kt ln(0.10 P0/P0) = –kt, ln(0.10) = –kt; –ln(0.10)/k = t –2 –1 t = –(–2.303)/4.5 × 10 s = 51.2 = 51 s Check. From part (a), the pressure at 65 s is 20 torr, Pt ~ 0.05 P0. In part (b) we calculate the time where Pt = 0.10 P0 to be 51 s. This time should be smaller than 65 s, and it is. Data and results in the two parts are consistent. 14.41 Analyze/Plan. Given reaction order, various values for t and Pt, find the rate constant for the reaction at this temperature. For a first-order reaction, a graph of lnP vs t is linear with as slope of –k. Solve. t(s) ln 0 1.000 0 2500 0.947 –0.0545 5000 0.895 –0.111 7500 0.848 –0.165 383 14 Chemical Kinetics 10000 0.803 Solutions to Exercises –0.219 Graph ln vs. time. (Pressure is a satisfactory unit for a gas, since the concentra–5 –1 tion in moles/liter is proportional to P.) The graph is linear with slope –2.19 × 10 s –5 –1 as shown on the figure. The rate constant k = –slope = 2.19 × 10 s . 14.43 Analyze/Plan. Given: mol A, t. Change mol to M at various times. Make both first- and second-order plots to see which is linear. Solve. (a) time(min) mol A [A] (M) ln[A] 1/mol A 0 0.065 0.65 –0.43 1.5 10 0.051 0.51 –0.67 2.0 20 0.042 0.42 –0.87 2.4 30 0.036 0.36 –1.02 2.8 40 0.031 0.31 –1.17 3.2 The plot of 1/[A] vs time is linear, so the reaction is second-order in [A]. (b) For a second-order reaction, a plot of 1/[A] vs. t is linear with slope k. k = slope = (3.2 – 2.0) M –1 / 30 min = 0.040 M (The best fit to the line yields slope = 0.042 M (c) t1/2 = 1/k[A]0 = 1/(0.040 M –1 –1 –1 min –1 –1 min .) –1 min )(0.65 M) = 38.46 = 38 min (Using the “best-fit” slope, t1/2 = 37 min.) 14.45 Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Solution 14.43. Make both first and second order plots to see which is linear. Solve. (a) time(s) [NO2](M) ln[NO2] 1/[NO2] 0.0 0.100 –2.303 10.0 5.0 0.017 –4.08 59 10.0 0.0090 –4.71 110 15.0 0.0062 –5.08 160 384 14 Chemical Kinetics 20.0 0.0047 Solutions to Exercises –5.36 210 The plot of 1/[NO2] vs time is linear, so the reaction is second order in NO2. (b) –1 –1 –1 The slope of the line is (210 – 59) M / 15.0 s = 10.07 = 10 M s = k. (The slope –1 –1 of the best-fit line is 10.02 = 10 M s .) Temperature and Rate 14.47 14.49 (a) The energy of the collision and the orientation of the molecules when they collide determine whether a reaction will occur. (b) According to the kinetic-molecular theory (Chapter 10), the higher the temperature, the greater the speed and kinetic energy of the molecules. Therefore, at a higher temperature, there are more total collisions and each collision is more energetic. Analyze/Plan. Given the temperature and energy, use Equation [14.18] to calculate the fraction of Ar atoms that have at least this energy. Solve. f=e –3.0070 = 4.9 × 10 –2 At 400 K, approximately 1 out of 20 molecules has this kinetic energy. 14.51 Analyze/Plan. Use the definitions of activation energy (Emax – Ereact) and ΔE (Eprod – Ereact) to sketch the graph and calculate Ea for the reverse reaction. Solve. (a) (b) 385 Ea(reverse) = 73 kJ 14 Chemical Kinetics 14.53 14.55 Solutions to Exercises Assuming all collision factors (A) to be the same, reaction rate depends only on Ea; it is independent of ΔE. Based on the magnitude of Ea, reaction (b) is fastest and reaction (c) is slowest. Analyze/Plan. Given k1, at T1, calculate k2 at T2. Change T to Kelvins, then use the Equation [14.21] to calculate k2. Solve. –2 –1 T1 = 20°C + 273 = 293 K; T2 = 60°C + 273 = 333 K; k1 = 2.75 × 10 s (a) (b) 14.57 Analyze/Plan. Follow the logic in Sample Exercise 14.11. Solve. 3 k ln k T(K) 1/T(× 10 ) 0.0521 –2.955 288 3.47 0.101 –2.293 298 3.36 0.184 –1.693 308 3.25 0.332 –1.103 318 3.14 3 The slope, –5.71 × 10 , equals –Ea/R. Thus, 3 Ea = 5.71 × 10 × 8.314 J/mol = 47.5 kJ/mol. 14.59 Analyze/Plan. Given Ea, find the ratio of rates for a reaction at two temperatures. Assuming initial concentrations are the same at the two temperatures, the ratio of rates will be the ratio of rate constants, k1/k2. Use Equation [14.21] to calculate this ratio. Solve. T1 = 50°C + 273 = 323 K; T2 = 0°C + 273 = 273 K 3 –4 ln (k1/k2) = 7.902 × 10 (5.670 × 10 ) = 4.481 = 4.5; k1/k2 = 88.3 = 9 × 10 1 The reaction will occur 90 times faster at 50°C, assuming equal initial concentrations. Reaction Mechanisms 14.61 (a) An elementary reaction is a process that occurs in a single event; the order is given by the coefficients in the balanced equation for the reaction. 386 14 Chemical Kinetics 14.63 14.65 Solutions to Exercises (b) A unimolecular elementary reaction involves only one reactant molecule; the activated complex is derived from a single molecule. A bimolecular elementary reaction involves two reactant molecules in the activated complex and the overall process. (c) A reaction mechanism is a series of elementary reactions that describe how an overall reaction occurs and explain the experimentally determined rate law. Analyze/Plan. Elementary reactions occur as a single step, so the molecularity is determined by the number of reactant molecules; the rate law reflects reactant stoichiometry. Solve. (a) unimolecular, rate = k[Cl2] (b) bimolecular, rate = k[OCl ][H2O] (c) bimolecular, rate = k[NO][Cl2] – Analyze/Plan. Use the definitions of the terms ‘intermediate’ and ‘exothermic’, along with the characteristics of reaction profiles, to answer the questions. Solve. This is a three-step mechanism, A → B, B → C, and C → D. 14.67 (a) There are 2 intermediates, B and C. (b) There are 3 energy maxima in the reaction profile, so there are 3 transition states. (c) Step C → D has the lowest activation energy, so it is fastest. (d) The energy of D is slightly greater than the energy of A, so the overall reaction is endothermic. (a) (b) Intermediates are produced and consumed during reaction. HI is the intermediate. (c) Follow the logic in Sample Exercise 14.13. First step: rate = k1[H2][ICl] Second step: rate = k2[HI][ICl] (d) 14.69 The slow step determines the rate law for the overall reaction. If the first step is slow, the observed rate law is: rate = k[H2][HCl]. Analyze/Plan. Given a proposed mechanism and an observed rate law, determine which step is rate determining. Solve. (a) If the first step is slow, the observed rate law is the rate law for this step. rate = k[NO][Cl2] (b) Since the observed rate law is second-order in [NO], the second step must be slow relative to the first step; the second step is rate determining. 387 14 Chemical Kinetics Solutions to Exercises Catalysis 14.71 14.73 14.75 (a) A catalyst increases the rate of reaction by decreasing the activation energy, Ea, or increasing the frequency factor A. Lowering the activation energy is more common and more dramatic. (b) A homogeneous catalyst is in the same phase as the reactants; a heterogeneous catalyst is in a different phase and is usually a solid. (a) (b) NO2(g) is a catalyst because it is consumed and then reproduced in the reaction sequence. (NO(g) is an intermediate because it is produced and then consumed.) (c) Since NO2 is in the same state as the other reactants, this is homogeneous catalysis. (a) Use of chemically stable supports such as alumina and silica makes it possible to obtain very large surface areas per unit mass of the precious metal catalyst. This is so because the metal can be deposited in a very thin, even monomolecular, layer on the surface of the support. (b) The greater the surface area of the catalyst, the more reaction sites, and the greater the rate of the catalyzed reaction. 14.77 As illustrated in Figure 14.21, the two C–H bonds that exist on each carbon of the ethylene molecule before adsorption are retained in the process in which a D atom is added to each C (assuming we use D2 rather than H2). To put two deuteriums on a single carbon, it is necessary that one of the already existing C–H bonds in ethylene be broken while the molecule is adsorbed, so the H atom moves off as an adsorbed atom, and is replaced by a D. This requires a larger activation energy than simply adsorbing C2H4 and adding one D atom to each carbon. 14.79 (a) Living organisms operate efficiently in a very narrow temperature range; heating to increase reaction rate is not an option. Therefore, the role of enzymes as homogeneous catalysts that speed up desirable reactions without heating and undesirable side-effects is crucial for biological systems. (b) catalase: 2H2O2 → 2H2O + O2; nitrogenase: N2 → 2NH3 (nitrogen fixation) 14.81 Analyze/Plan. Let k = the rate constant for the uncatalyzed reaction, kc = the rate constant for the catalyzed reaction According to Equation [14.20], ln k = –Ea /RT + ln A Subtracting ln k from ln kc, 388 14 Chemical Kinetics (a) Solutions to Exercises RT = 8.314 J/K-mol × 298 K × 1 kJ/1000 J = 2.478 kJ/mol; ln A is the same for both reactions. The catalyzed reaction is approximately 10,000,000 (ten million) times faster at 25°C. (b) RT = 8.314 J/K - mol × 398 K × 1 kJ/1000 J = 3.309 kJ/mol The catalyzed reaction is 200,000 times faster at 125°C. Additional Exercises 14.83 A balanced chemical equation shows the overall, net change of a chemical reaction. Most reactions occur as a series of (elementary) steps. The rate law contains only those reactants that form the transition state of the rate-determining step. If a reaction occurs in a single step, the rate law can be written directly from the balanced equation for the step. 14.86 (a) 2– The rate increases by a factor of nine when [C2O4 ] triples (compare experiments 1 and 2). The rate doubles when [HgCl2] doubles (compare experiments 2 and 3). 2– 2 The rate law is apparently: rate = k[HgCl2][C2O4 ] (b) 14.89 14.92 Using the data for Experiment 1, –3 –2 –1 2 –5 (c) rate = (8.672 × 10 M s )(0.100 M)(0.25 M) = 5.4 × 10 M/s (a) t1/2 = 0.693/k = 0.693/7.0 × 10 s = 990 = 9.9 × 10 s (b) k= (a) A = abc, Equation [14.5]. A = 0.605, a = 5.60 × 10 cm M , b = 1.00 cm (b) Calculate [c]t using Beer’s law. We calculated [c]0 in part (a). Use Equation [14.13] to calculate k. –4 –1 2 –4 –1 = 2.05 × 10 s 3 –4 –5 –1 –1 –4 –4 k = ln(1.080 × 10 ) – ln(4.464 × 10 ) / 1800 s = 4.910 × 10 = 4.91 × 10 s (c) For a first order reaction, t1/2 = 0.693/k. 389 –1 14 Chemical Kinetics Solutions to Exercises –4 –1 3 3 t1/2 = 0.693/4.910 × 10 s = 1.411 × 10 = 1.41 × 10 s = 23.5 min (d) At = 0.100; calculate ct using Beer’s law, then t from the first order integrated rate equation. 3 3 t = 3.666 × 10 = 3.67 × 10 s = 61.1 min 14.95 ln k 1/T –24.17 3.33 × 10 –20.72 3.13 × 10 –17.32 2.94 × 10 –15.24 2.82 × 10 –3 –3 –3 –3 4 The calculated slope is –1.751 × 10 . The activation energy Ea, equals – (slope) × (8.314 J/mol). Thus, 4 5 Ea = 1.8 × 10 (8.314) = 1.5 × 10 J/mol 2 = 1.5 × 10 kJ/mol. (The best-fit slope 4 4 is –1.76 × 10 = –1.8 × 10 and the val2 ue of Ea is 1.5 × 10 kJ/mol.) 14.99 (a) Cl2(g) 2Cl(g) (b) Cl(g), CCl3(g) (c) Reaction 1 - unimolecular, Reaction 2 - bimolecular, Reaction 3 - bimolecular (d) Reaction 2, the slow step, is rate determining. (e) If Reaction 2 is rate determining, rate = k2[CHCl3][Cl]. Cl is an intermediate formed in reaction 1, an equilibrium. By definition, the rates of the forward and 2 reverse processes are equal; k1 [Cl2] = k –1 [Cl] . Solving for [Cl] in terms of [Cl2], Substituting into the overall rate law (The overall order is 3/2.) 390 14 Chemical Kinetics 14.101 Solutions to Exercises Enzyme: carbonic anhydrase; substrate: carbonic acid (H2CO3); turnover number: 7 1 × 10 molecules/s. Integrative Exercises 14.104 –5 Analyze/Plan. 2N2O5 → 4NO2 + O2 –1 rate = k[N2O5] = 1.0 × 10 s [N2O5] Use the integrated rate law for a first-order reaction, Equation [14.13], to calculate k[N2O5] at 20.0 hr. Build a stoichiometry table to determine mol O2 produced in 20.0 hr. Assuming that O2(g) is insoluble in chloroform, calculate the pressure of O2 in the 10.0 L container. Solve. ln[A]t – ln[A]0 = –kt; ln [N2O5]t = –kt + ln [N2O5]0 –5 –1 4 ln [N2O5]t = –1.0 × 10 s (7.20 × 10 s) + ln(0.600) = –0.720 – 0.511 = –1.231 [N2O5]t = e –1.231 = 0.292 M N2O5 was present initially as 1.00 L of 0.600 M solution. mol N2O5 = M × L = 0.600 mol N2O5 initial, 0.292 mol N2O5 at 20.0 hr 2N2O5 t=0 → 4NO2 + O2 0.600 mol 0 0 change –0.308 mol 0.616 mol 0.154 mol t = 20 hr 0.292 mol 0.616 mol 0.154 mol [Note that the reaction stoichiometry is applied to the ‘change’ line.] PV = nRT; P = nRT/V; V = 10.0 L, T = 45°C = 318 K, n = 0.154 mol 14.106 (a) Use an apparatus such as the one pictured in Figure 10.3 (an open-end manometer), a clock, a ruler and a constant temperature bath. Since P = (n/V)RT, ΔP/Δt at constant temperature is an acceptable measure of reaction rate. Load the flask with HCl(aq) and read the height of the Hg in both arms of the manometer. Quickly add Zn(s) to the flask and record time = 0 when the Zn(s) contacts the acid. Record the height of the Hg in one arm of the manometer at convenient time intervals such as 5 sec. (The decrease in the short arm will be the same as the increase in the tall arm). Calculate the pressure of H2(g) at each time. (b) Keep the amount of Zn(s) constant and vary the concentration of HCl(aq) to de+ – termine the reaction order for H and Cl . Keep the concentration of HCl(aq) constant and vary the amount of Zn(s) to determine the order for Zn(s). Combine this information to write the rate law. (c) –Δ[H ]/2Δt = Δ[H2]/Δt; –Δ[H ]/Δt = 2Δ[H2]/Δt + + 391 14 Chemical Kinetics Solutions to Exercises [H2] = mol H2/L H2 = n/V; [H2] = P (in atm)/RT + Then, the rate of disappearance of H is twice the rate of appearance of H2(g). 14.109 (d) By changing the temperature of the constant temperature bath, measure the rate data at several (at least three) temperatures and calculate the rate constant k at these temperatures. Plot ln k vs 1/T. The slope of the line is –Ea/R and Ea = –slope (R). (e) Measure rate data at constant temperature, HCl concentration and mass of Zn(s), varying only the form of the Zn(s). Compare the rate of reaction for metal strips and granules. In the lock and key model of enzyme action, the active site is the specific location in the enzyme where reaction takes place. The precise geometry (size and shape) of the active site both accommodates and activates the substrate (reactant). Proteins are large biopolymers, with the same structural flexibility as synthetic polymers (Chapter 12). The three-dimensional shape of the protein in solution, including the geometry of the active site, is determined by many intermolecular forces of varying strengths. Changes in temperature change the kinetic energy of the various groups on the enzyme and their tendency to form intermolecular associations or break free from them. Thus, changing the temperature changes the overall shape of the protein and specifically the shape of the active site. At the operating temperature of the enzyme, the competition between kinetic energy driving groups apart and intermolecular attraction pulling them together forms an active site that is optimum for a specific substrate. At temperatures above the temperature of maximum activity, sufficient kinetic energy has been imparted so that the forces driving groups apart win the competition, and the threedimensional structure of the enzyme is destroyed. This is the process of denaturation. The activity of the enzyme is destroyed because the active site has collapsed. The protein or enzyme is denatured, because it is no longer capable of its “natural” activity. Cl• + Cl• → Cl2 is a termination step. 392